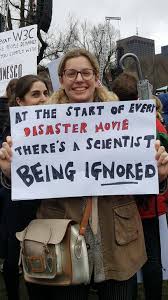

An internet meme is circulating worldwide in the heat of the COVID-19 pandemic: “Every disaster starts with a scientist being ignored.” Movies like “Outbreak” and “Contagion,” featuring both scientists whose advice was disregarded and an animal virus that jumped into humans, are topping the charts at Netflix and Amazon Prime Video.

There’s a very strong risk, especially in Europe and the United States, that the wisdom and guidance of numerous scientists who are about to be ignored or ostracized. But they’re not the likes of Chris Whitty or Anthony Fauci. Rather, they are specialists in gene editing and agricultural biotechnology who are being targeted as enablers of the coronavirus pandemic.

Trying to capitalize on confusion about the origins of the disease, many longtime critics of GMOs and advocates of organic farming and all its recent iterations—regenerative, biodynamic and agro-ecological—are in effect blaming conventional farming, which they derisively call ‘industrial agriculture,’ as the proximate cause for the crisis. Some of the claims are beyond outrageous.

- From University of California-Berkeley agronomist (and organic promoter) Miguel Altieri: “Because of their low ecological diversity and genetic homogeneity, [large scale farms] are highly vulnerable to weed infestations, insect invasions and disease epidemics, and recently to climate change.”

- From the Sierra Club: “The reason COVID-19 was able to leap into the human population has less to do with wild bats and the viruses they carry and more to do with the way that certain Western-influenced farming practices affect the health of humans and wildlife and virtually guarantee the periodic emergence of diseases.”

- From Ronnie Cummins, head of the Organic Consumers Association (OCA): “We will have to eliminate factory farms (the perfect breeding grounds for disease and pandemics) and industrial food production.”

There are elements of truth in many of these claims. Viruses can jump from wild animals into humans, with increased enroachment on natural habitats and changes in climate playing a role. The part that isn’t grounded in anything more speculation, however, is the link to so-called “industrial agriculture,” a vague, politicized term (omg, ‘industry’ is perpetrating evil) designed to close discussion before it even begins. They sprinkle this ideological manipulation of the debate with claims that “zoonotic disease” like COVID-19 come about specifically because of conventional, “industrialized” agricultural practices. Surprise, surprise, only veganism, organic or biodynamic farming can prevent these animal-to-human jumps from happening. Conclusion: Big Ag is to blame for setting the stage for global catastrophe.

OCA’s Cummins elaborates on this thesis:

To avoid future pandemics, to stop the spread of antibiotic resistance and the food- and environment-related chronic diseases that are now reaching epidemic levels (cancer, heart disease, obesity, diabetes, pulmonary deterioration), and that constitute a major co-factor in COVID-19 deaths, we will have to eliminate factory farms (the perfect breeding grounds for disease and pandemics) and industrial food production, transform the diets and eating habits of the population and drastically reduce air pollution.

This means moving from chemical- and energy-intensive industrial agriculture, transportation, utilities and manufacturing to re-localized green and regenerative practices. It means putting an end to the deforestation, habitat destruction, economic exploitation, globalized trade wars and geopolitical belligerence that threaten us all.

Blaming the jumping of viruses from animals to humans on conventional farming practices strains credulity and science. The mechanisms by which animal viruses “jump” to humans is not well known but they have happened over millenia. Such “spillover” events are tenuously linked to agricultural practices, however. Researchers still don’t understand exactly how viruses make the geographic and physiological leap, and what environment encourages that leap. Any human-induced changes in the environment can play a role in triggering the introduction of a new virus:

- HIV was introduced into humans by consumption of bushmeat; chimpanzees and bonobos killed and consumed by workers on various construction projects and other forays into their habitat. Ebola also jumps into people thanks to hunting monkeys and consuming bushmeat.

- Influenza often originates in birds, which can fly great distances and infect humans over a wide geographic range.

- Humans can also transmit infections to animals. Ecotourism was determined the cause of transfer of the measles virus from people to apes, for example.

- Large “wet markets,” in which live and dead, domestic and wild, animals are sold for food or traditional medicine, have been blamed for a number of viruses, including coronavirus cases. These markets are not by any measure examples of “industrial agriculture”; rather they create an interface between illegally (and legally) obtained wild animals that are transported in and sold.

- Bats are a common “vector” for transmission. Like birds, they fly over large distances. and are quite comfortable in urban settings, so human human expansion into natural areas is not necessary.

- An immune system that resists viruses that are pathogenic to us also helps.

Encroachments into wilderness can come from land clearing for a number of purposes, including urbanization, “suburbanization” (people wanting to live near a natural setting), road and railroad building, as well as for livestock and crop raising. And these occur in socialist and totalitarian political structures just as much as in capitalist ones. The role of agricultural systems is far down the list of causal factors driving pandemics.

We need more industrial agriculture, not less

So what do we make of these arguments ‘fingering’ large-scale agriculture (note that an increasing amount of organic products are now grown on ‘industrial’ farms)?

Looking at the evidence stripped of ideological loading, farming practices that reduce land footprint are more sustainable. Efficiently planned roads and smaller plots of crop or land for livestock would all reduce the interface between wild and human. Using that standard, organic farming poses major ecological challenges. Yield lag is huge, from 10%-35%. A report by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis noted that intensification, particularly cutting edge methods including biotechnology, could reduce farmland usage area by nearly half in decades to come. These methods include targeting crops to appropriate farmlands and more nutrient inputs.

As the Breakthrough Institute has noted, higher productivity, driven by technology adoption, remains the primary environmental benefit of farm consolidation. In the US, yields are higher and have grown faster on large farms. And it is thanks to such yield growth that the worldwide agricultural land use per person is roughly half what it was in 1960, which has massively reduced carbon emissions and habitat loss compared to a flat-yield scenario. More land to arrive at the same output would put more land and animals at risk, not less. Using technological advances, including gene-editing techniques like CRISPR, to improve crop traits (like the ability to thrive in droughts and other adverse conditions) and increase yields would help us minimize the consequences of experiencing future pandemics; they are clearly not the proximate cause of them.

Andrew Porterfield is a Contributing Correspondent to the Genetic Literacy Project. He is a writer and editor, and has worked with numerous academic institutions, companies and non-profits in the life sciences. BIO. Follow him on Twitter @AMPorterfield