Last week was big, very big, for news about the science of memory.

First, researchers in the MIT lab of Nobel Prize winner Susumu Tonegawa were able to change an unpleasant memory to an enjoyable one. The study was in mice, the research technique is physically invasive, and the mice were GMOs. So the results are not directly applicable to human memories. But the work makes it possible believe that someday there will be a cure for post-traumatic stress disorder and treatments that can wipe out traumatic memories that are wrecking people’s lives.

The other noteworthy new report does apply directly to people, and it’s not decades away, either. Researchers have improved memory by zapping people’s brains with weak pulses of electromagnetic energy. It wasn’t a big gain in memory, and it lasted no more than 24 hours. But this work has potential for treating dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease), brain injury, stroke, and other conditions involving memory loss. The researchers, based at Northwestern, employed transcranial magnetic stimulation, which has been around for a while. In TMS, the researchers use a magnet to activate specific parts of the brain for study.

I won’t describe the research in detail because I want to raise here some worries about a related topic: the implications, ethical and otherwise, of altering memories. Descriptions of both studies are available in many news stories. Not all the articles describing the very complex mouse work were illuminating, as Faye Flam noted at the Knight Science Journalism Tracker; the Tracker is an MIT-based blog that evaluates science journalism (and is, unfortunately, about to go out of business.) Here’s a piece on the mouse study that Flam particularly recommends, an open-access story at Science by Emily Underwood.

For details on the human TMS study, consult Virginia Hughes’s blog Only Human at National Geographic. Susannah Locke described the human study too, in a Vox post that is also an explainer about memory and memory enhancement.

Even the head of the National Institute of Mental Health, who is on top of everything brainy, is a bit awed by these two papers. Last Thursday Thomas Insel blogged that this research “may be moving the study of memory into a brave new world, where we can not only monitor memory but manipulate it.” He noted, “the introduction of neurotechnologies that can target specific memories by tuning brain circuits takes us into a new era in the study of memory.”

And that’s not just hype. He also notes that, while we already possess techniques that can alter memory, such as psychotherapy, doing it with neurotechnology “raises thorny ethical issues.”

Transcranial magnetic stimulation: Some thorny ethical issues

The good news about the idea of TMS for memory enhancement is that it’s applied to quite specific brain regions, whereas drugs taken for enhancement — college students popping ritalin, for instance — flood the entire brain and body. On the other hand, although TMS has been around for a while, and the FDA has even approved it for treating depression, its long-term effects are unknown.

If TMS does turn out to improve memory, it will prompt the same kind of questions as drugs for improving performance in sports. What’s legitimate? Is enhancement unfair to other competitors who don’t enhance? If all of the players do it, is it unfair and dishonest to the audience? Does it make the idea of top performance meaningless? What about the health consequences? What about questions of justice: with TMS in particular, treatments would probably be costly and available most easily to people who already possess many advantages. Why shouldn’t everybody have access to them?

Whether future studies confirm that TMS improves memory or not, it already has produced a problem: Do-it-yourself electrical stimulation of the brain. People are building TMS equipment with parts from Radio Shack. An Atlanta doc charges $2400 for a TMS kit and training for DIY zapping, Greg Miller reports for Wired. Companies are selling DIY TMS equipment. At least one of them promotes it to enhance video gaming performance so that the company can avoid having to get medical device approval from the FDA.

All this amateur enthusiasm has taken off despite the fact that TMS is not yet proven. One British researcher reports that he has been unable to repeat a “successful” TMS experiment he published himself, and he has savaged the methodology he and other researchers have employed. There are known risks to TMS, like seizures. Particularly worrisome is the use of DIY TMS by the young, whose brains are still growing. Researchers at Oxford have called recently for regulation of commercial DIY TMS providers.

Changing memories: Some thorny ethical issues

We have long known that memory is unreliable and that eyewitness accounts of an event can be untrustworthy. But the ability to alter memories deliberately could have profound impacts, for instance on law enforcement, the legal system, maybe on national security. Not to mention personal relationships.

Bioethicist Arthur Caplan (Disclosure: a former colleague at the Hastings Center) has argued that changing memories could be worth it if the changes enabled someone who is a prisoner of an awful memory to function. No argument there, at least in principle.

On the other hand, we don’t even know, at this point, whether memories can be separated from each other. Maybe altering a particular memory will have unpredictable ripple effects on other memories. That seems plausible, since memories are linked to each other in the brain.

Each of us is, in a sense, the sum of our memories. If my memories are changed in specific ways with the help of technology, do I become a different person? Does the idea of an accurate memory, already a bit shaky, cease to have any meaning at all?

What, in fact, is reality? In part, at least, reality is memories. And maybe they don’t have to be real memories.

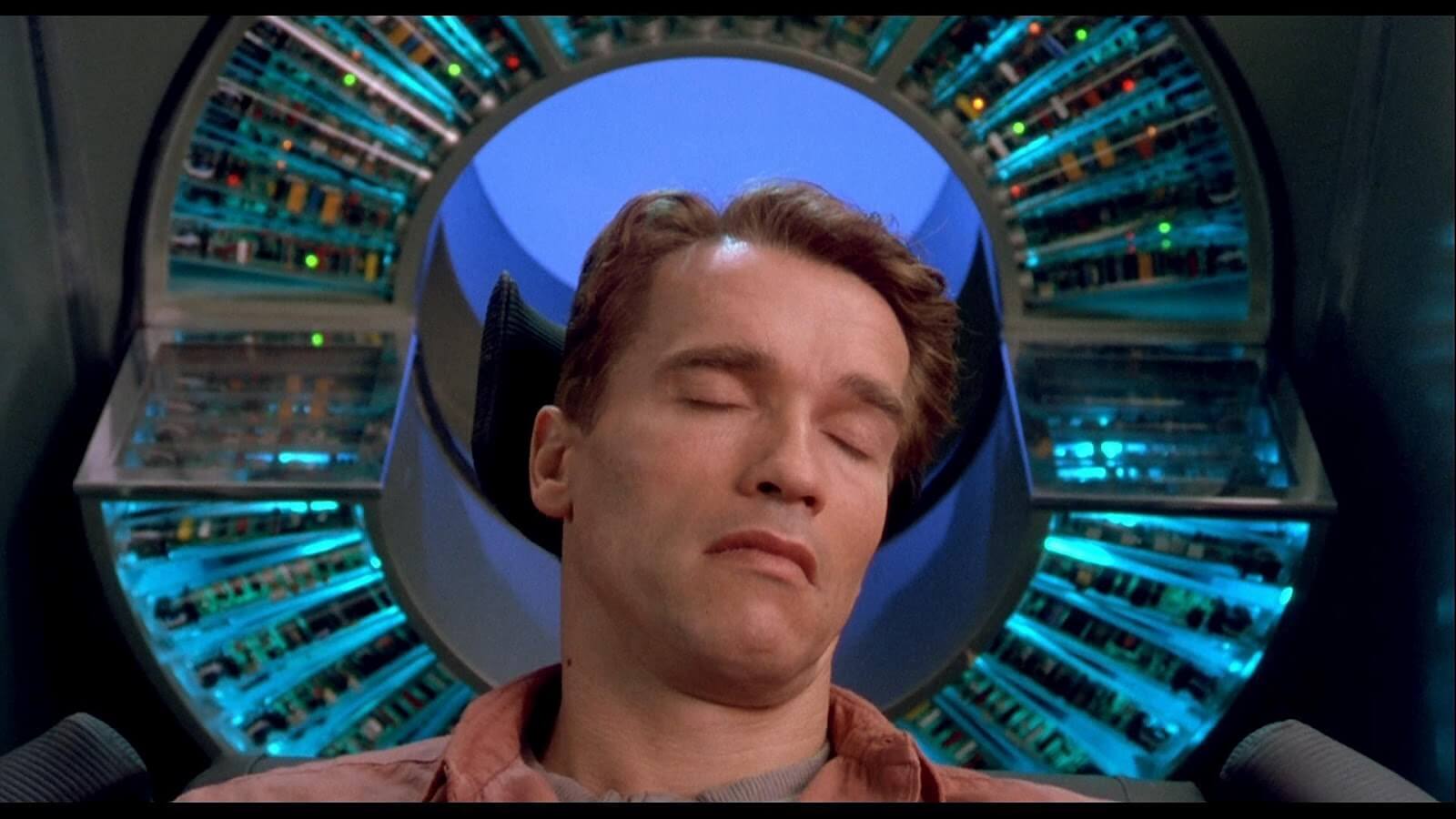

This idea was fun in the movie Total Recall (the 1990 original, with Sharon Stone and what’s-his-name, the former governor of some western state, not the even more incoherent recent remake.) I suspect it would be messy and scary and sometimes appalling in real life. If we even knew what real life was anymore.

Tabitha M. Powledge is a long-time science journalist and a contributing columnist for the Genetic Literacy Project. She also writes On Science Blogs for the PLOS Blogs Network. Follow her @tamfecit