Many countries in the developing world are likely to bear the ecological brunt of climate change and population increase. Meanwhile, the controversy over biotechnology rages in India, Costa Rica, the Philippines and Uganda, among many countries.

Many organizations in the developing world point to biotechnology as the answer to feeding the nine billion people that the UN expects will fill the planet by 2050; others cite low-input small farms as the solution. In the latest issue of National Geographic, writers Craig Cutler and Tim Folger address these challenges in “The Next Great Green Revolution.”

The United Nations forecasts that by 2050 the world’s population will grow by more than two billion people. Half will be born in sub-Saharan Africa, and another 30 percent in South and Southeast Asia. Those regions are also where the effects of climate change—drought, heat waves, extreme weather generally—are expected to hit hardest. Last March the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that the world’s food supply is already jeopardized.

This isn’t the first time that scary predictions of a hungry future have loomed over the global South. In the 1960s, Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich (now president of the Center for Conservation Biology) predicted that famines would kill hundreds of millions of people in India. Nobel laureate Norman Borlaug, who died September 12, 2009, was a major player in defusing this so-called “population bomb”, by increasing wheat yields.

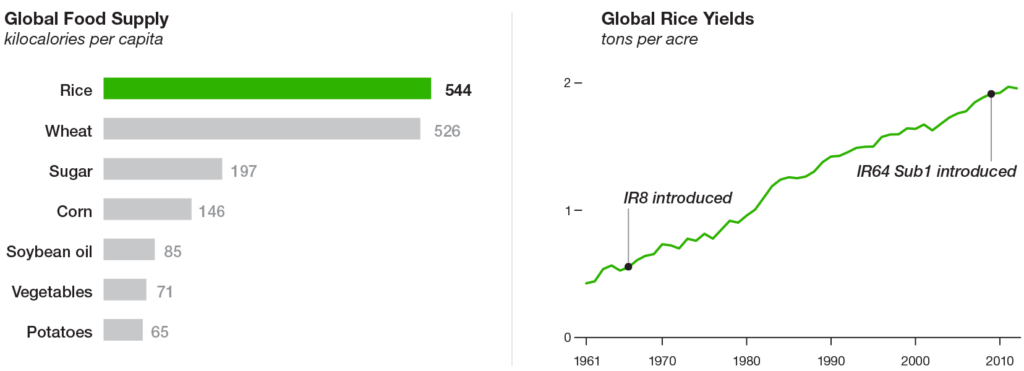

Through selective breeding, Norman Borlaug, an American biologist, created a dwarf variety of wheat that put most of its energy into edible kernels rather than long, inedible stems. The result: more grain per acre. Similar work at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines dramatically improved the productivity of the grain that feeds nearly half the world. From the 1960s through the 1990s, yields of rice and wheat in Asia doubled. Even as the continent’s population increased by 60 percent, grain prices fell, the average Asian consumed nearly a third more calories, and the poverty rate was cut in half.

To keep doing that between now and 2050, we’ll need another green revolution. There are two competing visions of how it will happen.

Groups such as the Consortium of Indian Farmers Association (CIFA), the Biotechnology Society of Nigeria and AfricaBio believe that biotechnology solutions can help with poverty and hunger in the global South. Nompumelelo H Obokoh, CEO of AfricaBio, maintains that “[b]iotechnology, while not the complete answer to food insecurity at the household level in South Africa, can help to ensure that nobody goes to bed on an empty stomach,” and interviews small farmers in South Africa about their experiences with GM crops.

The Philippine Rice Research Institute works on developing transgenic Golden Rice to help fight nutrient deficiency, especially in children.

South African scientists led by Dionne Shepherd are working on a marketable strain of transgenic maize resistant to maize streak virus. This is especially notable because maize streak virus is endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. It could be the first African-produced GMO, created with African problems in mind. Meanwhile, scientists in Uganda are testing GM cassava resistant to brown streak virus.

Groups like the African Centre for Biosafety have another vision, one that focuses on reducing the input of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. “We are outraged that South Africa – the only country in the world to permit the cultivation of genetically modified staple – continues to do so despite a large and growing body of scientific evidence pointing towards severe potential health risks of consuming GM crops, including maize,” said Mariam Mayet, Director of the African Centre for Biosafety, in a recent article.

Food Sovereignty Ghana believes that problems in food security are the result of “the neo-liberal agenda of the imperialists… which have the focus on marginalising the small family farm agriculture that continues to feed over 80% of Africa and replacing them with governance structures, agreements and practices that depend on and promote unsustainable and inequitable international trade and give power to remote and unaccountable corporations.”

The GM crops that exist are safe, and provide numerous benefits to the environment. They also provide a valuable tool for innovative problem solving. It’s valuable to continue to research them, and use them. But no one is suggesting that we abandon other avenues of research. For example, traditional breeding seems to be the best solution for drought tolerance right now (though I would hasten to add that I support continued research into drought-tolerant GM crops).

Planting GM crops can also be beneficial to small farmers. But not all small farmers are the same. Some can’t afford fertilizer, much less high-end seed. And good stewardship of GM crops includes planting them correctly, which may involve information exchange and infrastructure that is not available to small farmers.

Cutler and Folger end their report with a plea for coexistence. Indeed, even biotech corporations like Monsanto stress the coexistence of GM and organic crops. So where is the controversy? Most of us already seem to be following the middle way.

It’s not choosing one type of knowledge—low-tech versus high-tech, organic versus GM—once and for all. There’s more than one way to increase yields or to stop a whitefly. “Organic farming can be the right approach in some areas,” says Monsanto executive Mark Edge. “By no means do we think that GM crops are the solution for all the problems in Africa.” Since the first green revolution, says Robert Zeigler, ecological science has advanced along with genetics. IRRI uses those advances too.

Additional resources:

- The next Green Revolution, National Geographic

- Can biotechnology rescue diseased Florida orange crop?, National Geographic

- Norman Borlaug inspires biotech-based second ‘Green Revolution’, Business Standard

- Nobel laureate in medicine: GMOs are ‘key tool’ to address global hunger, Boston Globe

- Role of biotechnology in global food security cannot be dismissed for ideological reasons, Guardian

- Can crop biotech save the cassava?, PLOS One