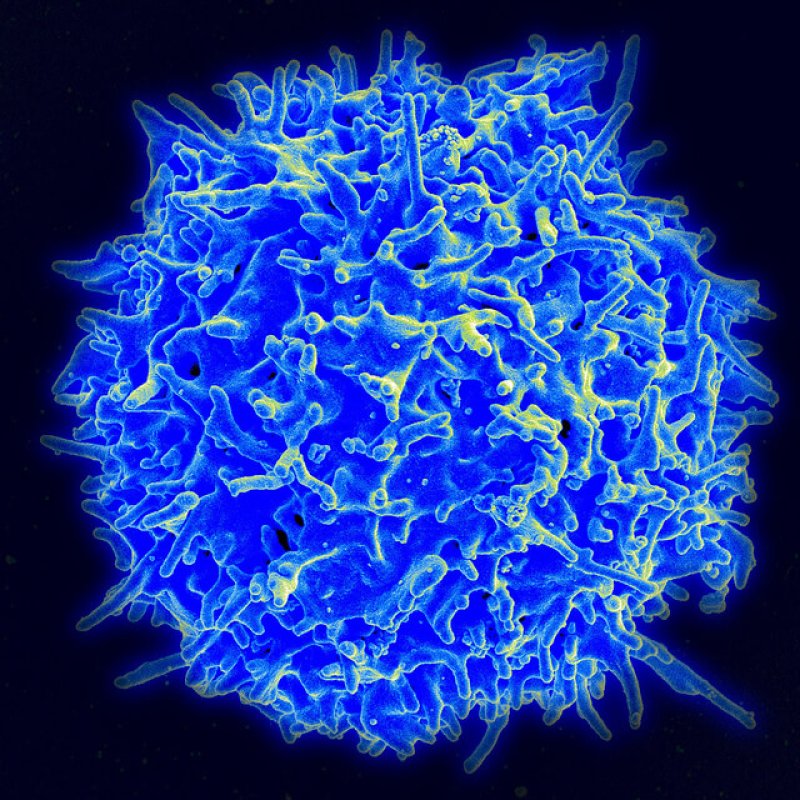

The idea of training the body’s immune system to fight cancer has been around for decades. Immunotherapy was first approved in the early 1990s. Doctors used a hormone called interleukin-2 (IL-2) alongside chemotherapy. The IL-2 protein are like steroids for the immune systems killer T-cells. It sends them into overdrive. Consequently, they kill some cancer cells.

What happened to immunotherapy after that was lackluster at best, Heidi Ledford writes at Nature:

After that 1992 approval, researchers and pharmaceutical companies spent years trying to develop new immunotherapies that could produce success stories like Gorman’s. But those attempts failed to live up to their promise in the clinic, leading to decades of frustration.

But now, 20 years after the first, limited success, immunotherapy is hitting it big. And the business and biotech communities are interested, so much so a particular immunotherapy treatment and the CEO of Novartis, the company developing it, are on the cover of the May 26 issue of Forbes.

The headline asks the question, “Will this man cure cancer?” But, like so much hype around new therapies, the medical evidence answer is a very, very qualified yes. The treatment will probably cure many cases of a few cancers. But in the field of oncology, that’s enough to make a lot of money. “According to data provider IMS Health, spending on oncology drugs was $91 billion last year, triple what it was in 2003,” Matthew Herper at Forbes wrote in the story.

The treatment uses chimeric antigen receptor T-cells or CART. Doctors take immune T-cells from a patient’s blood, add genes that stick a receptor for cancer cells on the T-cells surfaces, grow a lot of them and put them back in the patient. These bad boys then go to town on cancer cells. CART works really well for a rare types of leukemias– its nearly 90% effective– and half as well for the more common type. But so far, there is little to no data it could work on solid tumors, which often build protective layers of tissue separating themselves from the body’s immune system. From Forbes:

Downsides: “So far, it’s only blood cancer, it’s high technology, it’s customized therapy, it’s going to require major investment,” warns Clifford Hudis, president of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, who is nonetheless excited about the cells… Though the cells are “amazing,” says Charles Sawyers, the past president of the American Association for Cancer Research and a Novartis board member, “what we don’t know is how broadly does this scale?” Penn and Novartis will soon begin studies in mesothelioma, a lung cancer, to start answering that question.

In fact, four patients died during a CART trial aimed at a protein called MAGE-A3 that appears in adult cancers. A very similar protein is expressed in brain and heart tissue. The failed trial underscores the need for very specific targets, and one protein might not be enough. Nature reports:

In response to the deaths, ImmunoCore, an immunotherapy company based in Abingdon, UK, developed new bioinformatic methods to search for signs that any possible T-cell target could be expressed in normal tissue.Michel Sadelain, a cancer geneticist at Memorial Sloan Kettering, hopes to engineer T cells that target two proteins, both of which would have to be expressed on a cell for the T cells to destroy it. The idea, he says, is that the chance that a healthy cell will have both targets on its surface will be slim.

Novartis CEO Joseph Jimenez is refreshingly honest about the cost of the treatments, still to early to put a price tag on, and the oncology drug market in general:

“What you know is not going to happen is the ability to stack therapies on top of each other at the current price and expect people to pay,” he says. “ The whole oncology pricing structure needs to be rethought because it’s reached the level that is not going to be sustainable for the long term… ”This is actually what’s driving his strategy of bulking up his cancer division–so it can compete–and at the same time betting on the wildest technology. He expects “a new brutal world” for health care companies as countries around the world are forced to double health care spending because of age and illness over the next ten years.

What is definitely clear from these stories is that the business of immunotherapy is ramping up quickly. The science, however, as befits the history of immunotherapy in general, will likely continue in fits and starts.

Sources

Is This How We’ll Cure Cancer?, Matthew Herper, Forbes

Cancer treatment: The killer within, Heidi Ledford, Nature

Additional Resources:

- DNA “cloaking devices” sneak past the immune system, could deliver medicine and identify disease, Kenrick Vezina, Genetic Literacy Project

- Patient’s Immune System Harnessed to Attack Cancer, Ron Winslow, Wall Street Journal