Indeed, our growing understanding of how memories are formed is pushing us toward a day when we’ll be able to scrub disturbing memories from our minds, or even replace them with experiences and skills that would normally take years to learn.

The television episode deals with what happens after the USS Enterprise encounters an alien probe in deep space, Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart) finds himself on a planet with a humanoid civilization known to have gone extinct 1,000 years earlier. The starship commander spends some six decades in his new environment, gradually embracing his new life. He becomes a community leader, a father and grandfather, and a virtuoso on the native flute. Over time, he mourns the death of a close friend and then his wife. He also copes with the reality that the planet’s changing climate will deny his grandchildren a full life. None of this, however, is real.

After seeing a space probe launch — the very probe that the Enterprise encountered in space — Picard wakes up on the Enterprise bridge. What felt like 60 years in Picard’s mind actually transpired over the course of just 25 minutes, during which he appeared to be in coma. The probe was carrying a rather unique message — it consisted of the experience of being part of the dying civilization.

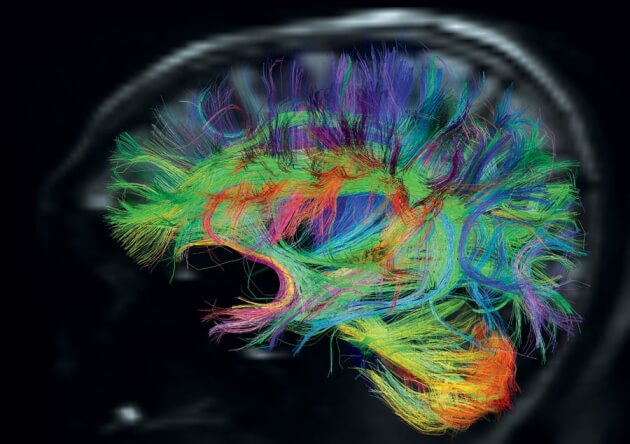

Neural interface technology had packed 60 years-worth of experiences into Picard’s brain, and not just images of people and events. Inside the probe was a Kataanian flute, and Picard was able to play it with the expertise that he had developed in his simulated life. Imagine getting an upload of a new talent or skill into your brain as easily as uploading a computer file.

Science fiction to reality

Could we develop a similar capability? That may depend heavily upon a handful of ambitious attempts at brain-computer interfacing. But science is moving in baby steps with other tactics in both laboratory animals and humans.

Thus far, there have been some notable achievements in rodent experiments, that haven’t done so well with humans. We don’t have a beam that can go into your mind and give you 60 years worth of new experiences. Nevertheless, the emerging picture is that the physical basis of memory is understandable to the point that we should be able to intervene — both in producing and eliminating specific memories.

At MIT’s Center for Neural Circuit Genetics, for example, scientists have modified memories in mice using an optogenetic interface. This technology involves genetic modification of tissues, in this case within the brain, to express proteins that respond to light. Triggered by implants that deliver laser beams, brain cells can be triggered to be more or less active. In research that has been published in the prestigious journal Nature, the MIT team used the approach in specific brain circuits important to memory consolidation. The researchers were able to enhance the development of negative memories — for instance a shock given to an animal’s leg — and also to convert those negative memories into positive memories. The latter was achieved by letting male mice enjoy some time with females, while nerve cells that usually deliver the negative impulses associated with the former shock were stimulated through the optogenetic interface.

In humans, work with memory modification has involved N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which function like little doors for positive ions to move through the membranes that surround neurons. NMDA receptors are affected by glutamate, a neurotransmitter whose effect on the NMDA receptors is enhanced by an antiobiotic called D-cycloserine (DCS). When this happens in an area of the brain called the amygdala, memory consolidation (the stabilization of newly developing memories) is strengthened. Researchers have thus found that DCS can increase effectiveness of what’s called exposure therapy, if given within a few hours before commencement of each therapy session. Used to treat anxiety disorders, exposure therapy involves the intentional exposure of patients to the thing that provokes their anxiety. If you fear snakes, for example, the therapist will show you a snake, from a distance at first. Eventually, you will be asked to hold the snake. The implication of the research is that DCS improves the learning that removes the anxiety in exposure therapy, which also should have implications for other therapies that work based on learning and formation of new memories and associations

Theoretically, [DCS should] facilitate learning processes, so if you can use it to facilitate extinction learning, that’s got fantastic clinical implications,” noted Mark Bouton, PhD, a University of Vermont professor of psychology was quoted in a review from the American Psychological Association.

But using drugs like DCS could be really tricky, requiring precise adherence to very specific timing and dosage that could vary significantly depending on the clinical setting and even between patients. A 2012 study, for example, on patients with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) found that DCS actually made things worse.

The same is true when researchers try to exert the opposite effect on memory by way of the NMDA receptors, namely blunt memory consolidation. The agent under study in this case is xenon gas, an anesthetic used in humans. When given to laboratory animals within an hour after after a traumatic event, xenon blocks the memory consolidation that can lead to long-term trauma equivalent to PTSD in humans. Exercise and nutritional factors also play roles in blocking the processes that make psychological trauma worse.

So what we have here is an immature, but real, tool bag of agents that can help and inhibit formation of long-term memory. But it is very incomplete and must work in concert with outside factors — including psychotherapy or the experiences of one’s life. Still, given the rapid development of virtual reality technology — it’s not hard to see that supplying the outer stimuli — we may very well be moving toward a time when we’re able to manage the brain’s memories.

A version of this article previously appeared on the GLP on August 8, 2017.

David Warmflash is an astrobiologist, physician and science writer. BIO. Follow him on Twitter @CosmicEvolution