Editor’s Note: This is the second article in a three-part series exploring some common concerns heard about GMOs. The first part examined genetic engineering versus traditional breeding.

The use of herbicides and pesticides in modern farming may be the most misunderstood issue out there. Let’s try to reconnect it with reality a little bit. There are currently two major traits that GE crops have been bred for.

We’ll start with the second most common trait, the Bt trait. This has been bred mostly into corn and cotton, but is making it’s way into other crops as well. Corn borers and bollworms are two major pests for corn and cotton. These pests have been managed for decades with the organic pesticide Bt which is a soil bacteria which is poisonous to these insects. It’s important to understand the ‘mode of action’ through which Bt kills these insects. In fact, it’s important to understand the concept from toxicology of ‘mode of action’.

Mode of action is the way that a substance acts as a toxin. Most so-called poisons aren’t poisonous in a vague general way. They do something specific to their ‘targets’. The more specific, the better, because something can be very toxic to one organism and harmless to another.

Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) produces a protein (Cry protein) that when eaten by these bugs is activated by the alkaline environment of their digestive system and binds to a receptor there, paralyzing the digestive system.

The reason this insecticide is so safe is because the mode of action is specific to the target pests. Humans and other mammals have acidic digestive systems, so the protein is broken down in our digestive systems and we don’t have a receptor for it to bind to and paralyze our digestive system. It’s just another protein.

Breeding corn or cotton to express the Cry proteins has an added advantage for the environment. Not only is it harmless to critters without the necessary receptor, but it only kills bugs that eat the plant and leaves other bugs alone, while spraying with Bt can kill some bugs that don’t pose a threat to the crop.

The adoption of the Bt trait in corn and cotton has meant a massive reduction in the amount of soil applied insecticides applied by conventional farmers. (Yes, there is some resistance to Bt developing in insects in some parts of the country and farmers are falling back on some of those insecticides. This is a standard pest management issue and its not clear why this should be seen as making the case against using these crops in the first place.)

Let’s look at two charts the first taken from the journal Science based on USDA data.

The second drawn from a study that looked at insecticide traces found in air samples.

Raise your hand if you want to go back to the profile of insecticide use from 1995, the year before the first genetically engineered corn hit the market.

By the way, lots of plant produce their own insecticides. The idea for Bt crops came from nature. In fact, 99.99% of pesticide ‘residues’ in your diet were produced by the plants themselves, naturally.

‘Drenching crops in toxic herbicides‘

What we are talking about here is herbicide resistant crops, most notably Monsanto’s RoundUp Ready crops. These have been bred so that they don’t die when the herbicide RoundUp (glyphosate) is applied to the fields to kill weeds. The reason that RoundUp was chosen is that it is much more effective than other herbicides while being relatively non-toxic and easy on the environment IN COMPARISON to other herbicides. In fact, for acute toxicity, RoundUp is less toxic to mammals than table salt or caffeine. Again, this has to do with ‘mode of action’. The reason it is incredibly effective as an herbicide is also the reason it isn’t a poison to mammals.

Glyphosate works by inhibiting a metabolic pathway that only plants and bacteria have. For critters that don’t have the shikimate pathway, it is just another salt with the normal toxicity of salt (less than sodium chloride). If you are a plant that relies the shikimate pathway for converting light into energy, it’s literally ‘lights out’.

So while use of glyphosate is up, use of other more problematic herbicides is down. It works so well that it allowed many farmers to adopt what is known as conservation tillage. Tillage is an important tool for controlling weeds. Prior to planting the farmer tills the soil to interrupt weeds which would cause problems during the growing season. While this may seem like a good way of avoiding using herbicides, it releases lots of carbon into the atmosphere, uses plenty of tractor fuel and cause problems with erosion and soil structure. The judicious use of a low environmental impact herbicide like glyphosate is often the environmentally friendlier strategy.

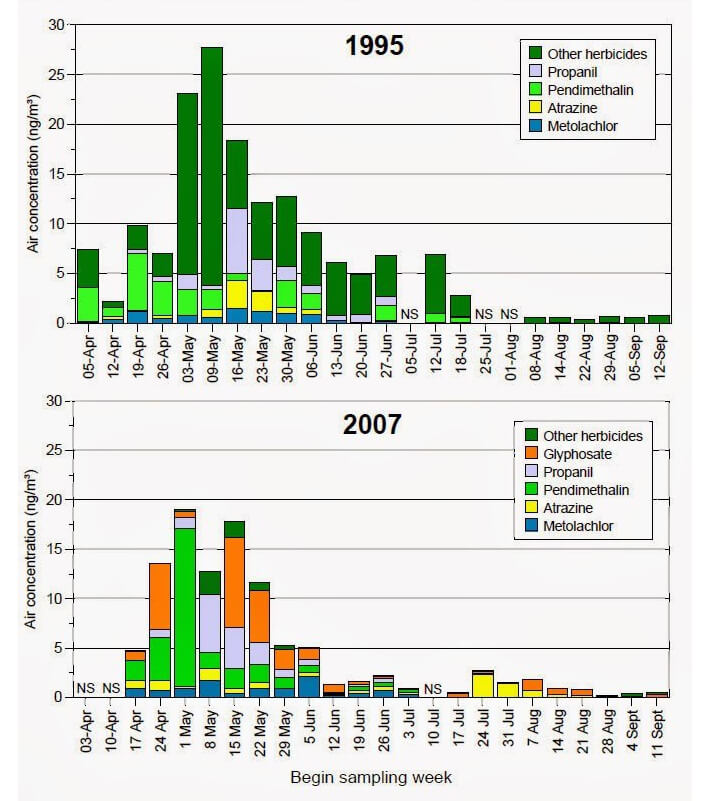

Consider this chart taken from the same study showing trace amounts of herbicides in air samples. Again, a show of hands if you’d like to return to the 1995 herbicide profile (keeping in mind that the category of ‘other herbicides’ that have fallen out of favor nearly universally had a higher environmental impact).

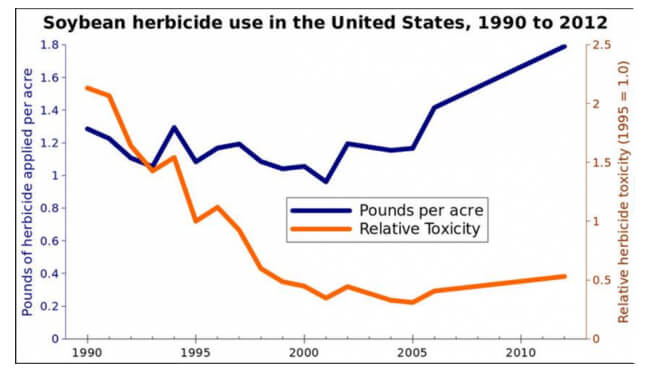

While it’s true that while remaining mostly flat, with a recent trend upward in terms of the amount of herbicide per acre measured by weight, because the shift has been to less impactful herbicides, the net effect has been lower environmental impacts due to herbicide use.

While it’s true that while remaining mostly flat, with a recent trend upward in terms of the amount of herbicide per acre measured by weight, because the shift has been to less impactful herbicides, the net effect has been lower environmental impacts due to herbicide use.

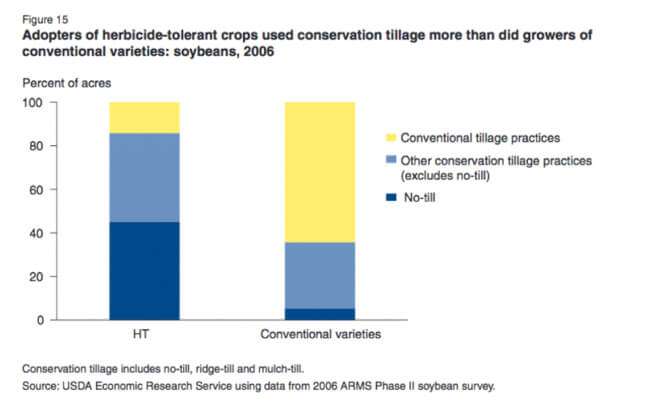

In addition, it’s important to realize that herbicide tolerant crops have facilitated the shift on thousands of farms and millions of acres from using tillage to help control weeds to the much more environmentally friendly methods of no-till and conservation tillage. Farmers till their fields to break up the growth of weeds, but tilling also disturbs soil structure and leaves soil exposed to wind and rain erosion as well as releasing carbon into the climate. Here is a comparison of the tillage practice of GE soy adopters and non-adopters.

We should also address what we mean when we say “drenched in herbicides”. Lucky for us, Kevin Folta has done the math.

An acre is 4047 square (meters). That means 83 milligrams per square meter. My 7th grade science teacher Mr. Herzing said, “A milligram is about the weight of an insect wing.” Wow, that seems like not much! But how much soybeans does that get ya? Soybean yields in 2013 were 43.3 bu/acre and a bushel weighs 60 lbs, so that’s about 2598 lbs/acre, or 1180 kg/acre. To make it relatable to herbicide used, we need to get it down to square meters. That’s 291 g soybeans per square meter. So 83 mg of active ingredient is needed to produce 291 g (0.640 lbs) soybeans. Of course these numbers assume one application, which is likely not the case, but it still is a tiny amount.

Before we move on, I’m sure that some of our readers are starting to rumble about so-called ‘superweeds’. Superweeds is a sensationalized term for weeds that develop resistance to the strategies meant to control them. What you need to understand is the same thing with Bt resistant insects. If the RoundUp Ready strategy is overused, you end up back close to square one, except you’ve gotten a decade of reduced environmental impacts and now you have to change up your game a bit, using some of the tools you would have used if you didn’t have RR crops.

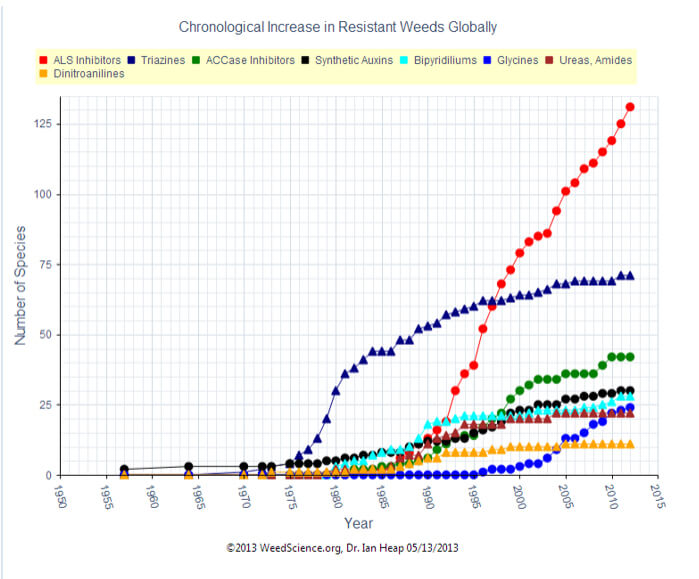

Herbicide resistance is hardly unique to glyphosate. In fact it’s a much bigger problem for other categories of herbicides, but you never hear about that because people are just looking for something to write about and anything with GMOs makes for great reading (I get the irony here.)

If you want to talk about ‘superweeds’ and glyphosate and the role of GE crops, first let’s talk about ALS inhibitors, trianzines and ACCase inhibitors and then you can tell me how GE crops ‘create superweeds’. Look at those steep curves where each of those other herbicides was out-evolved by weeds, and then look at the rate for glycines and consider the massive amount of acreage they are used on. Glyphosate is actually pretty miraculous in its ability to thwart weeds without developing resistance. I’m sorry, but the ‘GE crops create superweeds’ story doesn’t hold water. What causes resistance is over-reliance on a single strategy, which isn’t specific to GE crops, as demonstrated by the cases of those other herbicides, with their much greater numbers of resistant weeds.

A section of this article previously appeared on Food and Farm Discussion Lab under the title “3 Most Common Internet Objections to GMOs” and has been republished with permission from the author.

Marc Brazeau is a writer on food and agriculture. He blogs at Food and Farm Discussion Lab. Follow Marc on Twitter @realfoodorg.