However, neonics have become embroiled in a multi-year controversy in Europe and North America over whether they hurt beneficial species, specifically honeybees and wild bees. For years, advocacy groups critical of conventional agriculture, relying almost entirely on laboratory studies, have argued that the pesticide weakens or kills honeybees. Field studies contradict the lab reports, and now even the most ferocious anti-neonic advocacy groups, such as the Sierra Club, have recently reversed course, saying the latest evidence does not support an impending ‘bee apocalypse’.

Some of these groups have raised questions about the health of wild bees, which are more difficult to monitor and for which very little data exist. There are genuine concerns about how healthy bees, which face a range of challenges, from deadly mites and the chemicals used to control them to climate change to urbanization. But no clear link has been made to neonicotinoids.

EU bans neonics

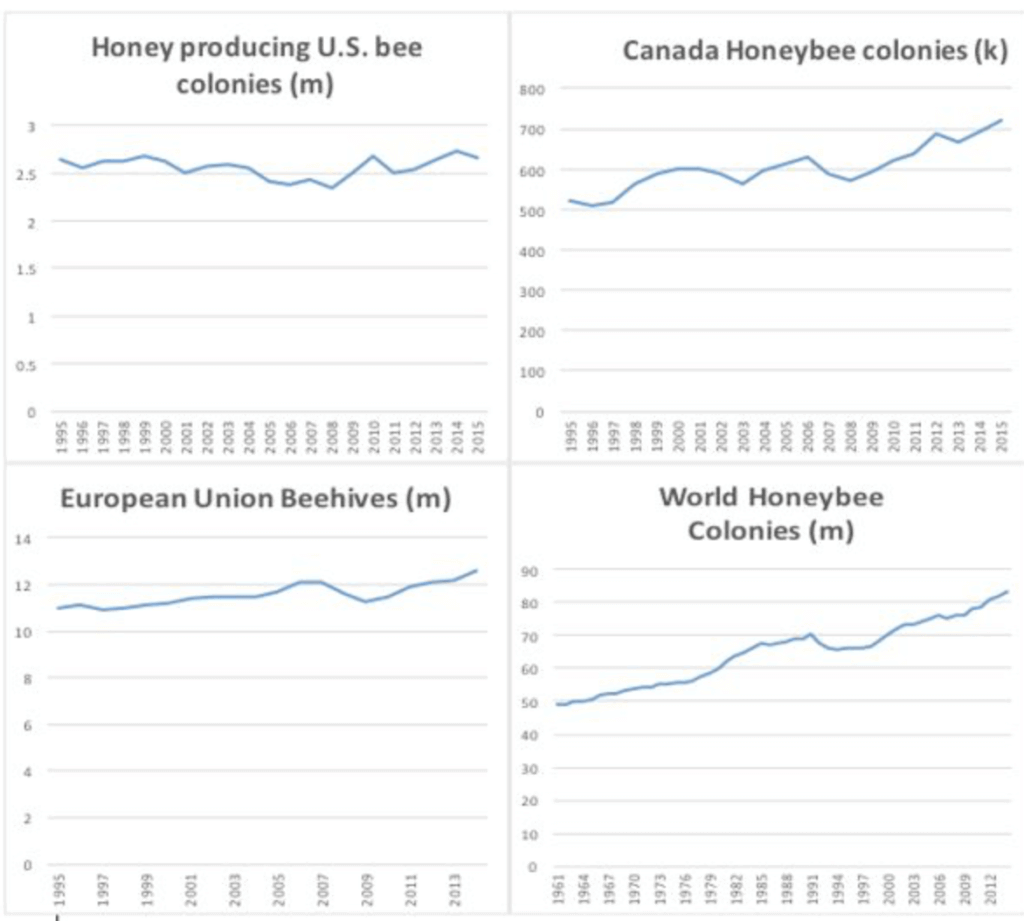

Canada’s move comes about five months after the European Union announced its decision to ban all outdoor uses of neonic pesticides after December, 2018—making permanent and expanding what was originally a two-year moratorium (imposed five years ago) on the use of these pesticides on flowering crops. The EU ban—a years-long objective of anti-pesticide campaigners—was based on claims that neonics pose a threat to honeybees, wild bees and other pollinators. This despite the fact that honey bee populations have been steady or rising in Europe and North America during the entirety of the two decades since neonics were introduced

and have been rising worldwide for over a half-century. The position also ignores the fact that the 2 percent of wild bee species responsible for 80 percent of crop pollination—putting them into greatest contact with neonics—appear to be under no threat of population decline.

The EU reached its decision after years of prodding by activist beekeepers—mostly small hobby owners—and pesticide opponents. There have been dozens of mostly laboratory studies and reports exploring every conceivable mechanism through which neonics could harm bees. But full-scale field studies—the most realistic metrics—have consistently contradicted the lab research.

Inexplicably, the EU ‘Bee Guidance Document’ (BGD)—used as the basis by which politicians made the decision to extend the moratorium—excluded most field studies, raising accusations that the process was rigged. For instance, it specified that bees used in the field tests could not show a mortality rate greater than seven percent when the natural fluctuation of honey bee colony populations is three times higher—up to 21 percent—making it impossible to demonstrate that pesticide-related mortality did not exceed the determined threshold.

Just as impossible was the BGD’s spatial separation requirements for field test fields, which required an area of 173 square miles—seven times the size of Manhattan or four times the size of Paris—for a single full-scale test. It was generally agreed that such a requirement simply couldn’t be met in the European landscape.

The result was that the EU did not evaluate the most powerful evidence, which made a persuasive case that real-world hive activity appears to neutralize the impact of the tiny amount of neonics bees were exposed to. They instead based their evaluation almost exclusively on laboratory studies that consistently overdosed honeybees while ignoring real world circumstances.

Canadian switch

In aligning Canada with the EU’s neonic ban decision, PMRA took a stunningly different tack as it was well aware that the field data on honeybees and wild bees did not support a ban. The agency turned to a ‘special review’ of the neonicotinoid pesticides Thiamethoxam and Clothianidin begun in November, 2016 (coinciding with PMRA’s decision to phase out the oldest, and arguably most redundant neonic compound, Imidacloprid). It concluded that these two neonics did pose a threat—but not to bees and pollinators! Rather to aquatic invertebrates, specifically midges and mayflies.

What? It’s fair to say this curve ball took almost all observers by surprise. After all the arguments—based on roughly a decade of studies, claims and counter-claims—about the supposed neonic threat to honeybees and other pollinators, PMRA took 18 months to pull a completely new rabbit out of the regulatory hat.

PMRA’s analysis and conclusions were considered odd by expert scientists in the field. The document alleged potential harm to midges and mayflies across Canada’s 4 million square miles. But the data was scant

to say the least. Beyond a couple of ‘mesocosm’ experiments (in artificially constructed aquatic micro-environments testing effects on the species placed in them), no one has direct evidence of diminished midge and mayfly populations. PMRA admitted this in an early September webinar explaining its proposal. That’s because no one knows for sure what these populations are, or how they fluctuate, in the first place.

In the absence of evidence of direct harm to midges and mayflies (or other aquatic invertebrates), PMRA fell back on judging whether measured concentrations of these neonics in water monitoring data exceeded their ‘thresholds of concern’ for aquatic invertebrate safety, as PMRA explained in its initial August technical briefing on its assessment and its September webinar. But PMRA concedes that its data on detected concentrations of neonics in freshwater samples is incomplete and inconsistent: robust, they claim, for Ontario and Quebec; limited and partial for the western provinces.

The west, however, comprises the bulk of Canada’s land area producing as much as 63 million acres of row crops, and using more neonic pesticides by volume than elsewhere in Canada. Despite information collection limitations, PMRA says that what water data it has from ‘out west’ reveals neonic concentrations that regularly exceed their ‘thresholds of concern’ for adverse effects on aquatic invertebrates.

Which brings us to those thresholds of concern—or of ‘acceptable risk’—and how they are established. It turns out that the key to PMRA’s regulatory conclusion is the radically conservative threshold it chose to set for ‘acceptable risk’—PMRA’s statutory criterion—to aquatic invertebrates. PMRA chose 1.5 parts per billion (ppb) for acute exposure of aquatic invertebrates to the Bayer Corporation’s neonic Clothianidin—and 1.5 parts per trillion(ppt) for chronic (long-term) exposure of aquatic invertebrates. At these concentrations, PMRA judges that 95 percent of aquatic invertebrates would be safe from any harmful effects.

But the US EPA’s preliminary aquatic invertebrate assessment for Clothianidin adopted an acceptable risk threshold (that it considered reasonable and conservative) of 50 ppt for chronic exposure—more than an order of magnitude higher than PMRA’s number! To put that in context, Christy Morrissey, the neonic critic at the University of Saskatchewan, adopts an acceptable chronic exposure threshold to Clothianidin of 35 ppt for aquatic invertebrates. (Bayer says its research shows that Clothianidin concentrations of 100–200 ppt are safe when aquatic invertebrates are exposed to them long-term.) The PMRA figure appears specifically designed to ensure that neonics would be found at ‘dangerous levels’.

Curiously, according to PMRA’s toxicity data, as presented in its September webinar, Syngenta’s Thiametoxam was shown to be significantly less toxic to aquatic invertebrates. Yet PMRA judges that it nevertheless merits precisely the same 3-5 year phase out as Clothianidin.

Here are the suspicious decisions PMRA made as it evaluated these pesticides: Its seeming ‘rush to judgement’ on the basis of aquatic effects, only recently and briefly examined; the ultra-conservative ‘acceptable risk’ threshold that is exclusively PMRA’s prerogative to establish; prescribing precisely the same phase-out for two pesticide products with strikingly differential environmental toxicities.

Just last week, Canada’s Canola Council urged for a slow down in the decision process, arguing that most of the data was based on fragmentary modeling and not on hard evidence.

All this looks even more inexplicable based on PMRA’s 2017 review of these two neonics’ effects on pollinators. Those green-light reviews led to the re-registering of these products with relatively minor adjustments in their permitted uses and required mitigation measures.

Canada’s western farmers, who have seen no signs of the issues PMRA is basing its decision on, are baffled and angered. To them, PMRA seems to be imposing a drastic step on the strength of an 18-month review of incomplete and inconsistent water sampling data, applying an unrealistically conservative standard of ‘acceptable risk’ in the absence of any actually demonstrated ecological harm. Faulty and biased as it is on the science, even the EU’s neonic ban, justified by supposed harm to bees, at least had the appearance of greater robustness since for years it has been in vogue in the scientific community to study every conceivable effect of neonics on bees.

Aquatic invertebrates? Barely.

Farmers’ dilemmas

Farmers risk losing an essential tool—neonic seed treatments—for protecting their crops, notably, Canada’s lucrative 23-million-acre canola harvest. For instance, flea beetles can completely destroy a newly planted, untreated canola field in a matter of days. That’s faster than a Canadian farmer can scout the damage and organize a spraying operation with remaining available pesticides., Substitutes are less effective, more toxic to the environment and more costly. PMRA acknowledges that they do not compare the environmental toxicity of the replacement spraying to the neonic seed treatments they propose to phase out. All of this is a ‘big hit’ for Canada’s farmers to absorb on the strength of PMRA’s evidence so far.

What’s more, since it typically takes 11 years and an investment of $286 million to register a new pesticide for the marketplace, PMRA’s extra two-year grace period for phasing out neonics in applications for which there is no currently available alternative is wishful thinking. If the new alternative doesn’t exist now or isn’t in the final stages of regulatory approval, it will never be ready in time.

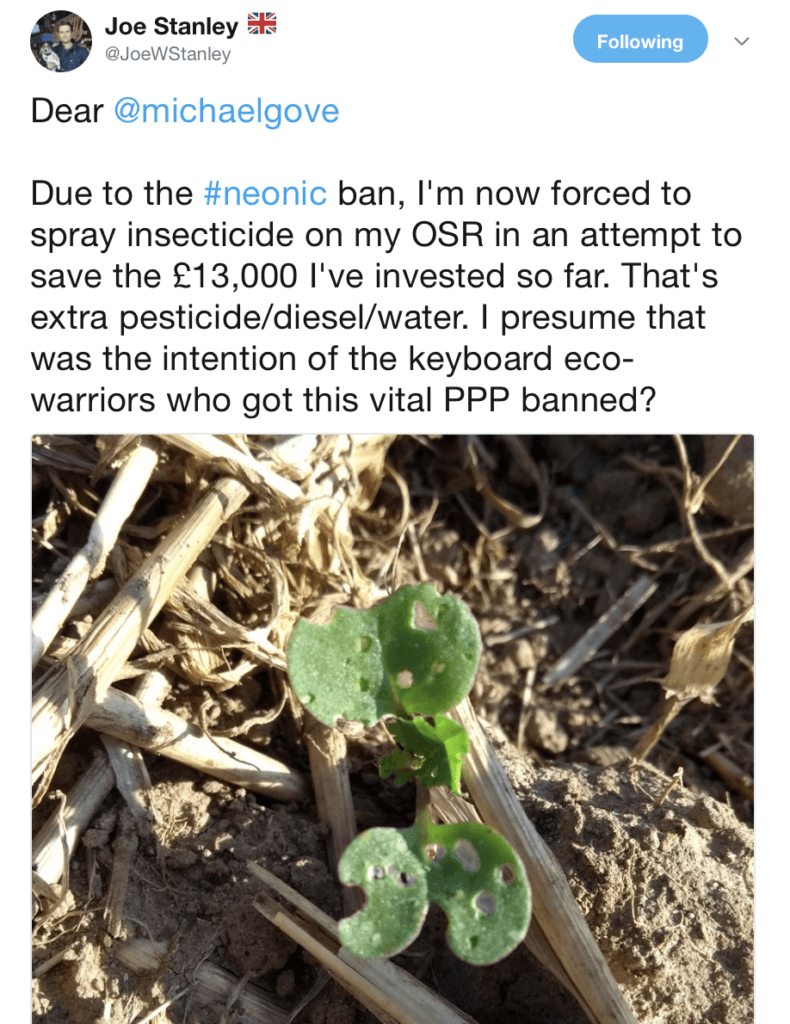

A recently released study by scientists at the UK’s University of Newcastle on the effects of the EU’s neonic ban on oil seed rape (a relative of Canada’s canola) production may offer a foreshadowing of what PMRA’s phase-out recommendation portends for Canadian agriculture. The survey of more than 200 UK farms documents a roughly 24 percent reduction in the area of growth in the UK from its pre-ban peak in 2012. Crop losses to the cabbage stem flea beetle, owing to the loss of neonic seed-treatment, were shown to exacerbate economic and agronomic factors.

As one UK farmer tweeted, ‘Due to the #neonic ban, I’m now forced to spray insecticide on my OSR in an attempt to save the £13,000 I’ve invested so far. That’s extra pesticide/diesel/water. I presume that was the intention of the keyboard eco- warriors who got this vital PPP banned?’

warriors who got this vital PPP banned?’

Just last month, UK officials reported that “swarms” of the cabbage stem flea beetles devastated oil rapeseed crops across the country, sometimes consuming entire fields within 48 hours. To make matters worse, experts in Britain are warning that pests that target other crops have developed resistance to the key alternative pesticide to neonicotinoids. The National Farmers’ Union says that about 60 percent of flea beetles are resistant to pyrethroids, the highly toxic and environmentally unfriendly alternative to neonics.

With Canada’s canola production area roughly 20 times larger than the UK’s OSR cultivation, losses on a UK scale for Canada’s farmers would be a major blow.

Obviously, banning anything can be rationalized if you set the standard of safety too low — in this case, unreasonably low. To all appearances, it would seem that Canada’s PMRA, under pressure from the Trudeau government and its environmentalist supporters in Ontario and Quebec, has grasped for an excuse to ban neonics. PMRA’s three- to five-year phase out plan may be a ‘split the baby’ compromise to soften the blow for Canada’s western farmers, whose economic interests are being, typically, sold out to satisfy Canada’s urban centers ‘out east.’

What’s going to happen next in the US is clear: Based on these recent announced bans, the EPA is about to come under tremendous pressure from advocacy groups to copy-cat the neonicotinoid restrictions in Canada.

Jon Entine, executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project, has been a journalist for more than 40 years, as a writer, network television news producer and author of seven books, four on genetics and risk. BIO. Follow him on Twitter @JonEntine