It was a parade like none Philadelphia had ever seen…. When the Fourth Liberty Loan Drive parade stepped off on September 28, 1918, some 200,000 people jammed Broad Street, cheering wildly as the line of marchers stretched for two miles. Floats showcased the latest addition to America’s arsenal – floating biplanes built in Philadelphia’s Navy Yard. Brassy tunes filled the air along a route where spectators were crushed together like sardines in a can.

…

Lurking among the multitudes was an invisible peril known as influenza—and it loves crowds. Philadelphians were exposed en masse to a lethal contagion widely called “Spanish Flu,” a misnomer created earlier in 1918 when the first published reports of a mysterious epidemic emerged from a wire service in Madrid.

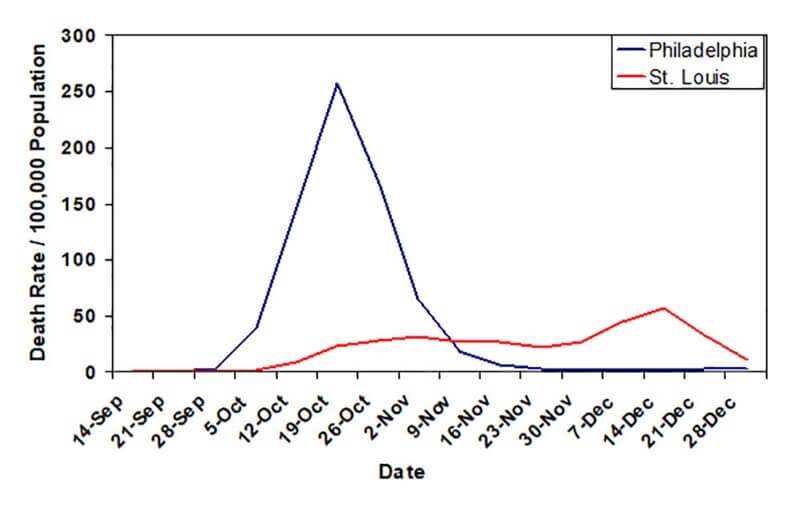

For Philadelphia, the fallout was swift and deadly.

[Editor’s note. Excerpts are from a 2018 story examining the explosion of Spanish Flu cases in 1918 caused by a failure to restrict public gatherings.]

…

Within 72 hours of the parade, every bed in Philadelphia’s 31 hospitals was filled. … A week later, the number [of people who had died from the flu] rose to more than 4,500. With many of the city’s health professionals pressed into military service, Philadelphia was unprepared for this deluge of death.

Attempting to slow the carnage, city leaders essentially closed down Philadelphia. On October 3, officials shuttered most public spaces – including schools, churches, theaters and pool halls. But the calamity was relentless.

…

Even once the war ended, famously on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the flu’s devastation did not let up. In spontaneous celebrations marking the armistice, ecstatic Americans jammed city streets to celebrate the end of the “Great War,” Philadelphians again flocked to Broad Street, even though health officials knew that close contact in crowds might set off a new round of influenza cases. And it did.

…

The pandemic touched every inhabited continent and remote island on the globe, ultimately killing an estimated 100 million people worldwide and 675,000 Americans –far exceeding the war’s ghastly losses. Few American cities or towns were untouched. But Philadelphia had been one of the hottest of the hot zones.

…

[This is] a good moment to remember the damaging costs of shortsighted medical decisions shaped by politics during a pandemic that was more deadly than war.