What if we could fix a kid’s genetic disease, cure them for their lifetime? What if we make that for all of their children, forever? Or enhance humans to be genetically better? What’s your opinion of gene editing and enhancement?

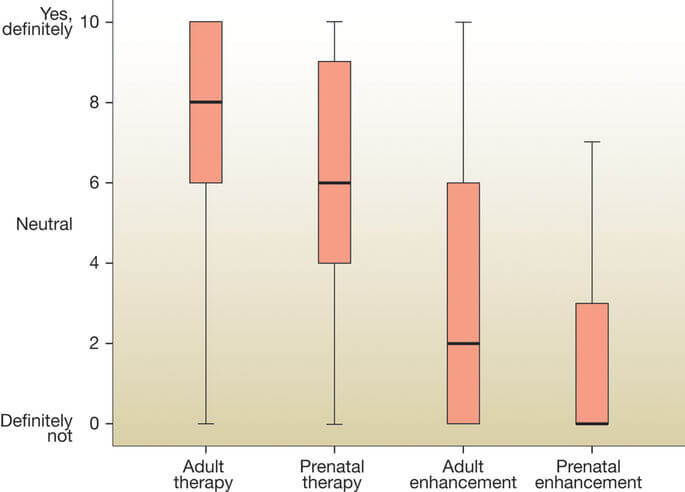

A survey asked what people thought. Participants gave a green light for adult gene therapy. They were cautious about embryo gene therapy, and disfavoured gene editing for enhancements. Do my readers feel the same way? What do you think legislation say?

Surveys and demographics can help develop policy by learning what people think. It can help prevent the views of vocal minorities being over-represented.*

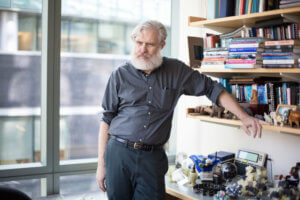

Important, too, is the advice of experts. Policy by popularity alone isn’t necessarily ‘right’ or best for people. (Never mind policy by loudest voice!) Towards the end of this article I look at some suggestions made by geneticist George Church.

The survey

People from 10 European nations and from the USA gave their moral views on gene editing. The survey tested two contexts—gene therapy and genetic enhancement—over two categories—prenatal and adult.

Participants recorded if they thought the person did the morally correct thing, and if they would have done the same. Scores ranged from 0 to 10, with 10 being strong approval. The researchers also collected written comments.

Successful gene therapy in an embryo lasts not only the life time of the yet-to-be-born kid, but is carried on into their children’s DNA. Gene therapy after birth could last that person’s lifetime, but would not be in their children’s DNA.

Mutations are changes in our DNA. The key thing is that they cause a change, not that they are ‘bad’ or weird. We can blame cheap science fiction for that idea! Most mutations do nothing. Some break stuff, sometimes in tiny ways, sometimes in bigger ways. Some of these mutations cause genetic disease. A few (rare) mutations are beneficial, and actually add abilities. Gene therapy changes mutations that cause genetic disease back to the DNA sequence found in people without the genetic disease.

Enhancements, if we were to do them, would be mutations (changes to our DNA) that gave the person something more than what they would otherwise be. The big, sweeping things reported in breathless media reports are mostly fantasy; realistic options are small, focused things. I imagine early targets will be the very rare mutations that cause beneficial mutations in a few people.

What do people think?

Here’s the key graph from Public views on gene editing and its uses,

Survey participants indicated they approved of gene therapy in adults. They were a little less certain for prenatal gene editing, mostly against editing adults for ‘enhancement’, and strongly against editing prenatal embryos for enhancement. The median scores for enhancement were low, 2 for adults and 0 (zero) for embryos.

The researchers report that:

More than half of the sample in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and the UK say they would not use gene editing for prenatal enhancement. This pattern is also seen in Austria, Denmark and Germany for adult enhancement.

The range of responses for all the options were wide. With the exception of embryo enhancement, at least some people were strongly against it, and some strongly for it.

Most of the people surveyed gave scores of 8 or higher for gene therapy for adults, suggesting most of the public thinks this should continue.

People disfavoured gene enhancement in adults. That said, the range of responses is quite wide. This suggests a sizeable minority were neutral or in favour of it.

People strongly disfavoured embryo enhancement. No-one at all was strongly in favour of it, unlike all the other three situations.

The worded comments people added showed a similar pattern. The researchers divided these into 21 categories, listed in the Footnotes below.**

A caution

The survey article ends with a caution:

A final word on the value of surveys in this controversial territory. Public opinion cannot and should not tell us what is right to do.

Essentially this is a warning not to use ‘the argument from popularity’ fallacy: just because something is popular, does not mean it is ‘right’ or even in the best interests of the people in favour of it. Something unpopular may be ‘right’ or better for people.

Evidence-based research can inform what might be best to do. Hence the need for science commissions, professional working groups, and similar.

Surveys of opinions can help. They might tell you if a previous objections have moved on, for example. One example of this in New Zealand might be a survey indicating that public opinion about the safety of GM food has changed.

Some thoughts

One concern is that the study categories did not include kids or infants, at least not by name. Gene therapy would often aim to often treat the young, at earlier stages of their disease (and with more to live for). It would have been good if this were covered more explicitly or directly.

Most people were neutral or cautiously supported prenatal therapy, but some indicated they were unsure about it or against it. It would be useful to know why some people have reservations. Some medical conditions are likely to be best treated as early as is possible. For some it may be the only opportunity to treat them. Is more communication of why prenatal gene therapy can be helpful needed?

It would interesting to know if there are any thresholds for these views. For example, do people’s thoughts parallel Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee’s? (Paraphrased in SciCurious’ live-tweet of a panel discussion with him and Eric Nestler):

If we are going to intervene genetically in the germline, there has to be a threshold of extraordinary suffering.

The special issue this survey paper occurs within also covers so-called ‘three-parent babies’, the ‘14-day rule’, and wider issues. In my opinion embryo screening is too often left out of these discussions despite that it’s a way we can avoid some serious genetic conditions. Similarly, there may be other ways to tackle some disorders (stem cell treatment, for example). Gene editing is not the only game in town.

George Church’s thoughts on embryo enhancement

We might not favour genetic enhancement, but well-known(and out-spoken) geneticist George Church thinks we should consider when to use it. He essentially rallies against a sweeping ‘ban’, encouraging people to think about options within the option of genetic enhancement.

Church notes the scientific bodies did not recommend a ‘pause’. They suggested basic research develop a better understanding first. In time this understanding would allow trials under controlled circumstances:

A June 2015 report from the Congressional Subcommittee on Research and Technology claimed that “an April editorial in Science Magazine called for a prudent path forward for genomic engineering. It recommended a moratorium on further research.” The cited article, however, did not include the word “moratorium” (or “ban” or “pause”). Moreover, a recent report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) concluded that “germline genome-editing research trials might be permitted, but only following much more research aimed at meeting existing risk/ benefit standards for authorizing clinical trials and even then, only for compelling reasons and under strict oversight.”

Church suggests pausing out of fear of unknown risks mostly delays medical advances for little sound gain:

Doing nothing merely for fear of unknown risks is itself risky — greatly restricting the advance of medicine. It may seem tempting to draw a line for permissible gene editing at some qualitative or quantum step such as “germline versus soma” or “enhancement versus basic health,” but the reality is that we often regulate practices on the basis of ethical costs and benefits at specified points along a continuum — for example, speed limits, blood alcohol levels, and age limits.

Genetic enhancements

He suggests we should be wary of ‘banning’ enhancements:

The issue for many critics lies not in enhancement relative to our ancestors, but rather relative to one another. We should study cases in which technologies are equitably distributed to all 7.5 billion of us, such as the extinction of smallpox and polio through global enhancement of immunity.

My read is that he doesn’t want to see a ‘ban’ on enhancements. He believes the real issues are not with (approved) enhancements, but with the equal opportunity to access to enhancements. If the enhancement is of benefit to everyone, and available to everyone, perhaps we should consider it.

It is a topic worth exploring. There has been a lot discussion on this, especially from those interested in the ethical and legal aspects of gene editing. Some responses to Church’s suggestions can be found online, for example in these Twitter threads.

Worth remembering is that gene enhancements or therapies for a long time to come will be for small, focused things, not the big sweeping things we often see in media stories. It’s one reason why scientists have focused on rare diseases. Aside from clearer ethics, their cause is often changes in just one gene in a simple well-understood way. Sometime in the (distant) future we might be able to tackle complex things involving many genes, but they’re not possible now or the near future.

Worth remembering is that gene enhancements or therapies for a long time to come will be for small, focused things, not the big sweeping things we often see in media stories. It’s one reason why scientists have focused on rare diseases. Aside from clearer ethics, their cause is often changes in just one gene in a simple well-understood way. Sometime in the (distant) future we might be able to tackle complex things involving many genes, but they’re not possible now or the near future.

Footnotes

(Footnotes indexed from the text using asterix are in the next subsection.)

I would like to have seen the distribution of scores plotted, rather than just a box and whisker plot. This would make for a ‘noisier’ graph, but it would give a better idea of the distribution of the scores. Is there a very tight median? Does there look to be a bimodal distribution? And so on.

I’ve used the terms ‘gene editing’ and ‘gene therapy’. Others would argue that ‘genome editing’ is more accurate, and that it’s a different thing to ‘gene therapy’. I’ve taken my lead from the survey article, and that, in general, people are more interested in the outcome than the details of how the work was done.

Explaining more about the techniques and applications would take entire articles (or a series of them). If readers are interested in this, let me know.

On a more personal note, I have been distracted from starting a series on gene therapy by illness, then other projects. Perhaps this piece might get me back on track. I can hope…? (Feeling shut out of paid writing didn’t help. If you know an editor that would like a story related to molecular genetics or similar, let me know!)

Indexed notes

* Demographics may help develop policy for other contentious issues. Some issues are dominated by a few overly vocal voices, with the middle ground barely represented. Formal submissions for government review are also likely to be views from those with interests or extreme views. Surveys can try to see the full picture, and give context.

** Worded response categories identified:

- 1—Support – unqualified statement

- 2—Support mentioning therapy, improving quality of life

- 3—Support mentioning safety/ benefits outweigh risks

- 4—Support mentioning natural for self/parents to want best

- 5—Support mentioning autonomy/ individual choice

- Uncertain, can’t decide

- Wrong – unqualified

- Immoral, unethical

- No need – normal or average OK

- Only used for diseases

- Unlikely to work – low efficacy

- Playing god, unnatural, messing with nature, accept fate

- GM wrong, non-reversible, against evolution

- Risks, unknown unintended consequences

- Designer babies, master race, Nazis, Frankenstein

- Obtaining an unfair advantage

- Parents have no right to impose on child

- Increase social disparities

- Would be abused/doping

- Undermines character, improvement from effort not drugs

- Other

Grant Jacobs is a computational biologist based in Dunedin, New Zealand. Find him on Twitter @BioinfoTools.

This article originally appeared at Jacobs’ Code for life bog at Sciblogs as Public opinion of gene editing and enhancement and has been republished here with permission.