As lockdown continued, I found thousands of dance videos online, favoring a blond woman instructor from Germany and groups of teens from the Philippines and South Korea. It felt worldly while being trapped. My local Zumba instructors quickly reinvented themselves for zooming. Then when the world started to open up again, I returned to classes, masked until that, too, was dropped.

The one thing that stood out, especially during COVID, was how few men participated. Part of the reason may be a reaction to what some may have felt was a ‘girly’ exercise. But is something else going on here?

Origins of Zumba – Not Jane Fonda nor Richard Simmons

According to lore, Zumba is the brainchild of Colombian choreographer Beto Pérez. In the 1990s Beto, as my instructors reverently call him, supposedly forgot his music one day and substituted tapes of merengue and salsa, which are dances (not foods). Soon, Beto started adding the songs to other classes.

Like tiny mammals evolving beneath the footsteps of the dinosaur giants, the dance evolved, officially debuting in fitness videos in 2001. Beto at first named the new routines rumbacize, then sumba, but ended up with Zumba, reportedly because as a kid he’d loved Zorro.

I tried Zumba when it began, but didn’t stick with it because it was very fast and the music unfamiliar. I restarted about ten years ago and found that, again like the mammals, it had diversified. Today a class might include Uptown Funk, Dancing Queen, Night Fever, the latest from Ed Sheeran or Meghan Trainor, and also the Latin-inspired pieces that I’ve come to love. They send my step counter soaring.

Even though a male of the species invented Zumba, in my experience men rarely participate, the near-absence of folks with Y chromosomes starkly apparent. They either don’t want to do it, or can’t. My classes have zero or one man, amidst at least two dozen women.

The men who go to Zumba have guts, and some apparently have something called “beat deafness,” which is “a form of congenital amusia.” They generally lack rhythm, memory, or any inkling of where their bodies are in three-dimensional space, a characteristic called proprioception. Their vestibular sense is out-of-whack, their eyes and ears unable to communicate via nerves with their muscles, tendons, and joints. It’s a perpetual and pervasive disconnect that just this morning sent the hapless male gesticulating next to me repeatedly in the wrong direction.

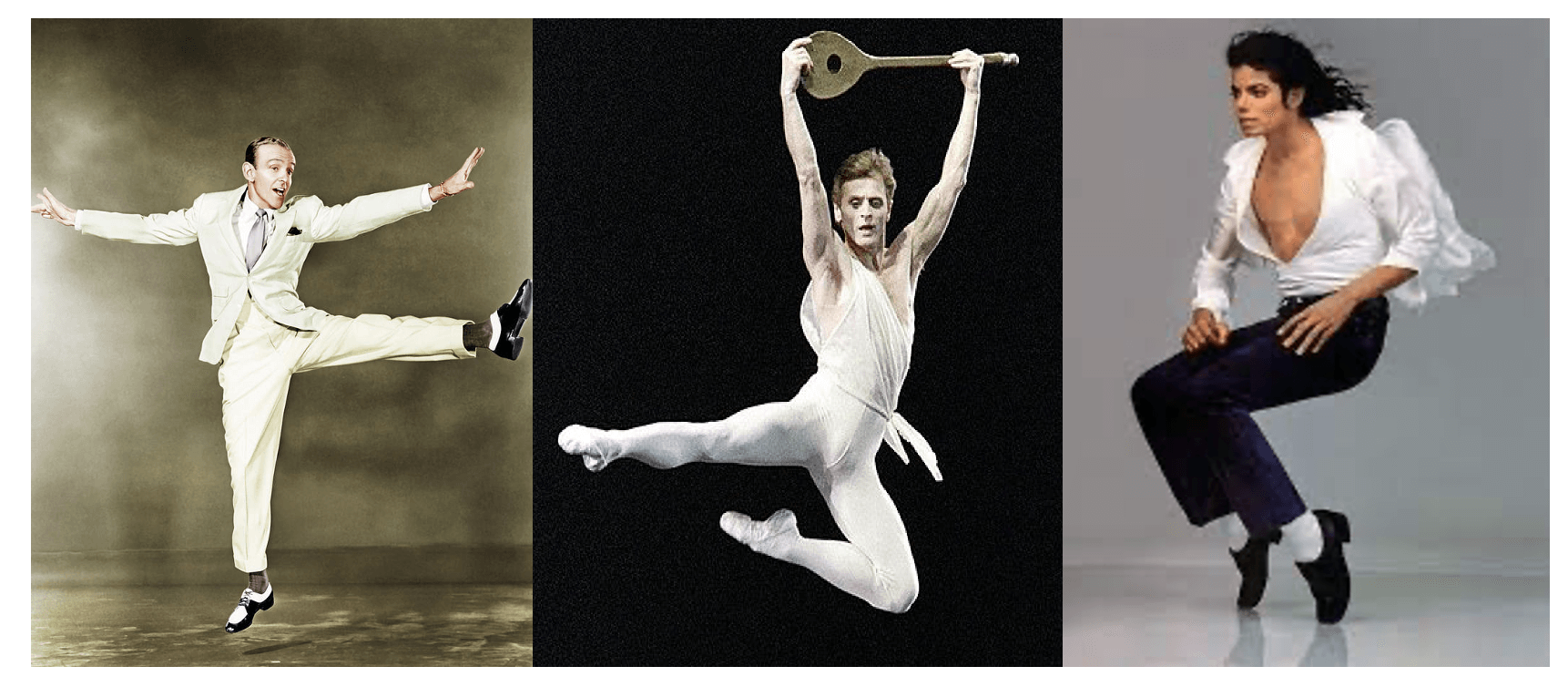

Male dance GOATs

Some research, although it’s not formal, suggests that men and women process sounds differently, and males are more likely than women to suffer from an inability to dance. Not all men are so afflicted; from Fred Astaire to Mikhail Baryshnikov to Michael Jackson, more than a few humans with the Y chromosome have demonstrated their chops on the dance floor.

Zumba though — that’s a different story.

Shortly after Zumba classes resumed as COVID ebbed, a man gamely joined our class. A gregarious fellow, he happily introduced himself as a pickleball champ, his attire more suited to chasing balls than rhythmic movement. He tried. He lasted longer than any other male I’ve watched, about four weeks. He’s back on the pickleball court (something I have zero talent for).

Of course, there are exceptions. John Travolta would undoubtedly be great. My Zumba instructor Carolyn brings her husband Ronnie to class, and he’s a terrific dancer – but maybe that’s what attracted them to each other in the first place. Ronnie not only keeps up with Carolyn, but sometimes he leads the class. And he has only one lung!

I couldn’t drag my husband to Zumba, but he did try aerobics. It didn’t go well.

Aerobics is several orders of magnitude easier than Zumba, consisting of stepping side-to-side, front-to-back, marching, and an occasional V step, which is what it sounds like. Larry perpetually moved in the wrong direction, unable to handle even the rudiments, and couldn’t leave fast enough. However, he’s run more than a dozen marathons. His talents clearly lie elsewhere.

This week, a new male showed up to Zumba, next to me. His primary limitation seemed to be processing speed, rendering him unable to keep up, but I had that problem too at first. The trick is to feel the beat, the music. When we had to take 8 slides to the right, I careened right into him because he was standing still, befuddled. I felt badly for him, but he gave me the idea to write this article.

The approach to getting the most out of Zumba is to perceive the patterns, the repetitions, so you can sense what’s coming. Most dances are just 3 or 4 short routines, repeated 3 or 4 times. I wonder why I’m adept at learning that, but was completely flummoxed in college by organic chemistry, which is also based on pattern recognition. Perhaps it is the camaraderie of an exercise class compared to competing against pre-meds thinking they’re in the Hunger Games while taking orgo.

Anyway, I started to wonder about the biology of the ability to do Zumba, and the contribution of genetics. Wouldn’t natural selection have favored inherited traits that enabled a human body to deftly catapult away from danger, like a saber-toothed tiger or an avalanche?

Diving into the data

To identify genes that might have variants conferring the ability to dance, one might peruse the genetic markers (single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs) that consumer DNA testing companies use to tell consumers about themselves. Perhaps 23andMe already probes dancing ability? So I decided to look, and found three references.

1. 23andMe

While 23andme tests spit samples for gene variants associated with such scintillating traits as dandruff, cleft chin, ability to match musical pitch, mosquito bite frequency, preferring chocolate to vanilla, and hating the sounds of someone chewing, I found only one that might facilitate the ability to dance, described in this blog post from 2008. It reports on an extra bit at the start of a gene called AVPR1a that in voles – a type of rodent – is associated with social bonding and in college students with tendency to give away money playing the Dictator Game. A 2007 article mentioned in the blog links the AVPR1a variant to “creative dance performance,” which sounds more complex than Zumba, but possibly related.

2. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

This is a database that serves as the bible of clinical geneticists. I found aptitude for spatial visualization arising from a gene located towards the tip of the short arm of the X chromosome. That would be consistent with females having two X chromosomes to the male’s one. Although a process called X inactivation turns off one X in each female cell to compensate for her genetic superiority – it’s actually called “dosage compensation” – statistically some women would express more than half of their X chromosomes. Perhaps they’re the dancers.

3. Meta analysis

This study of nearly 4,000 papers, from four male researchers, sought genes that have variants that might affect dancing ability. The findings, published in PLoS One in 2021, analyzed three traits: cardiovascular fitness, muscular strength, and anaerobic power. Those skills aren’t the same as the ability to remember a pattern of three cha-chas, two salsas, four Charlestons and a grapevine, but maybe some of the same genes are involved.

Being a study of studies, the meta-analysis spewed data. The conclusion:

Subgroup analysis showed 44%, 72% and 10% of the response variance in aerobic, strength and power phenotypes, respectively, were explained by genetic influences.

I perused the table of implicated genes and considered what the proteins they encode do. Mostly, they make sense for dancing ability.

A familiar gene is ACTN3 (alpha-actinin-3). The protein is well known for its two forms, one that predominates among sprinters and the other among long-distance runners. Another is APOE, a protein that binds fats. Variants lie behind Alzheimer’s and cardiovascular disease.

Several genes – COXIV, CS, HADH, and PFK – encode proteins that take part in the Krebs cycle, which may elicit flashbacks to high school biology. A gene called AMPK encodes a protein kinase, which senses ATP (cellular energy) level. PGC encodes a digestive enzyme. These are all players in cellular respiration, which is the extraction of energy from food. So they could be important in the ability to power through a Zumba class.

One puzzling identified gene is ACE2, which encodes angiotensin converting enzyme 2. ACE2 regulates kidney and heart health – and it’s also the receptor for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID. But ACE2 is on so many types of cells that it might just show up anywhere.

I was happy to find these references, but none of the implicated genes elucidates how and why the men I’ve observed attempting Zumba cannot seem to follow simple instructions, remember anything, or assign movements to beats. So I propose a more direct study.

Use the 23andMe data – let’s say a million SNPs. Divvy up participants by gender and whether or not they regularly do Zumba. Have them self-report mastery level. I’d give myself an 8, my instructors 10s, the man who crashed into me this morning a 4. Which gene variants do the 10s share? Compare that to a large sample of sedentary individuals of both sexes, and perhaps include those who do not identify as a binary gender choice.

If the analysis points to a specific gene that has variants that regularly show up in dancers but not in those who can’t dance, then perhaps there’s a genetic component to the ability to do Zumba.

Ricki Lewis has a PhD in genetics and is a science writer and author of several human genetics books. She is an adjunct professor for the Alden March Bioethics Institute at Albany Medical College. Follow her at her website or Twitter @rickilewis