The war between science and anti-crop biotechnology advocacy groups has escalated since the summer release of the European Commission Report advocating for the deregulation of gene-editing and other new genetic breeding techniques (NGTs).

Scientists around the world, and even across Europe almost universally embrace these advances while many environmental groups long opposed to the genetic tinkering of crops have escalated their lobbying efforts in an attempt to scuttle the reforms.

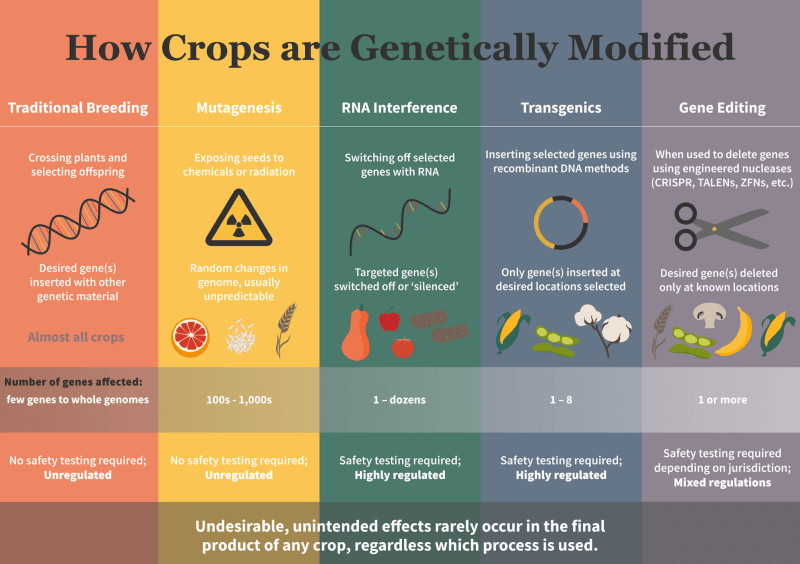

The recommendations apply only to new techniques, most developed over the past decade. Genetically modified transgenic crops (GMOs) would continue to be strictly regulated based on concerns that transgenics, or moving genes from one species to another, could cause health damage— a view not supported by 30+ years of usage globally and thousands of studies. These new techniques involve tinkering with plant genomes in ways similar to how mutations naturally occur.

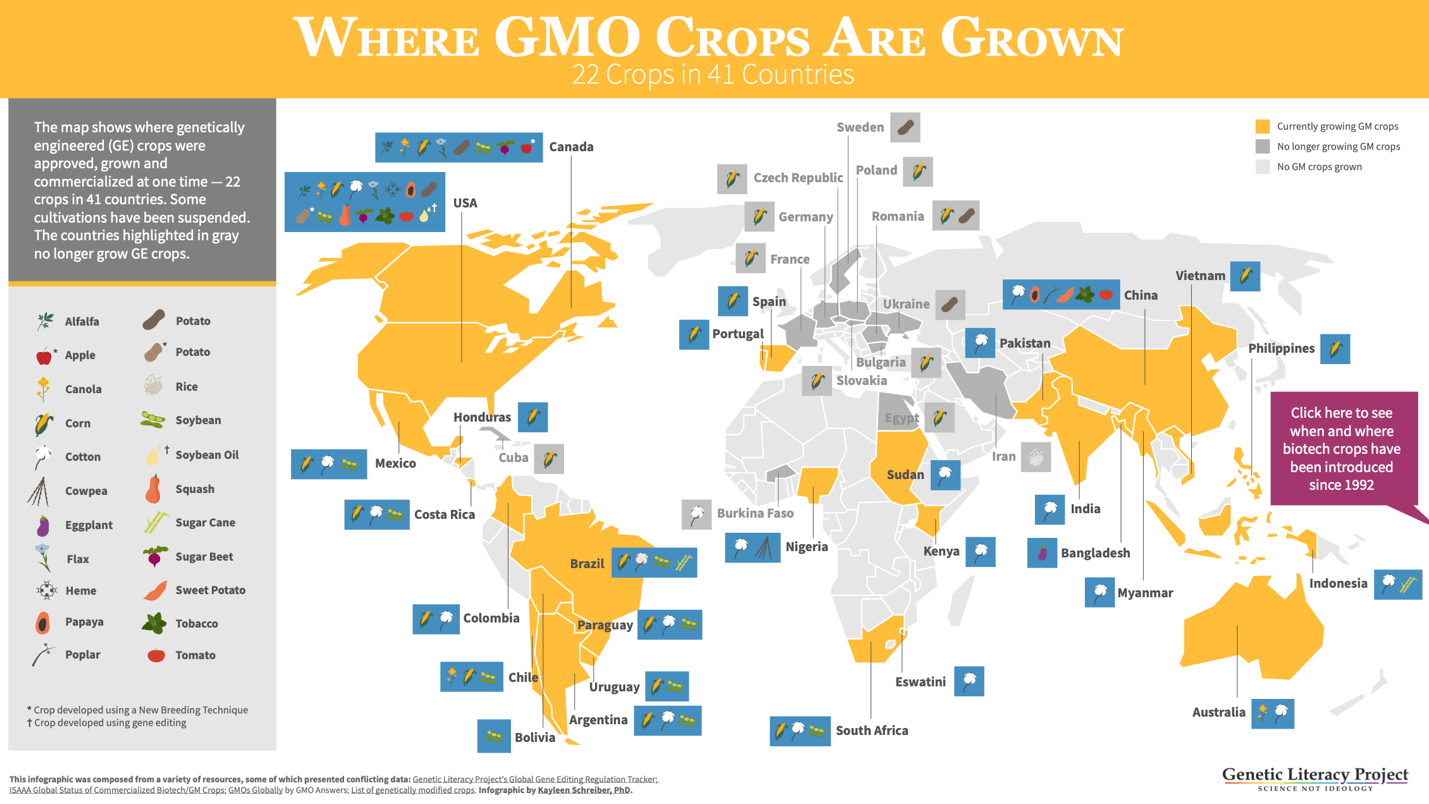

Ironically, and regardless of whether these recommendations are adopted, the EU will remain the largest global importer of GMOs. It annually imported tens of millions of tons of genetically modified corn, soybeans and rapeseed to feed their livestock. The only two EU countries that do grow GMO food grain — Spain and Portugal — have been winding down their already minimal production in recent years.

The current critics of second-generation genetically engineered crops are the usual suspects, beginning with the organic industry. IFOAM Organics International, which promotes the interests of its industry, said it viewed the exemption of certain NGTs from risk assessment, traceability and labelling as a “denial of the precautionary principle and a step backward for biosafety and consumer information.”

Environmental advocacy groups have long considered the genetic engineering of crops a defining issue. Since the 1990s, Greenpeace has muddied the science, tarring GMOs as genetic freaks. Now they label NGTs as a “Frankenstein” experiment that “disregards safety and consumer rights.”

Greenpeace is not alone among technology-skeptical NGOs. According to Mute Schimpf, food campaigner at Friends of the Earth Europe, NGTs “are no more than untested new GMOs” peddled by greedy companies.

The European Commission is choosing to give in to a long-lasting campaign from big corporations instead of protecting citizens’ rights,” he said. “It’s appalling to see that the Commission basically says agribusiness do not need to bear the risks of releasing untested new GMOs into our fields and plates, but consumers, farmers and nature do.

In total, forty-six NGOs supported a public petition opposing any changes in the EU precautionary regulations, writing:

The EU Commission is planning to soften EU genetic engineering law. There is a threat of deregulation and thus a free pass for genetically modified plants. Not with us! … [W]e have therefore started a new petition and demand that regulation be maintained even for new genetic engineering. This includes: Labeling, risk assessment, authorization, traceability, transparency, monitoring and liability. … Not behind our backs — No free pass for new genetic engineering in our food.

Enviro-activists evolve into science rejectionists

From the vehemence of these attacks, one might assume that “new GMOs” (aka CRISPR et al) have the potential to destroy humankind and are a greater threat than climate change or the potential for global war. But their inflammatory rhetoric does not square with the facts. Genetically modified (transgenic) seeds have been successfully grown by dozens of countries since the 1990s without evidence of hazard to human and animal health or to the environment.

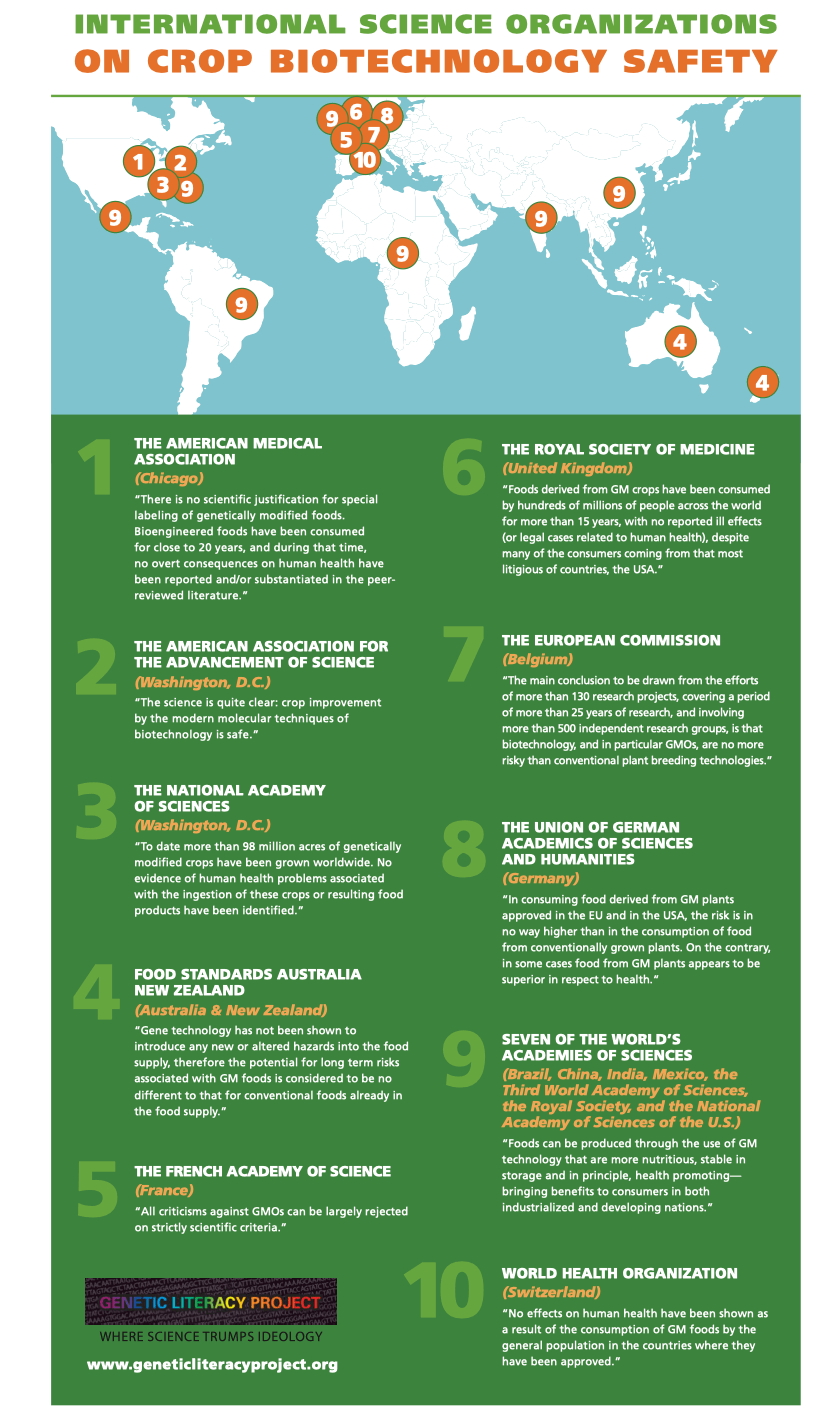

There is an overwhelming scientific consensus that GMO crops are just as safe and sustainable as conventionally and organically grown foods and that they present no unique environmental hazards. Almost 300 global science organizations support that position, including all of the major National Academies of Science.

There are shelves full of about-to-be-introduced GE crops that could increase farmer productivity and reduce disease, insect, stress, and drought vulnerabilities — challenges that farmers limited to strict organic practices developed many decades ago are not technologically equipped to address.

Anti- GE campaigners like to present themselves to the public as eco-warriors engaged in a titanic David and Goliath battle against Big Ag which has corrupted science and government agencies to bolster their profits at the expense of the environment and human health. They have been very successful in embedding this view among the public which is generally antagonistic to the technology.

What started in the 1990s as skepticism about the technology has evolved into a religious-like fealty to ‘naturalism’. But that ideological predisposition ignores the fact that humans have been transforming almost every vegetable, fruit and grain since the dawn of humankind.

“There is no such thing as a ‘natural ecosystem’”, says Maarten Chrispeels, a plant biologist at the University of San Diego:

An agricultural landscape may look attractive – a vineyard in the San Diego backcountry for example, or a sunflower field in full bloom in the Provence in France – but its creation required the complete destruction of the natural ecosystem and its replacement by an agricultural ecosystem. Further, to grow so many of the same plants in one field while at the same time suppressing the growth of other plants – in this case, weeds – is not natural.

Anti-GE campaigners like to pretend that the use of biotechnology is new, that we need to be cautious because we do not understand how the engineered crops could ultimately impact humans and the environment. But the reality is that humans have been genetically modifying crops in one form or another for thousands of years in search of desired traits.

“Our crop plants were domesticated 5,000 to 10,000 years ago, and in the process, their genetic makeup was changed considerably and irreversibly,” Professor Chrispeels adds. “It’s changed so much in fact that crop plants generally cannot survive in nature.

To illustrate that point, this chart outlines the different types of breeding techniques that humans have used over the centuries, and how many genes are modified in that process:

Food crops have been developed by genetic engineering via processes of selective breeding, hybridization, grafting, mutagenesis, inbreeding and molecular marker assistance among others. Without such ‘unnatural’ techniques we would not have the wide variety of foods we have today, crops would not be as tasty and nutritious, and yields would be lower. Here are some examples of crops that are often sold today as ‘natural’ and organic.

- Seedless watermelons, oranges and grapes were crossbred more than 50 years ago. In the case of watermelons, the male pollen containing 22 chromosomes is crossed with the female watermelon flower, which has been chemically altered to contain 44 chromosomes. That doesn’t seem very natural.

- Tangelos, peacharines, plumcots, papples (cross between and apple and a pear), blood limes, pineberries and tayberries were never found ‘in nature.’

- Broccoli, a cruciferous vegetable, along with its genetic cousins—cabbage, kale, cauliflower, and Brussels sprouts—were created by humans over the last two thousand years from a weed.

- Cherry tomatoes were created via a twelve-year breeding program that manipulated the genes of a wild Peruvian tomato species.

- The corn we eat today does not bare any resemblance to the original corn native to Mexico because of selective breeding.

- In a process called mutagenesis, more than 3000 plants including sweet Ruby Red grapefruits and types of organic-quality Italian wheat were created by bombarding seeds with radiations until they randomly yielded a new trait.

Gene-editing techniques can speed up these kinds of beneficial changes and at a tiny fraction of the cost of conventional breeding techniques. ironically this next generation of genetic engineering could help break what activists claim is a ‘stranglehold” by multi-national corporations over global agriculture.

Consequences of rejectionism

If anti-GE campaigners in the EU find a way to block the introduction of GE crops, it would seriously damage European farmers and place them at a severe global competitive disadvantage. It would result in reduced farm productivity and profitability, and an increase in the cost of food to EU consumers.

One example should suffice to highlight this disadvantage. It is likely that within the next ten years many crops will be genetically engineered to be disease resistant thus saving farmers throughout the world billions of dollars in crop losses and the cost of spraying synthetic crop control chemicals to control diseases. Food prices in the EU would likely soar while food costs in the rest of the world would decrease, all while food quality increases.

We’ve learned a hard lesson over the past few years as climate change has disrupted farming and food: We need more resilient crops. Over the past few summers, Europe has been hard hit by drought and heat waves.

“Brown is the color of summer in northern Europe this year,” noted one commentary.

Fields that are usually covered in lush green grass have now turned to dust, trees are shedding their leaves and animals eating dry hay or grain instead of grazing in pastures. Farmers in around a dozen countries — from Ireland to the Baltics — are grappling with a once-in-a-generation drought. The unrelenting heat wave has devastated crops, with more than half of the harvest expected to be lost in some areas.

What happens when climatic catastrophes are no longer ‘once in a generation’ events? Scientists are developing tools to meet this challenge—but most are linked to biotechnology that are currently in the crosshairs of activists. According to the Alliance for Science at the Broad Institute:

In order to help plants tolerate abiotic stresses, including drought, researchers identify the particular genes that are involved, and then edit these genes to facilitate plant resilience. Some plant genes enhance the deleterious effects of abiotic stresses, known as sensitivity genes….

Genome editing strategies, particularly CRISPR-Cas, have been used in several plant species, including grain, vegetable, and fruit crops, to improve abiotic stress tolerance by disrupting these genes. Research is also under way using CRISPR-based gene editing to improve drought tolerance in wheat, cassava, papaya, sugarcane and cotton.

If the opponents of agricultural genetic engineering succeed in blocking the cultivation of crops altered by new breeding technologies, they will not only harm farmers, they will accelerate the growing mistrust of science. Anti-GE opponents encourage the delusion that we can pick-and-choose the science we want to believe. But science is not an a la carte menu nor a popularity contest; it’s a fact-based process, a method of inquiry based on observation and experimentation that eventually yields consensus (but is always open to revision if new evidence should emerge). Whether one “believes “in the human contribution to climate change or not, the science evidence is incontestable; the same goes for the genetic engineering of crops.

“We simply cannot do without genetic modifications,” says Czech plant geneticist Jaroslav Doležel. “Cultivation of crops with a modified genome and resistant to diseases and pests will make it possible to dramatically reduce burden of pesticides on the environment and will be one of the key measures leading to sustainable agriculture.”

Farming should not be idolized. To cultivate crops, farmers need to overcome the hazards that Mother Nature throws at them—pest infestations, crop diseases that decimate yields, droughts, heat waves, cold spells and floods. Farmers go to war with nature every day. They arm themselves with necessary tools — fertilizers, insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, biotechnology, artificial intelligence and robots—to win the never-ending battle to grow bountiful crops (and hopefully earn a profit while doing so).

“The European Commission has finally realized the unsustainability of the situation if Europe does not adopt gene editing,” Doležel says. “There is no other way. Otherwise Europe will become a museum of agriculture.”

Steven E. Cerier is a retired international economist and a frequent contributor to the Genetic Literacy Project