When I first learned about genetically modified food in the mid-1990s, I thought it was nothing more than the next step in the application of science to plant breeding. After all, humans have been genetically modifying food for thousands of years through the processes of selecting for traits, hybridization, crossbreeding, grafting, marker assisted breeding and mutagenesis. As a result, the crops we grow and consume today look and taste nothing like the crops grown hundreds or thousands of years ago.

Seedless watermelons and grapes (developed in a laboratory) and sweet red grapefruits (mutants created through radiation) are examples of how food has been genetically modified through the ages. Plumcots, tayberries, blood limes, tangelos and limequats are all examples of hybrids of two or more fruits created by cross pollination. The application of modern biotechnology processes to agriculture such as the transfer of genes between species is simply a more precise and faster method of genetically modifying food to get outcomes — such as disease-, insect- and drought-resistance — than the methods previously utilized.

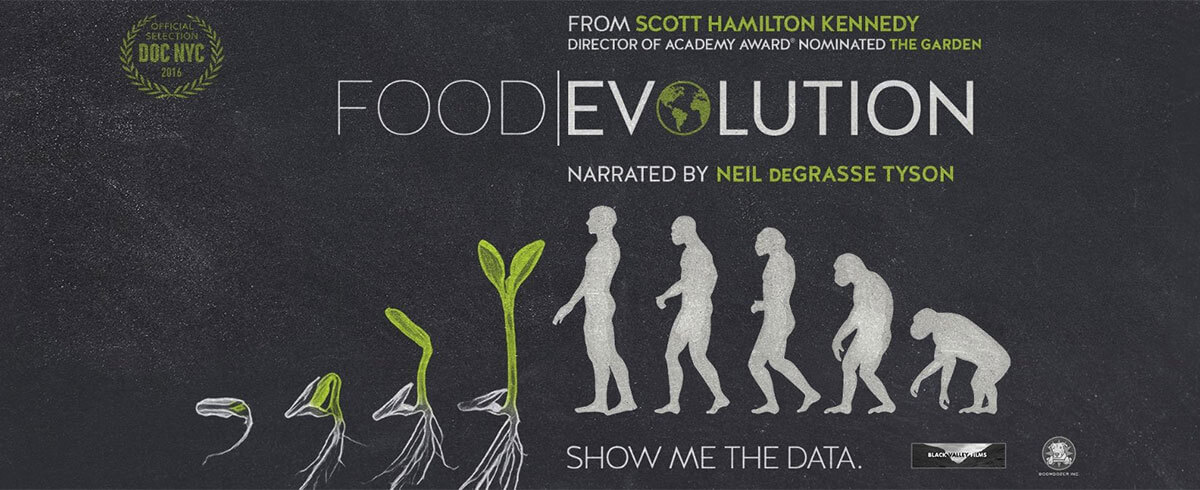

I was therefore quite astonished to learn of the vocal demonization and vilification of GE foods by opponents who ascribed all sorts of dangers to them — none of which were validated by scientific evidence. This chasm between the supporters of GE foods and their opponents is highlighted in the 2017 documentary “Food Evolution,” which the producers hoped would calm the debate and boost public support for a technology that holds great potential to grow food that is disease- and drought-resistant and more nutritious for a world population estimated to grow to 9.7 billion by 2050.

While the film was effective in changing some people’s minds about the supposed dangers of GM food, its distribution was too limited to significantly change the terms of the debate. For example, in New York City. where I saw the film, it played in one theatre for just one week. When I saw it on the first showing on a Friday morning there were just two people, including me, in attendance.

While the film was effective in changing some people’s minds about the supposed dangers of GM food, its distribution was too limited to significantly change the terms of the debate. For example, in New York City. where I saw the film, it played in one theatre for just one week. When I saw it on the first showing on a Friday morning there were just two people, including me, in attendance.

Even though the film reached a relatively modest audience, the pushback from the anti-GMO forces was strong — an indication of how threatened they feel by the objective science presented. In a Huffington Post article, Stacy Malkan, the co-director of the US Right to Know, wrote:

The film… claims to offer an objective look at the debate over genetically engineered foods, but with its skewed presentation of science and data, it comes off looking more like a textbook case of corporate propaganda for the agrichemical industry and its GMO crops.

The anti-GMO Food First website called it “a well thought out piece of propaganda designed to manufacture public support for GMOs, while discrediting environmentalists, dissenting scientists, and organic farming.”

Enviro.news was equally harsh:

A new documentary film that claims to set the record straight on genetically-modified organisms (GMOs) has been exposed as a propaganda piece that aims for nothing more than to advance the agenda of chemical and biotechnology companies. Narrated by fake science icon Neil deGrasse Tyson, Food Evolution is backed and funded by a who’s who list of some of the most outspoken industry shills and violent psychopaths who will stop at nothing to spread more of their poison throughout the world.

Although the film did a good job of presenting the science, it also left me feeling that the gulf between the science supporters and the vast majority of opponents of GMOs, some of whom voiced their objections to the technology in the documentary, can never be narrowed.

For the scientific community this is a debate about the merits of the science and therefore scientists are eager to put forth their evidence. More than 275 of the world’s most prestigious science organizations have publicly stated that GMOs do not present a danger to human and animal health or the environment. That includes the US National Academy of Sciences and of its counterparts in Europe, Latin America and Asia.

The World Health Organization has also endorsed the safety of GMO foods, writing:

GM foods currently available on the international market have passed safety assessments and are not likely to present risks for human health. In addition, no effects on human health have been shown as a result of the consumption of such goods by the general population in the countries where they have been approved.

While GMO opponents claim there is a dearth of studies that prove the safety of GMOs, there are actually many studies that indicate they are safe. In 2013, an Italian meta-study catalogued and analyzed 1,783 studies addressing the safety and environmental impact of GMOs. The researchers could not find a credible example of research demonstrating that GM foods pose harm to humans or animals. It also could not find evidence that approved GMOs have introduced any unique allergens or toxins into the food supply — one of the central claims of opponents.

To the frustration of scientists, the broad consensus in the scientific community supporting the safety of GMOs does not satisfy critics. That is because for them this is not a debate about science. They cannot cite studies published in established peer-reviewed journals that indicate GMOs are harmful to human health because there aren’t any. Instead, they rely on scare tactics to promote their views, well aware that it is easier to frighten people than it is to reassure them.

To the opponents of GMOs, this is a struggle not about the science, but about values. They see GMOs as a symbol of what they believe modern agriculture and our global food distribution system represents: large scale, intensive farming, the use of pesticides and herbicides, monoculture crops, the pervasiveness of fast food, chemical additives used in food processing and their belief that large multinational companies monopolize the growing and distribution of our food. Monsanto, which is the target of much of the ire against GMOs acts as a metaphor for their opposition to agribusiness and the way we grow much of our food.

To the opponents of GMOs, this is a struggle not about the science, but about values. They see GMOs as a symbol of what they believe modern agriculture and our global food distribution system represents: large scale, intensive farming, the use of pesticides and herbicides, monoculture crops, the pervasiveness of fast food, chemical additives used in food processing and their belief that large multinational companies monopolize the growing and distribution of our food. Monsanto, which is the target of much of the ire against GMOs acts as a metaphor for their opposition to agribusiness and the way we grow much of our food.

Opposition to GMOs also reflects a deep suspicion of science, which many GMO opponents distrust because they think it is a ‘tool of corporate interests’. As a result, many scientists engaged in genetic crop research are labeled as shills for agribusiness in an attempt to demean and question their intellectual integrity.

Opponents of GMOs also argue that GMOs are not natural. But the reality is that none of the food we eat is in its natural state. If it was, much of the food we consume would be inedible and of very low nutritional value. Only by the manipulation of genes through various plant breeding techniques have we been able to develop a wide variety of tasty and nutritious foods.

It is doubtful that the strong scientific consensus in favor of GM crops will ever sway opponents. For many people, opposition to genetic engineering has become as much a part of their identity as the clothes they wear, the neighborhoods they live in and their religious and political affiliations. In effect, they have invested so much of their intellectual capital in their position that it has become a sunk cost they simply cannot walk away from.

We seem to live in a society in which many people believe they have a right to pick and choose the aspects of science they want to believe in. But science is not an a la carte menu. It’s a method of investigating evidence, not a set of beliefs. Unfortunately, many people in the anti-GMO movement believe they can select certain facts and reject others to fit their beliefs instead of embracing what the empirical evidence shows. Their suspicion at the bedrock of science—verifiable and testable hypothesis, places them at odds with one of the most thoughtful defenders of science, Carl Sagan:

The truth may be puzzling. It may take some work to grapple with. It may be counterintuitive. It may contradict deeply held prejudices. It may not be consonant with what we desperately want to be true. But our preferences do not determine what’s true.

A version of this article previously ran on the GLP on September 7, 2017.

Steven E. Cerier is an international economist and a frequent contributor to the Genetic Literacy Project