The need for change, from farm to fork, is great.

As the twenty-first century marched forward, the fourth industrial revolution unveiled numerous game-changing technologies altering how we eat. While not everyone is familiar with Veganuary, most are acquainted with the plant-based burgers that exploded onto the food scene in the late 2010s. Countless questions followed: Is it healthier? More sustainable? Will consumers eat it? Why is food technology necessary? And is it even “real food”?

Sizzling commentary and beefy opinions abound, but nutrition, agriculture, and consumer science shows that plant-based meats—and burgers in particular—are safe and healthy options. They also carry a much smaller land, water, air, and carbon footprint than animal-based meat. Moreover, today’s savvy eaters are less concerned about the use of food processing and genetic engineering and welcome food choices that are nutritious and sustainable.

A brave new burger and the future of food

Veggie burger variants are nothing new. But better understanding of food science and technology has revolutionized the industry, finally creating a burger that looks and tastes like, well, a burger. Two companies lead the market.

Beyond Meat (est. 2009) bases its patty on pea and bean proteins and canola and coconut oils, with beet juice for color. It can be found in 17,000+ restaurants, universities, and hotels, and also offers plant-based sausage, crumbles, and chicken. Beyond Burger has a similar macronutrient profile to beef, containing 270 calories with 20 g protein, 20 g fat (5 g saturated), 5 g carb, 3 g fiber, and 0 g added sugar. Beyond Meat is having trouble keeping up with consumer demand, 70% of it coming from omnivores, and went public in 2019 to expand their manufacturing and consumer base globally.

The other big game in town is Impossible Foods (est. 2011), its burger created from soy and potato protein, coconut oil, and plant heme. While heme—which gives beef burgers their umami punch—was originally obtained from traditionally grown soy plants (i.e., on soil-based farms using land-based agriculture), it’s now made using fermented yeast that includes a gene for the heme-containing soy leghemoglobin. (Its GMO ingredient gets little attention from eaters, happily; I predict, as I have in the past, that consumers will care not at all about the use of genetic engineering and other technologies once the health and environmental benefits are clear—and tasty.)

The Impossible Burger has 240 calories and includes 19 g protein, 14 g fat (8 g saturated), 9 g carb, 3 g fiber, and <1 g added sugar. It’s offered in 5,000+ restaurants worldwide, most of them in the United States and others in Hong Kong and Macau. It arrived on supermarket shelves in 2019, and Impossible Foods launched its plant-based pork and sausage in January 2020. Fast food has gotten in on the the plant-based burger action, with Carl’s Jr, Del Taco, TGI Friday’s, and Legoland going Beyond, for instance, and White Castle offering Impossible. Burger King followed in 2019 with its Impossible Whopper. Dunkin’ Donuts launched its Beyond Sausage egg and cheese sandwich the same year—and it’s got 29% less total fat, 33% less saturated fat. 33% less sodium, and fewer calories and cholesterol than the same meat-based sandwich.

And it’s a great thing for twenty-first century consumers that value convenience: 49% of eaters globally dine at restaurants at least once weekly, 9% do so daily, and most choose fast food establishments. Happily, omnivores in high-income countries with the privilege to create a diet of their choosing are beginning to embrace vegan and vegetarian options that align with health and sustainability values, if not animal welfare. Indeed, a 2015 Nielsen survey of 30,000 people in 60+ countries found that 72% of Gen Z (aged 15-20) are willing to pay more for a sustainable product, up from 55% in 2014, alongside 73% of millennials.

By the late 2010s, the plant-based meat industry achieved five times faster growth than animal meat and accounted for around 2% of packaged meat sales. It reached $946.6 million in 2019, 10.2% more than the previous year, and is expected to hit $1B in 2020. Major food companies like Tyson, Smithfield, Perdue, Hormel and Nestlé have since jumped into the ring with their own plant-based burgers and other alternative-protein foods to appeal to eaters’ growing appetite for greener choices. They’re looking past pea protein to such foods as oats, lupin, canola, and garbanzo beans to create their own plant-based variations.

That’s a great development for the environment: alt-meat burgers may come at a fraction of the feed, water, fuel, and land cost of producing beef—and without the enormous environmental impact of deforestation, water use, greenhouse gas emissions, water and air pollution. Research funded by Beyond Meat and conducted by independent scientists at the University of Michigan found that its burger used 99% less water, 93% less land, 90% fewer greenhouse gas emissions, and 46% less energy compared to a beef burger. Similar results were found in a study of the Impossible Burger. While no peer-reviewed studies have yet been performed, a significant body of evidence—like this 2019 report of nearly 40,000 farms in 119 countries and covering 40 food products that represent 90% of all that is eaten—find higher environmental impact of meat on land, water, and air compared to plant production. While grass-fed beef can be more sustainable, it’s complicated—and hardly the panacea supporters claim it to be.

Plant-based meat that obviates animal farming also reduces greatly the risk of antibiotic resistance, among the biggest threats to public health. The CDC reported more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occurred in the US alone in 2019, and more than 35,000 people died. Meat consumption plays a critical role in this public health epidemic due to the overuse of medicines in livestock farming, which then brings antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria into our food supply.

The WHO called for the industry to stop misusing medicine in 2017, and warned in 2018 that preventing disease in healthy animals with antibiotics contributes to the resistance problem. Europe passed legislation severely restricting antibiotic use in animal agriculture in 2018. In the US, the FDA prohibits the use of medically important drugs as growth enhancers for animals, though they are still allowed in the prevention and treatment of disease. And note that misleading food labels like “antibiotic free” are meaningless: animals may not have drugs in their system at time of slaughter by law, but the risk comes from the antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

At the same time, the US remains the largest producer of grain-fed beef in the world, and USDA projects that beef and pork consumption will increase in the coming decade by 11.7% and 10.3%, respectively, a result of lower feed costs and growing demand in the US and abroad. US consumption of beef, pork, and poultry together are expected to rise to 222 pounds per person in coming years, up from 218 pounds in 2017. Dairy production will also increase, which is especially interesting given the massive surplus of milk in the US, due in part to the 2017 trade wars and decreased consumption of both milk and processed cheese. Global demand for meat and dairy is expected to increase by 70% by 2050, especially in China and India among its billions of inhabitants.

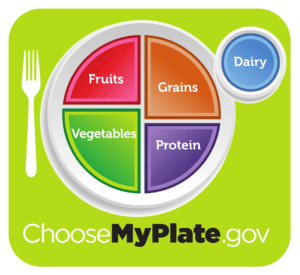

While animal protein remains essential to around one billion of the world’s indigent in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, the scientific consensus is clear that meat production and consumption habits must shift significantly to help curb climate change and mitigate other global environmental challenges. Plant-based diets are optimal for human health, too, according to diet guidelines produced by the US, Canada, and Brazil; both North American guidelines emphasize creating a plate 75% full of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains and increasing consumption of plant proteins such as beans, legumes, and soy, for instance. While not all eaters have food choices, those living in wealthier nations are afforded dining options that positively impact their own bodies and our shared planet; the evidence is robust from both scientific and consumer research that plant-based meat is a valuable alternative to animal-based fare.

Lawsuits, processed food, and junk science

Plant-based meat purchases grew 24% in 2018, and non-dairy milk, cheese, and cream also showed double-digit growth in the past two years. Industry pushback on these skyrocketing markets and their technologies ensued; so did junk science pomposity and nutrition naysaying.

In the late 2010s, beef companies filed lawsuits in Missouri, Arkansas, and Mississippi attempting to ban the use of certain words—like “meat” and “burger” and “hot dog”—from plant-based food packaging, a number of which were blocked. Vegan giant Tofurky subsequently counter-sued, along with litigants including the American Civil Liberties Union, contending such legislation violates the first and fourteenth amendment. Legal skirmishes will doubtless multiply once cellular agriculture reaches the market.

At the same time, some folks in both nutrition and activist circles began disparaging plant-based burgers as just another ultra-processed food that consumers don’t need. Beyond and Impossible certainly are processed foods, a feat of food technology requiring savvy chemistry and ingredients to mimic the mouthfeel of meat. Bravo!

What is lost from the conversation, however, is that ground meat doesn’t grow on trees—and is available only due to its own set of food processing methods and ingredients consumers simply fail to consider. For example, a wide range of additives and preservatives are needed to get that cow ground up onto your bun—in the same way additives and preservatives are needed to get plants to taste like that same meat. Such chemicals are deemed safe for human consumption; they simply keep food safe and shelf-stable. Even so, other meat production methods are more troubling (like antibiotic use and animal welfare concerns) and avoided altogether with plant-based meat. Thus, as Good Food Institute Caroline Bushnell explains, “Instead of cycling plants through animals to transform them into meat, why not make meat directly from plants?”

While the four-category NOVA classification—unprocessed and minimally processed foods, processed culinary ingredients, processed, ultra-processed—is a helpful guide, there is considerable variation in nutritional quality across groups. Indeed, numerous studies—including a report from a task force at the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and International Food Information Council—show that (ultra-) processed foods like bread and canned goods add valuable nutrients to diets; it’s the whole diet that matters.

A similar argument relates to whether alternative proteins made from plants (or via cell-based agriculture) constitutes “[real] food.” The concept was popularized by journalist Michael Pollan, whose other pithy yet parochial advice includes “eat plants, not food made in plants” and “don’t eat anything your grandma wouldn’t eat.” Food writer Mark Bittman preached, “If we’re going to embrace plant-based meat alternatives, we have to determine whether they’re actually ‘food,’ likening plant burgers to Cheetos. (Which, by the way, is also food.) Food bloggers, chefs, and countless others have jumped on this bogus bandwagon, creating nutrition confusion by employing junk-science phrases like “real food” that ultimately distract from farm more important issues in nutrition and health (like say, obesity). Here, by ultimately relying on soapbox sophistry and circular logic to claim meat from animals is inherently superior simply because it’s from an animal.

Conversely, some health professionals return to the evidence-based yet dog-tired diet advice that consumers need to eat more vegetables and fruits. A colleague of mine recently stated that people should choose peas over burgers based on isolated pea protein—which is fine advice, unless you fancy a burger. Others chide that you can make your own tasty veggie burger in your own kitchen—which you can, if you feel like cooking. Then an ivory-tower academic referred to plant-based burgers as “transitional” foods, ignoring the vibrant role burgers play in American traditions, and the science showing they can certainly be part of a nutritious diet, in moderation.

Viewpoints such as these reflect a serious lack of understanding of the drivers of food choices and the science of behavior change; they also ignore the vital role cuisine plays in cultural traditions. These commentators are, quite simply, out of touch with the way today’s consumers eat and live and the power of technology to meet food needs healthfully and sustainably—sans judgment or condescension from food experts and pundits.

Food technology solutions help meet health and sustainability goals

The science is sound: the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, World Health Organization, and other reports emphasize the critical role of plant-based diets in creating a healthy, sustainable food future for all. Solutions are therefore sorely needed to feed the growing appetite for meat in the US and abroad.

There will always be haters when it comes to food tech—and facts won’t change the minds of zealots, luddites, or elitists. But make no mistake: waxing philosophic about “real food” is immersed in white privilege among those with money and space to have such conversations; and doling out diet advice without compassion for the food issues most folks face is equally dreadful. Nevertheless, based on the individual, environmental, and public health benefits, there is little doubt that those swapping animal-based burgers for a plant-based version are doing good for their bodies, and our planet.

Yet simply telling people to eat less animal foods and consume more plant foods will not work for most; education is not enough, a truism of public health. Paramount is that taste, cost, and convenience play dominant roles in shaping food choices, while factors like health and sustainability are meaningful to only some—and even then only some of the time. And while dietary change is possible, it doesn’t happen overnight. It’s hard work that many don’t want to undertake, and the ubiquitous food environment overflowing with sumptuous and inexpensive choices undermine our every effort.

Addressing today’s complex challenges thus requires diverse tools that curb climate change, address unsustainable practices in food and agriculture, and are adaptable to varied food cultures and traditions around the world. Scientific innovations like plant-based meat will always play a role in shaping human diets, as they always have. And often for the better.

P.K. Newby, ScD, MPH, MS (“The Nutrition Doctor”) is a scientist, gastronome, and author with twenty-five years experience researching diet-related diseases. Visit her website