Any announcement of a new, more effective antibiotic could not come at a better time. The number of bacterial infections and outbreaks from contaminated food has afflicted tens of millions of Americans every year. Meanwhile, Current antibiotics have become less effective, thanks partly to overuse and partly to resistance from new, dangerous strains of bacteria. At the same time, drug companies haven’t produced many new antibiotics.

So you would think a report demonstrating that a protein produced by E. coli bacteria to destroy other, more dangerous E. coli bacteria, could be easily produced in plants to stop these food-borne outbreaks would come as welcome news.

Overall, it did–among science advocates. But progress in developing colicins from plants has run into two significant sources of opposition. Influential organic food industry linked advocacy groups have long been hostile to the concept of “biopharming”–growing plants engineered to make drugs. According to a Friends of the Earth official:

Growing medicines in plants has serious implications for both human health and the environment. We recognise the need for affordable medicines to be made available to people with life-threatening illnesses, but this research could have widespread negative impacts. Food crops in the United States have already been destroyed because of contamination by experimental `pharm’ crops.

The second challenge is a US regulatory approval structure that has been hesitant to approve such drug products. Henry Miller, who once headed the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology:

Biopharming’ — the once-promising biotechnology area that uses genetic engineering techniques to induce crops such as corn, tomatoes and tobacco to produce high concentrations of high-value pharmaceuticals (one of which is the Ebola drug, ZMapp) — is moribund because of the Agriculture Department’s extraordinary regulatory burdens. Thanks to EPA’s policies, which discriminate against organisms modified with the most precise and predictable techniques, the high hopes for genetically engineered ‘biorational’ microbial pesticides and microorganisms to clean up toxic wastes have evaporated.

E. coli is one of many bacteria associated with food-borne bacterial infections. One strain, the E. coli O157:H7, has been responsible for 75 percent of those outbreaks. According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 9.4 million illnesses arise from a known pathogen in food. In 2013, 818 outbreaks sickened 13,360 people, sending 1,062 to the hospital, and killing 16. E. coli is by no means the only pathogen associated with food-borne illnesses, but it has been responsible for a total of 100,000 illnesses and 90 deaths (from food and other entry points) every year. Also, while organic food is not the only source of these illnesses, the agricultural production method is far from an innocent bystander.

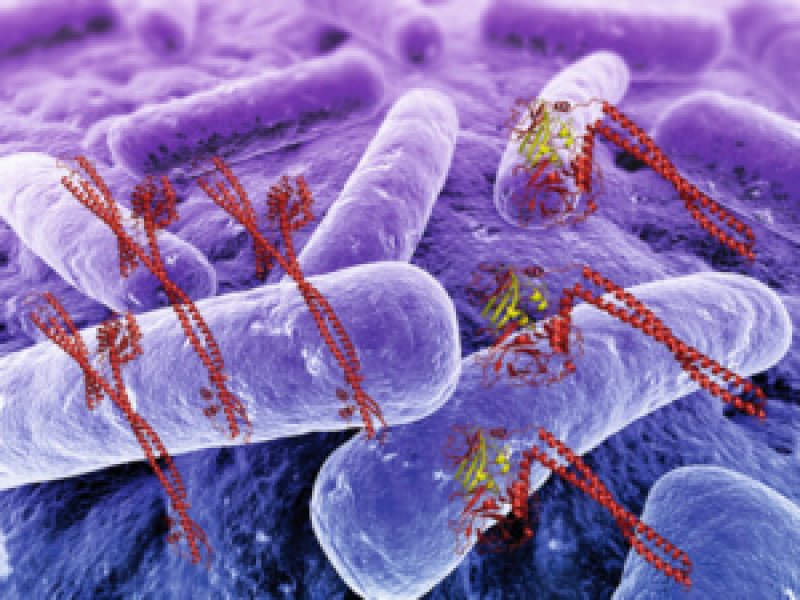

Enter E coli colicins

Colicins, the protein expressed by E. coli to destroy other E. coli, have been researched for more than 90 years, mostly for their potential as a combatant against infections from E. coli and other bacteria. They work by specifically killing other E. coli that compete with the E. coli host that made the colicin. Colicins aid their E. coli “parents” by removing other competition for food. There are several strains of colicins; some work against other bacteria like Salmonella, while others are devastatingly effective against pathogenic E. coli. They also are resident in E. coli that reside in human and other animal intestinal systems.

In the PNAS announcement, two German biotechnology companies, Nomad Bioscience and Icon Genetics, found that a number of plants, including tobacco, beets, spinach, chicory and lettuce could be engineered to express colicin proteins in high enough volumes to be commercially viable.

The plants made production more viable because previous researchers found that when engineering microbes to produce colicins, the colicins killed the hosts. The German researchers found that colicins were non-toxic to plants. The colicins were 50 times more active in their antibiotic activity against bacteria when compared to traditional antibiotics, so that very small volumes could protect beef, pork and other foods from contamination. “All of the food outbreaks that have been recorded in the last 15 years or so could have been controlled very well by a combination of just two colicins, applied at very low concentrations,” said Yuri Gleba, CEO of Nomad Bioscience. The group plans to submit its plant-expression colicin model to the US Food and Drug Administration for recognition as GRAS (generally recognized as safe).

It’s not easy, getting GRAS

And therein lays a rub. Nomad and Icon will not be the first to apply for GRAS for colicins from the FDA. In 2009, a Kansas company called Ivy Animal Health (now owned by Eli Lilly) withdrew its submission for a form of colicin to be used as an antibiotic (it’s not certain why). In 2007, scientists from North Carolina State University and the University of Iowa reported that a form of colicin could prevent E. coli infection in post-weaned piglets, which is responsible for health of diarrhea-related deaths in young pigs. This finding, too, never resulted in approval of colicins from the FDA, but showed colicin’s potential as a food additive.

The various government agencies responsible for approving antibacterials in animals have been slow in approving new treatments, except for some vaccines, a 2012 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report found. One reason for this was that few companies applied for government approval of such treatments. The GAO urged the US government to search out new ways to find treatments that could reduce E. coli and other outbreaks in cattle and other livestock.

As new products appeared on the horizon, advocacy groups skeptical of technologically based food solutions, such as the Environmental Working Group, escalated their opposition campaigns. Even though EWG urges consumers to wash organic food to rid it of bacteria and other germs, they also have opposed biopharming techniques like those proposed by the German biotech companies which could more efficiently achieve the same goals.

Compounding the challenges, the United Nations, US FDA and other agencies have long opposed (or have been very reluctant to approve) biopharming techniques, with international health consequences. And some scientific associations, like the Federation of American Scientists, have advised treading slowly until risks are worked out. Colicins don’t face an easy path.

Andrew Porterfield is a writer, editor and communications consultant for academic institutions, companies and non-profits in the life sciences. He is based in Camarillo, California. Follow @AMPorterfield on Twitter.