Given these staggering numbers, it would be ridiculous to claim that Western billionaires have been attempting to starve Africa’s population into decline for decades by taking control of its food supply. Nonetheless, this conspiracy theory began to gain traction with activists on the fringes of society in the mid-2000s. According to several popular accounts, the Gates and Rockefeller Foundations are “depopulating” Africa by duping farmers into growing GMO seeds patented by biotech companies like Monsanto (now owned by Bayer) and Syngenta.

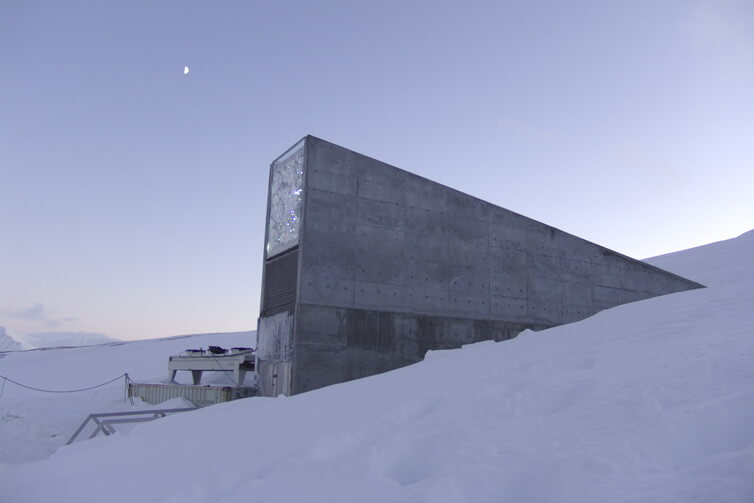

How do they know this? In 2010, the Gates Foundation was a major investor in Monsanto. Alongside Bayer and Syngenta, both philanthropies also financed the establishment of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault project in Norway, meant to preserve the world’s plant biodiversity. Through these projects, Gates, Rockefeller and “big agribusiness” are laying the groundwork for a eugenic plot to build “a master race.”

Like most conspiracies, this outlandish story starts with innocuous facts but quickly goes off the rails as its claims grow more grandiose. What’s more, different iterations of this tall tale are still embraced by many prominent anti-GMO groups today and continue to hinder Africa’s development, helping to preserve hunger and poverty on the continent.

Fact checking the conspiracy theorists

The most outlandish version of events, advanced by freelance writer and conspiracy theorist F. William Engdahl, starts with Michael R Taylor, a former Monsanto lawyer and the Obama Administration’s Deputy Commissioner for foods and veterinary medicine at the FDA, whose research was funded in part by the Rockefeller Foundation. Taylor was tasked with managing a $20 billion, three-year project to address hunger in Africa, funded by the US and other G-8 nations. During this period, Taylor was allegedly advancing this depopulation scheme under the guise of doing humanitarian work.

The problems with this story are myriad. First and foremost, if this food aid program was to see any success, it had to be led by a knowledgeable and qualified administrator. Based on his experience at the FDA and USDA, Michael Taylor fit the bill. His experience at Monsanto in no way disqualified him from running a global initiative to combat hunger. The two roles were not mutually exclusive.

There’s also some inconvenient facts that don’t fit into the depopulation conspiracy. For example, polio, that infectious disease that paralyzed and killed thousands of Americans in the 20th century, continued to afflict Africa until 2016. This was an actual depopulation crisis, and the Gates Foundation aided the eradication effort by paying off the $76 million loan Nigeria took out to finance its polio vaccination program.

Moreover, the arctic seed bank is a global effort aimed at protecting crops of diverse origin and composition for use in emergency situations, such as when it released seeds to the Lebanon-based International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas (ICARDA) in 2015. ICARDA supplies seed banks around the Middle East and was forced to withdraw samples from Svalbard as the Syrian Civil war halted its seed-growing operation and forced the organization to move from Aleppo to Beirut. It should go without saying that distributing seed to war-torn nations doesn’t help depopulate the developing world.

Why did Gates invest in Monsanto?

Biotechnology companies have been accused of selling seed to poor farmers in Africa and Asia at inflated prices, though this is because they have to recoup the cost of developing their products. It can cost over $100 million to bring a new seed variety to market. But when well-funded foundations like Gates and Rockefeller invest in seed companies, they can ensure that genetically enhanced seeds are distributed on a pro-bono basis or sold at artificially low prices to Africa’s farmers, many of whom are unable to afford them otherwise.

There’s an analogue to this investment strategy in the pharmaceutical industry. The latest anti-malaria drug was sponsored by the Gates Foundation and the price was set low enough so Africans afflicted with the disease – another depopulation phenomenon – could afford it. If wealthy foundations can invest in drug companies to make life-saving pharmaceuticals affordable, then it makes sense that they would finance research to cut the cost of improved seeds for the poorest people in the world.

GMOs developed by Africans, for Africans

Contrary to the notion that Western companies and scientists are behind the spread of GMO and gene-edited crop research programs on the continent, it is actually Africans that are spearheading these efforts. The Nigeria-based International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and National Biosafety Management Agency (NBMA) as well as the parliaments of Ugandan and Ghana helpfully illustrate this point with their support of crop biotechnology. The assumption that Africans cannot or do not conduct research into biotech crops is simply false. It also props up the mendacious notion that these countries can’t take care of their own affairs.

Science not conspiracies

Anti-biotech activists and NGOs say they support the continent’s growth. Unfortunately, many continue to endorse key components of the depopulation conspiracy, raising doubts about the sincerity of their desire to aid Africa. The Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa, for instance, claims that introducing GMO seeds to Africa is an example of “neocolonialism,” perpetrated by white Europeans “channeling the message of the biotech industry.” Other activist groups have even dishonestly told Africans that GMO seeds and pesticides cause male sterility.

The truth is that African farmers need biotech crops to feed themselves and their neighbors, as climate change makes farming an increasingly difficult profession. Consumers desire GMO-derived products for their superior quality and greater nutritional content. The continent’s population is skyrocketing and incomes are rising, which fuels demand for a greater variety of foods. It is science, not conspiracy theories, that will allow Africa to meet these challenges.

Uchechi Moses is an aspiring plant scientist based in Akwa Ibom State in Nigeria. He holds a BSc in genetics and biotechnology and writes about how capitalism and science can provide food security and prosperity for the next generation of Africans. Follow him on Twitter: @Uchechi59

This article originally appeared on the GLP on January 7, 2020.