Many critics see GERA as an effort by anti-GMO activists to block foreign multinationals from involvement in Uganda’s agro-biotech industry. But local researchers, innovators and biotech scientists say they will suffer more.

What’s most disturbing about the act is what’s known as clause 35, which deals with liability issues. In the event that there is any harm to the environment or human health, the act presumes guilt for any person or company holding a patent for the genetically engineered product accused of causing the problem.

Currently in Uganda, the public agricultural research institutions undertaking biotech crop research are: the state-owned National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO) and public universities, under the National Agricultural Research Systems (NARS) policy, NARS Act (2005) and the National Biotechnology and Biosafety Policy (2008).

In 2013, the government introduced in Parliament the National Biotechnology and Biosafety Bill. It took four years for legislators to approve the measure, which was then refused by the president. This was after activists—many of them with close ties to his office—contested it, fearing it favored commercialization of GM-crops they had long misrepresented as “harmful, enslaving and risky.” The 2017 measure included a fault-based liability provision, whereas the newer law uses a strict liability standard.

Clet Wandui-Masiga, founding chief executive officer of the Tropical Research Institute for Development Innovations, told the Genetic Literacy Project that blockage of GM-crops is not about harm or risk anymore—with those concerns debunked by global consensus of reputable scientific institutions. But blockage is about ensuring that farmers do not discover that the technology is safe and effective. The analyst said:

The activists also deal in farmers’ misery like presenting proposals to the West, to fund programs and projects to fight famine, hunger and starvation as a result of loss of crops to drought, diseases and pests. So when GM-technology helps to reduce these challenges, activists fear loss of funding. They fear to close shop because scientists would have managed the challenges.

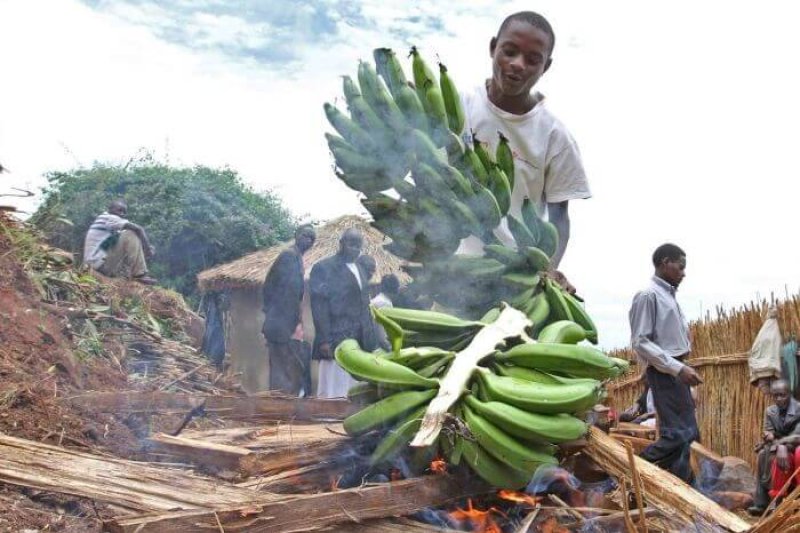

Uganda is home to the highest number of GM-based agro-research projects on the African continent, with the oldest being: Bt-cotton/Ht-cotton; bananas resistant to banana bacterial wilt (BBW) disease and banana biofortified with beta-carotene [Vit. A enhancement]; the twin-Drought-Tolerant (DT) and Insect-Resistant (IR) maize under ex-WEMA now named TELA, and cassava resistant to the lethal twin-viral Cassava Brown Streak (CBSD)/Cassava Mosaic Disease (CM) Diseases.

Wandui-Masiga, a geneticist and agricultural entrepreneur, lashed out at Clause 35, noting that professional viewpoints were largely ignored in the new law.

“But activists completely blinded top officials in the ruling class and in Parliament, to believe that we should legislate against foreign interests via this law, instead of an enabling legislation to regulate and allow access to a good technology,” Wandui-Masiga said.

A few days before passage of the GERA, professor Joseph Obua, chairman of NARO’s Governing Council, urged legislators to reject the strict liability clause and consider adoption of a fault-based liability rule. He argued that the measure threatens to criminalize scientists who are simply carrying out research and commercialization of GM crops. In a recent commentary published in the State-owned New Vision newspaper, Obua said:

There are existing legislations with liability regimes for managing other plant breeding methods and these don’t provide strict liability for errors and commissions.

Mzee Swizen Wamala, an influential large-scale farmer in midwestern Uganda has been waiting anxiously for new GMO crops to be released by the government. He wants to plant BBW-resistant GM bananas and DT/Stem-borer-resistant Bt-maize on his 300-acre farm. Who knows GM crops better than our scientists in NARO?” he asked. In a recent interview, he said:

If that law will block farmers accessing the better-technologies we saw in NARO, His Excellency the President shouldn’t sign it as passed by parliament. He should ask Parliament to improve it, to enable GM-technologies be accessed as per farmers’ needs and interests.

The new strict liability measure in Uganda’s legal system was last amended in the Ethiopian decree on biotechnology and genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and many observers are wondering why Uganda is looking to Ethiopia for guidance. Particularly when you consider that Uganda has a bigger technical capacity in infrastructure, manpower and a longer experience researching GM crops.

Since early 2000s, public education and awareness on biotech and GM-crops has been carried out by groups that include the state-owned NARO; the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology; and the Uganda Biotechnology and Biosafety Consortium (UBBC), an umbrella body of biotech stakeholders.

But despite the efforts made by these groups, and others, the passage of this new law could mark an uncertain turning-point for advancement of a science-based biotech research and development.

NARO scientists have described GERA as an emotion- and fear-driven measure:

It’s going to kill the spirit and interest in areas like gene-discovery and innovation of genetically-modified/engineered (GM/E) products to solve constraints and improve farmers’ economic gain via more robust crop-technologies.

Scientists and ally-MPs have been in the trenches for many decades, battling against a swam of Euro-funded activists working to sow distrust of GMOs among members of the public. They have argued that GMOs are hazardous, carcinogenic, capable of causing sterility/infertility in women, impotence in men, and are responsible for a litany of negative impacts on the environment.

Those fear-based arguments appear to have persuaded lawmakers, under the chairmanship of Deputy Speaker Jacob Oulanya, to pass such an unfriendly piece of legislation. This after years of arguments and counter-arguments between scientists for and against adoption of GM-crops. Up until the afternoon of November 28, the pro-GM technology group negotiated for legislation of a fault-based liability rules

Even a few hours before passage of the new law, the pro-biotech coalition and the minister for science, technology and innovations – Dr. Elioda Tumwesigye — floated a new compromise position for a dual fault-based and strict liability law. But the anti-GMO group dug in, driven by its fear and of multinational and private company interests they allege want to invest in the discovery/innovative development of patented GM-crop & animal technologies. And that’s what carried the day in Parliament.

Peter Wamboga-Mugirya is a Ugandan freelance science journalist, with a focus on agricultural, energy, environmental, health and food security issues. Follow him on Twitter @wambotwit