Farmers care about three things: yield, yield and yield.

–Agricultural consultant, California

We simply can’t continue to produce food far into the future without taking care of our soils, water and biodiversity

–Claire Kremen, co-director, Berkeley Food Institute

If we’re going to feed the world, we will need to grow a lot of food. The global population is expected to grow to 9.7 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100, according to the United Nations with roughly half of the growth taking place in Africa. The UN predicts that by 2050 the human race will require 60 percent more food—100 percent more in the developing world.

How do we meet those needs? Organic farmers say we can get there using agroecological practices, and preserve the increasingly fragile environment in the process. But conventional farmers say, that’s a fools promise. Organic farming simply can’t match the yields of conventional farming. And so far, most studies have shown a sizable “yield gap,” particularly for key staple crops such as wheat, soybean and corn. These gaps have been estimated as low as 10 percent and as high 50 percent or more. One recent study estimated the shortfall at 35 percent in corn; 31 percent for soybeans; and 45 percent for cotton, a key commodity crop for clothing and other uses.

Organic advocates fire back: Yield isn’t everything they say; increasing yield while degrading the soil will end up backfiring. They say higher yields come with an environmental price and cannot be sustained forever because they are dependent on the use of synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, which they claim strip the land of its vitality. They raise questions about the sustainability of genetically modified crops, which because they are often paired with pesticides, deplete the soil, creating the potential for future food shortages. Organic advocates like Mark Smallwood, executive director of the Rodale Institute, argue that organics are better for the soil—‘soil health is critical and building it is the only way to “leave more resources for future generations.”’

The two sides have been entrenched, and sharing of practices and learning from each other is more a hope than a reality. Is there a way to bring these two groups, often antagonists, together?

To build a bridge, it’s important to establish data that both sides can confidently rely upon.

With that in mind, University of Wyoming weed scientist Andrew Kniss, agricultural consultant Steve Savage and University of Wyoming agroecological scientist Randa Jabbour looked carefully at data collected from more than 10,000 organic farmers, representing nearly 800,000 hectares of organic farm land. They crunched the data with U.S. Department of Agriculture numbers and found that while overall yields are higher with conventional methods, organic practices did have better yields in some crops and in some locations. They published their findings and the implications, in PLOS One.

The new study is valuable, said Kniss in a blog post on Biology Fortified, because of two significant differences from previous work:

- It looked at crop reports from actual farms, instead of at data from carefully controlled experiments, which don’t take into account issues like equipment, labor and production scales.

- It carefully matched USDA 2014 survey data for both organic and conventional farms, so that they were comparing the same crops in the same states.

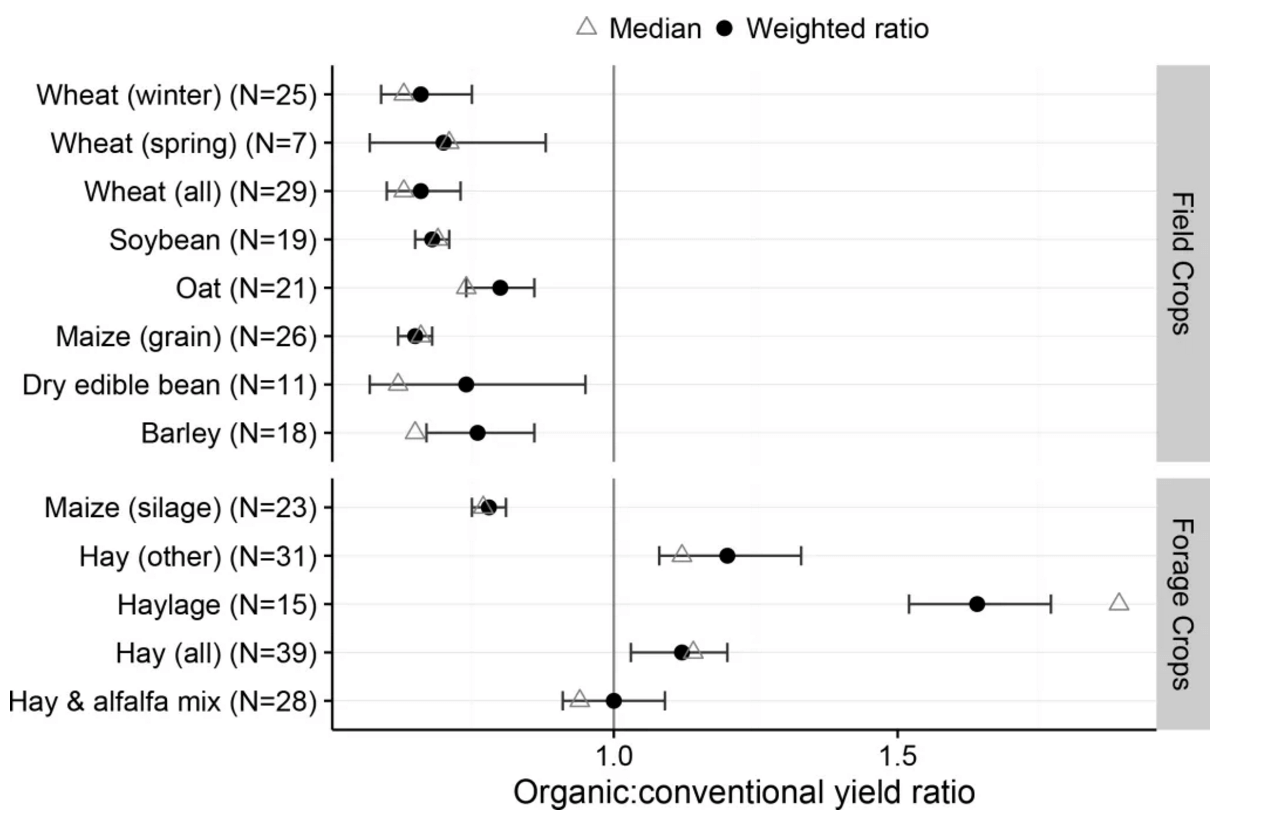

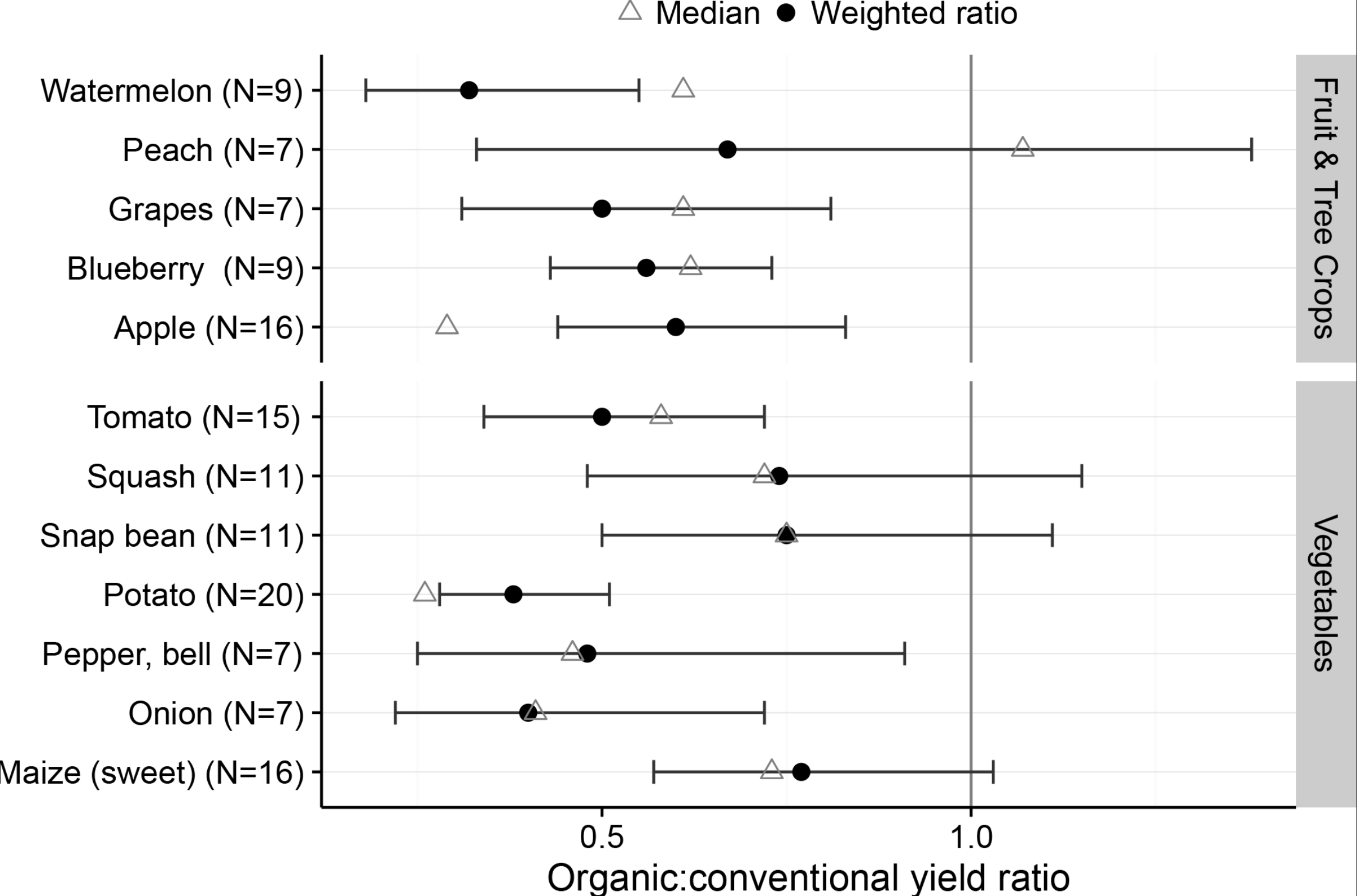

The USDA survey was based on data from a huge number of U.S. farms: 10,000 organic farmers, working on nearly two million acres, as well as from 83,000 conventional farmers. The study found that, similar to other studies, organic yields of row crops, including winter and spring wheat, soybean, oat, feed corn, edible dry beans and barley were all significantly lower than conventional yields. Organic farms produced roughly 1/3 less wheat and soybean, both important staple crops. Potato production on organic farms was a sizable 62 percent lower. And like some other work, feed grains such as organic hay and alfalfa were significantly higher. While other studies have shown similar results, this study was more definitive as it relied on real farming data.

When they got further into their data, they saw that organic yields of a few crops—squash, snap bean, sweet corn and peaches—were no different from conventional yields, and that some crops, like peaches, had significantly higher yields (figure below). Some locations had conventional farming yields ahead of organic farms, but not by very much.

There were four crops in certain geographic areas where organic farming accounted for more than half of the acreage dedicated to them. To Kniss and his team, this data suggested that organic farmers are doing something right, depending on the geographic area and crop. “There were a few states that were able to produce similar or even better yields with organic production compared to conventional,” he wrote.

For example, while dry bean yields were overall much lower for organic production, three states showed greater organic yields than conventional. Organic spring wheat in Colorado and sweet corn and squash in Oregon also out yielded their conventional counterparts.

Getting to why

Because of the size of their database, the team could not determine the reasons behind these differences in yields. And that’s the big question, which the researchers posed in their paper:

Could those same conventional producers not only improve yields but reduce their environmental impact? Or are some organic producers achieving high yields at the expense of the environment, depending on their water use and soil management?

Co-author Steve Savage, an agricultural consultant in San Diego, remains unconvinced that organic is the best answer for farming and the environment. But he does see an opening in shared technology and methods. In a draft manuscript he made available to the Genetic Literacy Project, he wrote:

Neither ‘organic’ nor ‘conventional’ are monolithic categories as both include a range of practices. However, conventional farmers are free to utilize all the good farming options allowed in organic, while having access to some useful ecological sensitive tools that fall into the ‘synthetic chemistry’ and ‘GMO’ categories, but are not available to organic farmers.

What are the environmental tradeoffs between organic and conventional/GMO systems in terms of pesticides, land-use-efficiency, soil building, water quality and greenhouse gas emissions?

Savage, who has an agricultural blog called Applied Mythology, told ACSH that it would be a “bad idea to expand organic to any great extent” because of the gap in crop yield.

That said, the three authors of this study, among others, would like to see an end to the entrenched debate. This study, Kniss said, was done in the hope that both sides could learn from each other. For some farmers, this can’t happen soon enough. Phoenix, Arizona, organic farmer Janna Anderson grows ancient and heirloom grains, and is constantly looking for different grains and traits. She also is a strong supporter of genetic modification. In an interview with the Arizona farm bureau, Anderson justified her support for modern crop biotechnology (even though she doesn’t use these techniques herself):

Biotech crops become a big advantage to everyone including the consumer. GMOs can reduce airborne pesticides, water pollution from run-off, increase yields, and generate drought resistant plants for the future and so much more. Additionally, GMOs can be very cost effective way to go and can target very specific pests rather than killing everything it touches like an aerial spray. Additionally, some GMO corn products utilize genetic engineering to insert BT, which is actually a product that is allowed in Certified Organic growing techniques.

A recent Genetic Literacy Project article featured a face off between two experts arguing in favor of and against organic farming; which practices are best to feed the growing world population? John Reganold, Regents professor of soil science and agroecology at Washington State University, said organics was superior, noting key sustainability practices: they were as productive; equal to or great in economic profitability for a farmer; and is more environmentally sound and socially just. In response, Bjorn Lomborg, director of the Copenhagen Consensus Center, said simply that organic farming is less efficient; if the U.S. were to switch to only organic to feed its populace, “it would mean we’d need to convert an area bigger than the size of California to farmland.”

According to Kniss, Savage and Jabbour, they’re both wrong. And right.

…agricultural systems should not be judged on yield alone. A primary goal for agriculture of the future should be to produce enough food to feed a growing population, and to do so while minimizing the negative impacts of that production. Organic agriculture has demonstrable benefits to the environment on a per unit area basis, however, those benefits are often negated or reversed on a per unit production basis because organic systems tend to yield less per area.

Farmers and consumers have to make difficult trade-off decisions involving economics and the environment. One size does not fit all.

Andrew Porterfield is a writer, editor and communications consultant for academic institutions, companies and non-profits in the life sciences. He is based in Camarillo, California. Follow @AMPorterfield on Twitter.