In recent years, however, regulators’ enforcement priorities have become distorted. In 2017, they sent a formal Warning Letter to a Massachusetts bakery for including “love” in its ingredient list. “‘Love’ is not a common or usual name of an ingredient, and is considered to be intervening material because it is not part of the common or usual name of the ingredient,” it said.

But while the FDA has found time to police inconsequential violations at small bakeries, the agency has been giving a pass for decades to the $47-billion-a-year organic industry’s and others’ blatantly false and deceptive advertising claims. That may be about to end.

Consider the Whole Foods website, which explicitly claims that organic foods are grown “without toxic or persistent pesticides.” In fact, organic farmers rely on both synthetic and natural pesticides to grow their crops, just as conventional farmers do, and organic products can contain residues of numerous synthetic as well as natural chemicals. USDA’s extensive, ever-changing list of allowed “organic” substances can be found here.

In addition to blatant untruths, such as that organic food production doesn’t involve the use of synthetic chemicals, food marketers are masters at subtly misleading consumers. A favored technique is the “absence claim”—asserting a meaningless distinction between products in order to make theirs seem superior. The feds would never allow an orange-juice producer to label its product “fat free,” for example, as it would imply the product is healthier than other orange juice, when in fact no orange juice contains fat.

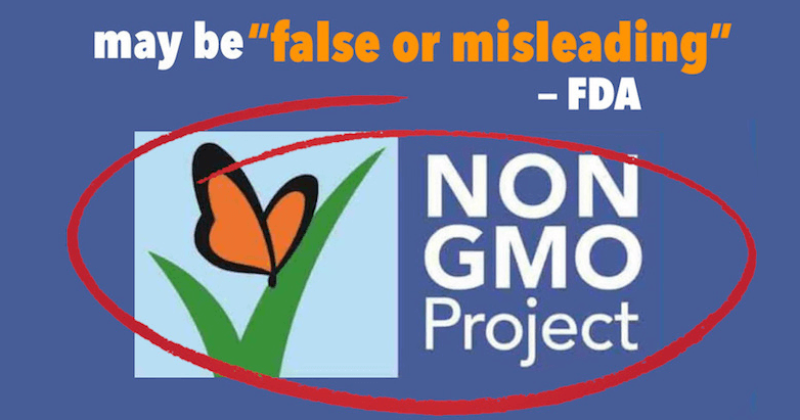

Generally, the FDA comes down hard on such behavior, but Tropicana gets away with labeling its orange juice “Non-GMO Project Verified,” and Hunt’s labels its canned crushed tomatoes “non-GMO,” even though there are no GMO (genetically modified organism) oranges or tomatoes on the market. In fact, absence claims about GMOs are never enforced: I was unable to find a single FDA warning letter or other enforcement action against deceptive “non-GMO” labeling.

The “Non-GMO Project” butterfly label emblazons more than 55,000 organic and nonorganic products on supermarket shelves today—many of which have no GMO counterpart or couldn’t possibly contain GMOs. The clear purpose of these labels, as one peer-reviewed academic study found, is to “stigmatize food produced with conventional processes even when there is no scientific evidence that they cause harm, or even that it is compositionally any different.” The labels and anti-genetic-engineering propaganda are effective: Another study found nearly half of consumers avoid GMO-labeled foods.

The FDA’s years-long inaction is all the more surprising inasmuch as they published explicit guidance on this issue in 2015:

Another example of a statement in food labeling that may be false or misleading could be the statement ‘None of the ingredients in this food is genetically engineered’ on a food where some of the ingredients are incapable of being produced through genetic engineering (e.g., salt).

That FDA guidance went even further, explaining that GMO absence claims can also be “false and misleading” if they imply that a certain food “is safer, more nutritious, or otherwise has different attributes than other comparable foods because the food was not genetically engineered.” But this (in addition to violating the “standard of presence” criterion) is exactly what Non-GMO Project’s butterfly labels are all about. Its website, considered by FDA to be a part of its labeling, describes certain foods as being at “high risk” of “GMO contamination.”

The FDA seems finally to be emerging from its organic-food-coma. Guidance issued in March indicates that the agency recognizes the widespread deceptive practices. Several critical points therein:

- “both the presence and the absence of information are relevant to whether labeling is misleading,” and “’labeling’ may extend to ‘information beyond that included on containers or wrappers, including “information that is disseminated over the internet by, or on behalf of, a regulated company.”

- The FDA discourages the use of terms on labels such as “GMO free,” “GE free,” “does not contain GMOs,” “non-GMO,” because “the term ‘free’ conveys zero or total absence,” which is impossible to verify scientifically. Moreover, the term “GMO” is ambiguous and is nowhere defined in regulations or guidance documents.

- An “example of a statement in food labeling that may be false or misleading could be the statement ‘None of the ingredients in this food is genetically engineered’ on a food where some of the ingredients are incapable of being produced through genetic engineering (e.g., salt). It may be necessary to carefully qualify the statement where modern biotechnology is not used to produce a particular ingredient or type of food.” This is typical of many of the “Non-GMO Verified” certifications.

- “Further, a statement may be false or misleading if, when considered in the context of the entire label or labeling (as noted in Section IIIA. above), it suggests or implies that a food product or ingredient is safer, more nutritious, or otherwise has different attributes than other comparable foods because the food was not genetically engineered.” Very few genetically engineered food products have “different attributes” that are discernable at the consumer level.

After I published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal last August zinging FDA director Scott Gottlieb for his inaction on this issue, he quickly tweeted out a promise under the heading “Organic” that in the “coming weeks” he was going to “put out more detailed information on what different terms mean,” and restated FDA’s responsibility in “providing consumers access to factual information in a products label…”

This updated guidance, arriving as Dr. Gottlieb departed, appears to be his parting effort to make good on that promise.

It’s a good start. It spells out, with zero room for evasion or qualification, the complete illegitimacy and legal precariousness of the Non-GMO Project. And it puts major food companies such as General Mills and Kellogg on notice that if they continue to stamp the Non-GMO Project’s butterfly on their products, they will be in clear and continuing violation of FDA rules against false or misleading advertising.

As much as the mega-food companies talk about ethics and garnering consumers’ respect for their brands, however, the question is how much they will care, unless and until FDA decides to actually enforce the law. And there’s the rub. Will the FDA follow this guidance up with long-overdue enforcement action, or will they balk once again before taking on the politically-favored organic industry?

One hopeful development is that the newly appointed acting director of FDA, Ned Sharpless, is a physician, researcher and entrepreneur who has founded two biotech firms developing cancer drugs and diagnostics and made signal contributions to cancer biology. We hope he will decide it’s time to put a stop to the decades-long propaganda war against biotechnology and, finally, make FDA enforce the law.

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is a Senior Fellow at the Pacific Research Institute. He was the founding director of the FDA’s Office of Biotechnology. Follow him on Twitter @henryimiller

This article originally ran at RealClearPolicy as FDA Moves to Level the Food-Labeling Playing Field and has been republished here with permission.