In 1983, Margaret Heckler, then the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services made a proclamation that a vaccine for HIV would be ready in two years. She couldn’t have been further from the truth. It’s been three decades since and the search for a vaccine continues has proven to be elusive.

While there have been many attempts –several clinical trials conducted in the last decade, none of them have shown any positive results that be translated to the clinic, except for one study in Thailand conducted in 2009. That too was only moderately effective, helping reduce the risk of infection by 31 percent.

What has been even more frustrating is the fact that two major trials, considered promising at first, were shut down because the data showed the vaccine increased the risk of an infection among study participants. A third large trial was closed down in 2013 barely a month after the study reached its enrollment goals because an analysis of the preliminary data showed that the vaccine offered neither protection from infection nor reduced the severity of the disease. Though not statistically significant, the data also suggested that participants who received the vaccine may have had an increased risk of infection.

What is behind the puzzling increase in risk of infection from the vaccinations? The answer as it turns out might have a lot to do with how HIV has evolved to become one of the smartest viruses around.

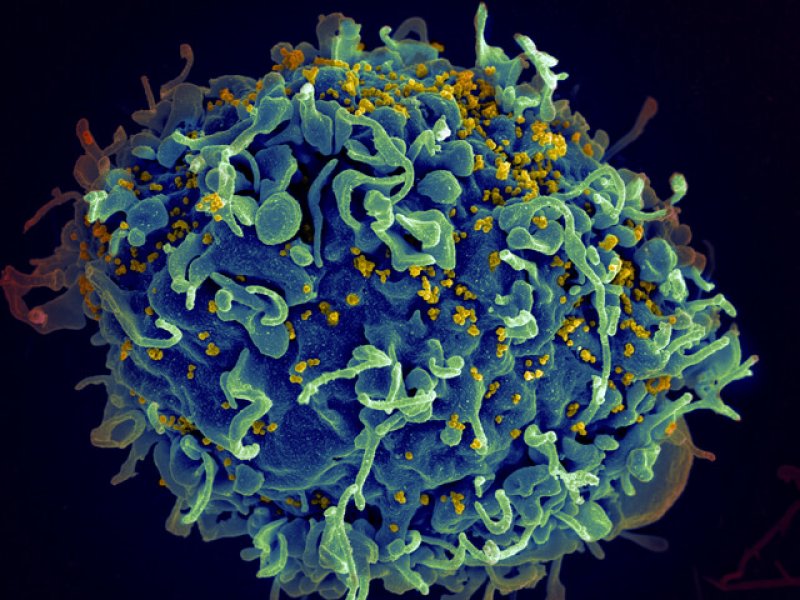

Immune cells known as T-cells are one of the ways by which our body fights off viral infections. There are two major kinds of T-cells, ‘helper’ T cells, also known as CD4+ T cells and killer T cells also known as CD8+ T cells. Killer T cells as the name suggests are important in removing infected cells from the body while the CD4+ helper T cells help in recognizing the virus from the proteins that make up its envelope and activate other cells of the immune system including killer T cells. And the trick HIV has come up with to outsmart this system is to infect the very cells that are supposed to defend the body against it, the CD4+ helper T cells.

Now in a recent study, researchers have uncovered some clues as to how experimental HIV vaccines may set up the immune system, making it easier for HIV to infect the body later.

Using a macaque monkeys as model systems, researchers tested several vaccine candidates to the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV), the monkey analog of HIV. Upon infecting the animals with SIV they found that vaccines did not protect the monkeys against infection. Additionally, they also found that animals that were vaccinated were more susceptible to infection when compared to the non-immunized control animals. This was not an unexpected finding given the results from the clinical trials and previous research conducted in monkeys.

But in this case, the team identified a potential cause, noting increased levels of CD4 helper T cells in the skin layer lining the rectum, a common point of virus entry into the body. Since the CD4 cells are targets for the virus, this might explain why vaccinated animals had a higher susceptibility to SIV. While this does not mean that the human vaccine trials backfired for the same reasons, it does provide an important clue to solving a puzzling problem.

The study differed slightly from other studies in that the vaccines that they used did not contain pieces of the viral envelope protein which would elicit the production of antibodies against the virus. This ‘reductionist approach’, while differing from the traditional vaccines, allowed the researchers to focus specifically on how helper and killer T cells responded to the vaccines and SIV infection and may have helped to uncover the findings in the study.

HIV is not the only virus that we’ve found it difficult to create a vaccine against though. The other never-ending fight that we have been having on an annual basis every flu season is with the influenza virus. Similar to the HIV, it has an extraordinary high mutation rate, constantly altering proteins that coat the virus. Thus any vaccine that we create has only a partial chance at being effective. This year’s vaccine for example is even less effective than we had originally hoped, because the virus mutated after the vaccine was produced. However, we are making progress on that front as well, with a ‘universal’ flu vaccine that would offer long term protection expected to undergo clinical trials this year.

As for the HIV, we now have one more nugget of information in the race to design an effective vaccine. This time it’s about how not to inadvertently give the virus an upper hand.

Arvind Suresh is a science communicator and a former laboratory biologist. Follow him @suresh_arvind

Additional Resources

- Cure for HIV? New gene-editing technique shows promise, Genetic Literacy Project

- HIV’s slow evolution in humans would not affect vaccine development, Health Site

- Researchers hammering away at a chink in HIV’s armor, Scientist