And that explains why I so desperately despise these evil corporate bastards and will do anything I can to shut them down.

After 25 years of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) investments; after meeting their millennial sustainable development commitments; after years of companies playing the role of good corporate citizen, public benefactor and agents of societal change and social justice; after establishing and enforcing ethical codes of conduct (which governments and NGOs don’t have); after meeting all Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) targets, why is it that the only constant for most industries today is the growing public revilement of them?

I recently gave a speech at an industry trade association event and a questioner started his intervention apologetically with: “OK, we’re industry, but…”. The last two decades of relentless anti-industry attacks in the media, cinema and policy arenas have taught industry actors to be quiet in public, but they should not be ashamed of what their innovations and technologies have brought to humanity. We are living longer with a better quality of life, direct access to better food while feeding a growing global population, enjoying amazing personal communications devices, travelling faster and safer and accessing information in seconds. But all we hear about industry in the public sphere is resentment and animosity. This is the “Industry Complex”.

The forces of hate

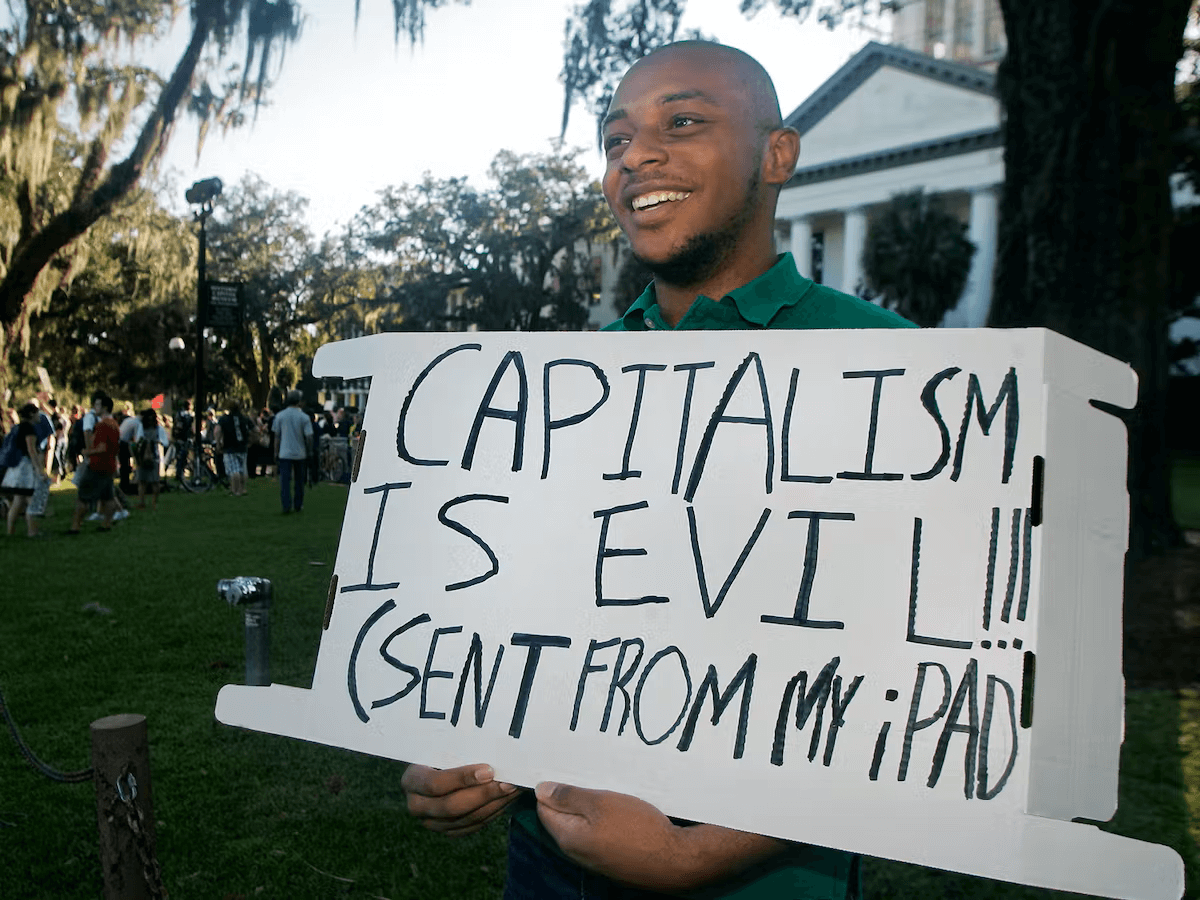

Young people march on the streets with signs condemning corporations and capitalism rather than looking to corporations for innovative, low-carbon solutions. Aid programmes that promise technologies to developing countries get side-lined because activists identified corporate partnerships. Policymakers in Brussels are no longer allowed to speak to corporate officials (for fear that they would attract condemnation by civil society activists). Any scientist or academic who does research with industry or takes their funding is forced to accept a life on the fringes of his or her field, forever labelled as an “industry-funded scientist”. As the first article in this series argued, all industries (except those sanctioned by the green lobby) have been tobacconised – at best tolerated but never welcome in society.

But who decides which industry sector to condemn? How has a major societal actor, employer and solution provider become so vehemently vilified by other stakeholders, the media and policymakers? What did industry leaders (fail to) say or do to create such a dismal narrative? Are these companies victims of their own success (the prosperity brought about by decades of impressive technological innovations being now taken for granted)? As mentioned in Part 1 of this series (on the tobacconisation of industry), all industries are being portrayed as evil along the same strategies as the campaign against the tobacco industry.

Four years ago I wrote a three-part analysis based on my 20 years of experience trying to develop stakeholder dialogue in the Brussels policy arena. My conclusion was that this dream of dialogue was long-gone dead. At the time I had postulated several causes: from the rise of social media populists, the decline of corporate advertising in traditional media, the creation of silos promoting confirmation bias and tribal groupthink or the need for Hollywood to find a new source of evil after the end of the Cold War. I had labelled this “The Age of Stupid”.

But since that trilogy, the narrative has worsened. The echo chambers became hermetically sealed – people rarely have occasion to come in contact with those with other ideas. The rise of hashtag social justice campaigns from #metoo to #BLM hardened and crystallised the left. Add the growth of climate death cults like Extinction Rebellion identifying capitalism as the source of all of the world’s problems and the conclusion was simple: the despicable corporate world, led by racist white, middle-aged males, needed to be stopped. (As a white, middle-aged male who supports the benefits of capitalism and risk-taking, I took this personally.)

Trust in industry, its technologies, its innovations, its leaders… became non-existent. The corporation was denormalised, tobacconised and excluded from public discourse – thus an easy target for opportunists spreading fear and outrage.

Expressing hatred toward industry became the work of poets and playwrights. You could not be respected unless you sided with environmentalists, agroecologists and victim associations. Bring in the right mix of angry and cleverly organised teenagers and a new generation of anti-industry militants is born. Most of the people throwing brown beans at artwork or spray painting corporate offices are from a privileged class that have never experienced want. The tragic consequence of such “altruistic” zealot demonstrations is that the victims from the policy decisions they are forcing through are the most vulnerable in society, and will never be heard.

What is unique in this most recent wave of radicalisation is that anti-capitalist idealism usually peaks at times of prolonged economic hardship and not during two decades of fiscal expansion. As we are entering into what looks like a prolonged period of economic decline, with a widening gap between haves and have nots, we can only expect this hatred to increase as more of the sacrifices are burdened on the have nots (who now have social media accounts and large followings). The other twist is that the green, privileged class may become the target of popular outrage against greenflation (but I expect their communications geniuses are far ahead of the curve on that one).

What is “industry”?

This may seem like a strange question, but industry is no longer merely represented by those grey factory smokestacks dumping suffocating smoke into the air and toxic sludge into the rivers. Most of those 1880 Industrial Revolution images, we’re told, have been offshored to emerging markets (perhaps another reason it is so easy to attack industry – very few people in the West still work in factories). “Industry” is now an umbrella term referring to any capitalist venture that may involve risk, inequity and unequal access to markets. In a zero-risk world, risk-takers are easily condemnified on the altar of shared social justice.

When society is facing impending doom (eg, climate change, biodiversity losses, endocrine disruption…), industry in one form or another is quickly blamed. The financial, tourism or fashion industries have been criticised for the environmental consequences of their developments. We are made fat by the food industry, poisoned by plastics producers and deceived by Big Pharma. Industry and globalisation were even seen as the cause of the COVID-19 pandemic. The simple solution to any problem today is to get rid of industry involvement and, after which, nature will heal itself (and us).

The narrative is not only about rejecting industry’s money and influence – it is about how industry has destroyed our freedom to choose. I couldn’t say “I got fat from my bad choices“, but rather it was the food industry, packaging their sugars, fats and chemical additives, that made me fat. I’m once again a victim of evil industry! But the most unique extension of industry is the recent angry assault on farmers … yes, the people who grow our food are now part of industry (and perhaps the most evil at that).

Last weekend, the absurdity of the hateful attacks on farmers reached their zenith with the brutal battles in the fields outside of Sainte-Soline in France (see cover image). Facing years of droughts, French farmers have been building irrigation ponds to lower the exposures to crop losses, collecting water during the wetter winter months (most often from rivers) to use in the dry summer months. Militants led by a backward-looking peasant farming federation (and joined in by far-left political actors) have identified this as risk-taking, attempting to own a public resource, creating advantages over other (organic) farmers and encouraging more intensive farming (not to mention using plastic to line the ponds). These ponds were identified then as part of an industry and needed to be stopped by any means. During the weekend of October 29-30, over 3000 militants descended on this French village to stop the construction of a pond that was intended to be shared by the local farming community. On October 29, in military-style battles, 61 police officers were injured, 22 seriously. On the third day, the anti-industry Luddite Revolution was finally put down … for now.

At first sight, denying farmers the means to protect their harvest, has to be seen as pure stupidity, but it signifies the evolution of the activist movement’s zero-risk narrative. Soon they will attack farmers for seeking advantage by planting carrots in straight rows and using tractors (intensive farming must be stopped to fit in with their cult ideal of food production as an expression of religious faith). We have to live within nature, suffer the consequences and not battle against it. Anyone who invests in a risk-based venture that hopes to gain an advantage (ie, capitalism) is despised and must be stopped.

This shared groupthink took what was a common-sense attempt to preserve a social good, food production, and converted it into symbols of hate (agro-industry, public resource abuse, inequality, chemicals and over-production). This is a battle against industry and capitalism and the rage of these activists overshadowed their emotional need to virtue signal their dreams for a world of rainbows and butterflies.

We can’t simply brush these people off as confused and frightened Luddites. Opportunistic activists have twisted reality, converting fear and uncertainty into a dangerously powerful political force. As one commentator on BFM decried: “This is the collapse of rationality“. Not only do they believe their hateful bullshit, they are relentlessly spreading it with a missionary zeal via an unaccountable social media propaganda tool (while the rest of us remain tolerant or uninformed).

How to regulate hate

Opportunistic policymakers and elected officials are not blind to the mob populism that wants to eliminate capitalism. The problem is that the public, at the same time, are not willing to give up the comforts fifty years of technological innovations have bestowed upon them. There is a twisted logic where people can, for example, condemn Big Pharma and then condemn the anti-vaxxers who refuse the COVID-19 vaccines. Illogic melts away under the heat of self-interest.

So this winter, governments might be able to get away with taxing energy company profits to subsidise home heating bills, but that money will only go so far. Climate taxes are at their zenith and the more industry is pummelled and punished as the root of all evil, the reality of fewer jobs and innovations will further exacerbate tensions. Food inflation should wipe out the organic food sector unless governments dig deep adding further subsidies. That the radical left grew so dramatically in a time of prolonged prosperity does not bode well for industry, corporations and capitalism in the West in the coming years as we head into recession.

Green political parties are now realigning the political spectrum, replacing the moderate left and pulling more levers of power across Europe. So we find ideologues with a naïve understanding of business and finance and who have long campaigned from the isolated fringes now making policy decisions (at a time of an energy crisis and food shortages where their solutions won’t make the situation better for a declining middle class). How long will they be able to continue to blame capitalism for their failed programmes? How much damage will they do, how many nuclear reactors will they shutter, how much land taken out of agricultural production, how much unemployment will we have from an industrial exodus – how much will we suffer before people wake up?

In times of prosperity, decision-makers can sheepishly claim they are merely doing what they perceive the public wants (and then pay the difference). The precautionary principle fit this political reality nicely as it justified inaction while delivering critical blows to industrial innovations and technologies.

- Activists claiming to represent the public say they don’t want nuclear or fossil fuel-based energy – fine, we’ll shut down the power stations and import energy from our neighbours.

- The public, we are told, don’t want chemical pesticides – fine, we’ll just put conditions on farmers that will make our agriculture unsustainable and then import from African smallholders.

- Anti-globalisation activists tell us the public doesn’t want big companies to export and import competitively on a global scale – fine, we’ll just support less efficient cottage industries.

But are we prosperous enough to continue to let the sheep lead us?

Does the public know what they want or is most of this coming from a loud minority of activist ideologues? And will the majority be heard when they lose their jobs while their energy and food costs go through the roof?

Policy by anti-industry ideology

Many of these irrational policy decisions are justified by activist anti-industry objectives.

- In the face of an energy crisis, ecologists are holding firm in Germany and Belgium against keeping some nuclear reactors from being decommissioned arguing that such a move would be supporting big business. Greenpeace claimed shutting down these reactors would give energy production back to the people. Renewables like wind and solar have the image of small, locally produced energy (from nature), enjoying a virtuous halo that belies the big companies making these technologies or managing the big wind parks and solar farms.

- Agroecologists oppose new plant breeding techniques and block African smallholders from using GMOs in their fields because it will make them dependent on big corporations like Monsanto (a company that no longer exists but still evokes passionate outrage). It doesn’t matter that technologies like Golden Rice have health benefits, use fewer pesticides (like the modified Brinjal eggplant) or are resistant to fungal outbreaks in maize, cassava and banana crops. It doesn’t matter that most of the new seed breeding innovations in developing countries take place in local, public research labs. These technologies are brandished as corporate (see the recent Corporate Europe Observatory tirade) and thus excluded from the decision process with not even a mention of their benefits.

- Arguments against the use of chemical technologies now have two new prefixes: “toxic, synthetic” chemicals. Big companies make synthetic chemicals (thus they are bad) but natural chemicals used in naturopathic remedies, homeopathy or organic farming are “non-toxic” (thus they are good), although from a scientific perspective, this arbitrary distinction is as ridiculous as the European Commission’s Green Deal aspiration for a “toxic-free environment” (I wish I were making that up).

These decisions are not based on issues of cost, efficiency and benefits, but only on an ideology built on the hatred of industry. Thus the pro-renewables and pro-organic policies dominating the European Commission Green Deal strategy are not based on facts or research but ideology. They are, in a word, irrational.

Hucksters and hypocrites

Is it any surprise that those who demand tolerance are the most intolerant towards anyone who may not agree with them. Those who demand transparency from others are the least transparent – the least willing to share information on their own funding and special interest details. Those who feel they stand up for civil liberties are the first to silence others from speaking. Their ideas are cult dogma that are not open to discussion or compromise. These are zealots who will stop at nothing to impose their views and practices on others, happily lying if it will help their cause. Very few NGOs have ethical codes of conduct that they demand their lobbyists to follow. There is no need for something so cumbersome if they enjoy the public trust.

In debates in Brussels on issues like the use of chemicals, plastics, pesticides, minerals, fossil fuels, food additives, alcohol, vaping and snacks, the European Commission has tried to create a stakeholder process of consultation and compromise. Industry will look for common ground and hope there is still room for innovative products and markets. NGOs will look at any compromise as a temporary step back in achieving their goals, demanding thus a change of strategy.

Industry looks at short-term objectives in policy debates while activists take a generational horizon. Often thee activists move into government positions and continue their campaigns internally. Many of the activists who don’t follow this path into power would take media positions or remain career lobbyists – lifers – who are not just fighting on policy issues but trying to change the policy process to their favour. And they have.

Snakeholder dialogue

NGOs have introduced deceptive policy tools like the hazard-based approach, the precautionary principle and the transparency initiative in order to make it impossible for industry to achieve any positive results in the policy process. Policymakers have allowed this as it simplifies their roles (precaution is an easy route out of complex policy issues) and industry actors in Brussels, for some reason, think these tools are codified and there is nothing they can do about them. I rarely meet an industry official entering a policy process thinking they have a chance of winning. It is often seen as a victory to limit their losses, keep their product on the market for a few more years and not let the legislation bankrupt their business. The second slowest zebra.

Industry leaders must be very frustrated with Brussels – they have come to expect regulatory losses, have learnt they are not welcome in European Commission offices, their science and data are ignored, and they have to politely listen to disgraceful, hateful slurs from these so-called preachers of equity and tolerance. I know cases of Commission officials who are very frustrated with the loud, relentless activist zealots who refuse to compromise and do anything to win. But annoyance does not translate into corrective actions – these officials have been bullied and intimidated into submission. And surely the NGOs must be very frustrated that they cannot just get everything that they are demanding.

I don’t think this is what was meant when the European Commission started on the process of stakeholder dialogue some two decades ago with the White Paper on Governance. Perhaps going back to a technocratic approach to most EU policies might not be a bad idea? This is the topic for the next analysis.

Activists have been successful in destroying public trust in industry. Corporations have been excluded from EU policy processes, their research data discredited. Ideologues build their organisations around fear and loathing of industry and for a large part, industry has remained silent and polite. The Industry Complex is that this concerted attack on corporations has gone unanswered for far too long, that industry is content to be the second slowest zebra in the herd while continuing to play a losing policy game with tools like the precautionary principle ensuring no chance of success at all. Capitalism is being written out of EU policy.

My apologies for being dark (but I’ve learnt recently I am not alone here) but if industry does not change its strategy, at least in Europe, it will disappear. Part 3 of this series will look at one positive element that industry will need to capitalise on if it is to survive.

David Zaruk has been an EU risk and science communications specialist since 2000, active in EU policy events from REACH and SCALE to the Pesticides Directive, from Science in Society questions to the use of the Precautionary Principle. Follow him on Twitter @zaruk

A version of this article was originally posted at Risk Monger’s website and has been reposted here with permission.