Anti-GMO folk hero and canola farmer Percy Schmeiser was the best-known avatar of the idea that Monsanto, now part of Bayer, went on a lawsuit spree against small farmers for patent infringement in the mid 1990s, allegedly because their farms were accidentally contaminated by the biotech giant’s GM seeds.

In part one of this series, we demonstrated that Schmeiser, recently deceased and the subject of a feature film starring Christopher Walken, was not sued for accidental contamination of his fields, but rather for saving herbicide-tolerant (Roundup Ready) canola seed he found on his property and planting 1,000 commercially viable acres of the crop. Canada’s Supreme Court ruled in favor of Monsanto, finding that Schmeiser benefited from a technology he didn’t pay for. Contra the popular underdog story, David wronged Goliath, as far as the Court was concerned.

[Editor’s note: This is part two of a three-part series. Read part one and three.]

But if the popular version of Schmeiser’s story is wrong, what about the other narratives that prop up this popular David vs. Goliath meme?

Between 1997 and 2010, Monsanto filed 144 patent infringement lawsuits against farmers, and settled 700 more cases out of court, according to the Organic Seed Growers and Trade Association (OSGATA). There are three high-profile stories that I’m aware of that planted the seeds (ahem) of this persistent narrative: suits against Moe Parr, a seed cleaner; Vernon Bowman, a soybean farmer; and Pilot Grove Co-op. There is a final lawsuit, brought by OSGATA, that we’ll examine in part three of this series. Properly considered, these cases should disabuse everyone of the notion that Big Ag wrongly targeted farmers in court.

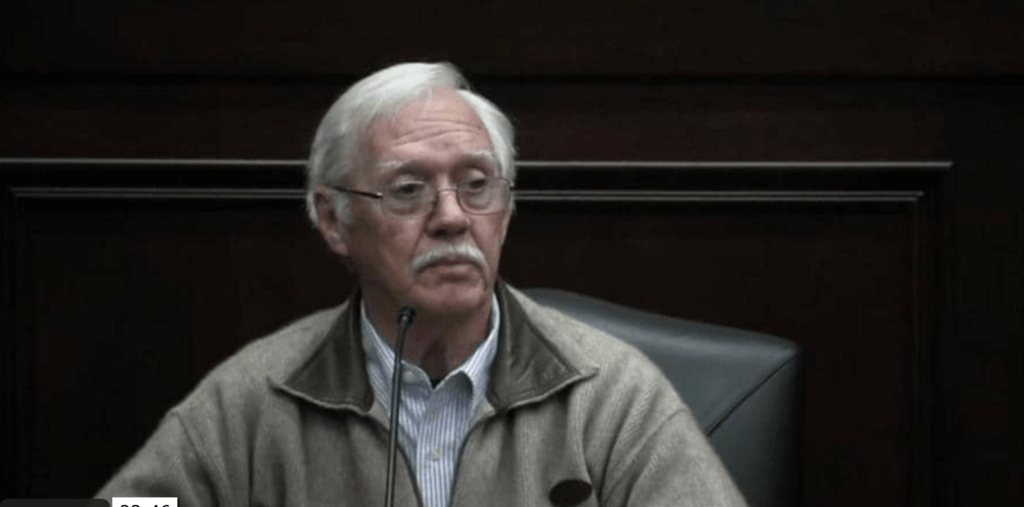

Moe Parr

In 2008, Monsanto sued Maurice Parr, a seed cleaner, for “aiding and abetting farmers” illegally saving their seeds. “Mr. Parr made clear to his clients that he was not responsible for enforcing seed patent agreements to which he was not a party,” according to a report by the anti-biotech Center for Food Safety (CFS). “Monsanto sued him …. claiming his statements encouraged flouting of their patents.” This narrative was amplified by other anti-biotech voices, including GM Watch and Greenpeace:

According to Parr, the lawsuit cost him over $25,000 in legal fees and 90 percent of his former customers, who feared that doing business with him could lead to their being sued. But it is clear from the injunction issued against Parr that he did not clearly inform his clients that he was not responsible for enforcing seed patent agreements; in fact, he misled them about the permissibly of saving patented seed covered by technology agreements. He made this decision after Monsanto gave him the opportunity to mend his ways.

In 2002, Monsanto sent a letter by certified mail to Parr, explaining that it was the owner of the patent covering Roundup Ready soybean seed and that a limited-use license was required to use the crop seed. Saving a crop grown from the licensed seed for planting or selling for replanting was an infringement. The letter stated that Monsanto had confirmed Parr’s seed-cleaning business facilitated seed replanting, and further that Parr encouraged growers to clean and replant soybeans which he knew contained Monsanto’s patented technology.

Finally, the notice requested that Parr cease any actions that induced patent infringement and specifically asked him to stop cleaning any seed containing Monsanto’s patented Roundup Ready biotechnology; and to stop advising growers that they were entitled to save and replant seed containing Monsanto’s patented Roundup Ready biotechnology.

Parr wrote back, expressly stating that he would give all his customers a copy of the Monsanto notice, and ask them to sign a statement confirming that they were not asking Parr to clean seed containing Roundup Ready technology. Subsequent to this exchange, a number of soybean growers used Moe Parr’s seed-cleaning services to clean and condition their Roundup Ready seed for replanting. Monsanto negotiated settlements for the infringement with eleven farmers that used Parr’s seed cleaning services.

According to the injunction, Parr advised Gary Williams, one of his seed-cleaning customers, that it was OK to save Roundup Ready soybeans and replant them on his farm. Prior to 2004, Williams had used Parr’s seed-cleaning services on non-Roundup Ready soybeans. At some point in 2003 or 2004, Williams testified that he asked Parr about cleaning Roundup Ready soybeans, and was told that it was permissible for a farmer to save Roundup Ready soybeans for his own use. After this discussion, Williams felt that it would be safe to save, clean and replant Roundup Ready soybeans. This is understandable. We expect people engaged in a business to be more familiar with the law than their customers and give dependable advice. Williams therefore saved some of his 2005 Roundup Ready soybean crop, had it cleaned, then planted that saved seed in the 2006 growing season.

Fred and Jim Inskeep testified that Parr convinced them it was permissible to save Roundup Ready soybeans and replant them on their farm. Parr told the Inskeeps that it was legal for a farmer to save, clean, and replant Roundup Ready soybeans. Parr went so far as to cite legal chapter and verse, explaining that the Supreme Court’s opinion in Asgrow Seed Co. v. Winterboer indicated that replanting patented seed was permissible, even giving the Inskeeps a copy of the opinion. That would have been a compelling argument, but Asgrow v. Winterboer was relevant to conventional seed covered under a standard patent rather than a patent and technology license. Unaware of these crucial details, the Inskeeps subsequently saved some of their 2005 Roundup Ready soybean crop, had it cleaned by Parr, and planted that saved seed in the 2006 growing season.

The court found that Moe Parr was indeed actively aiding and abetting his customers in illegal seed saving, and in some cases inducing farmers to illegally save seed, even after Monsanto had tried to reach an understanding in 2002. Mr. Parr was thus barred from cleaning or conditioning crop seed that contains the Roundup Ready trait, or making statements or distributing information suggesting that it is legal or otherwise permissible to save, clean, and replant Roundup Ready soybeans. He was required to inform his customers that it is illegal to save, clean, and replant Roundup Ready soybeans. He was required to post a notice on his seed cleaning equipment:

Do Not Ask to Clean Roundup Ready Soybeans. All Brands of Roundup Ready Soybeans Are Patented. Replanting Is Prohibited.

Parr also had to have his customers certify in writing that the soybeans they were cleaning did not contain the Roundup Ready trait, then give Monsanto the written certifications, along with a sample of the seed cleaned, within thirty days of each load of seed. The judge awarded Monsanto $40,000 in compensation for past infringement. The company agreed not collect as long as Parr honored the terms of this order.

Pilot Grove Co-op

The case of Pilot Grove Co-op became well-known when a Pulitzer Prize-winning pair of journalists, Donald L. Barlett and James B. Steele, did a story on Monsanto’s hardball tactics for Vanity Fair in 2008. They are considered among the finest investigative journalists in America in the last half-century, but in their expose on Monsanto they were a bit out of their depth in rural America, led around a bit too credulously by The Center for Food Safety, a notorious anti-GMO group whose fingerprints were all over the piece.

The reporting hopscotched through a few incidents that CFS had been trying to promote and betrayed an all-too-typical urban set of biases about whether farming should be treated like any other business, or given some pastoral insulation from the realities of the marketplace. It was sentimental about the role of technology and law in agriculture and a bit lazy in letting the David and Goliath allegory shape the narrative.

After setting the stage with the unfortunate story of Gary Rhinehart, a store owner who Monsanto pursued aggressively and unfairly because they had mistaken him for someone else, Bartlett and Steele turned to the story of Pilot Grove, which was ongoing at the time. Monsanto approached Pilot Grove Cooperative Elevator (of Pilot Grove, Missouri) in the fall of 2006. The co-op was doing around $15 million in annual sales, with seven employees and four computers, buying corn and soybeans from local farmers and selling them into the commodity markets.

According to Bartlett and Steele, Monsanto suspected the co-op was helping its customers commit patent infringement and hired a private investigation firm to take surveillance video of Pilot Grove’s customers and employees as they went about their business:

Not long after investigators showed up in Pilot Grove, Monsanto subpoenaed the co-op’s records concerning seed and herbicide purchases and seed-cleaning operations. The co-op provided more than 800 pages of documents pertaining to dozens of farmers. Monsanto sued two farmers and negotiated settlements with more than 25 others it accused of seed piracy.

But Monsanto’s legal assault had only begun. Although the co-op had provided voluminous records, Monsanto then sued it in federal court for patent infringement. Monsanto contended that by cleaning seeds—a service which it had provided for decades—the co-op was inducing farmers to violate Monsanto’s patents. In effect, Monsanto wanted the co-op to police its own customers.

The case was still pending during Bartlett and Steele’s reporting, but the outcome of the litigation was well documented. While Monsanto certainly employed hardball tactics and leveraged their power and resources relative to the co-op, it turned out that Pilot Grove had violated the law. Then Reuters reporter Carey Gilliam, now employed by anti-GMO group US Right to Know (and thus no friend of Monsanto), noted that the co-op acknowledged its patent infringement and agreed to better train its employees, fund college scholarships and adopt a policy that avoided future violations. Monsanto provided further detail: Under the terms of the settlement, Pilot Grove Cooperative deposited $275,000 in an account—and the income from that account funded scholarships for the Cooper County, Missouri, FFA and 4-H programs. Hardly a rapacious Goliath-crushes-David settlement.

Vernon Bowman

Vernon Bowman’s case is interesting because he decided the law was on his side (or should have been) and planted soybeans that he wasn’t licensed to plant—then went and told Monsanto. He ended up testing the concept of patent exhaustion as it relates to seeds in the courts and lost.

In 1999, Indiana farmer Vernon Hugh Bowman bought soybeans from a local grain elevator for his second crop of the season. He saved seeds from his second crop to replant additional crops in later years. Bowman had purchased these seeds from the same elevator to which he and neighbors sold their soybean crops, many of which were Roundup Ready. The elevator sold these soybeans as commodities, mostly for livestock feed, not as seeds for planting.

Bowman tested the new seeds and found that, as he had expected, some were transgenic (GMO) and thus were Roundup Ready. He replanted seeds from the original second harvest in subsequent years for his second seasonal planting, supplementing them with more soybeans he bought at the elevator. Bowman then informed Monsanto of his activities

Monsanto took the position that Bowman was infringing its patents, because the soybeans he bought from the elevator were products that he purchased for use as seeds without a license from Monsanto. Bowman’s position was that he had not infringed due to patent exhaustion. He felt that Monsanto’s patent was ‘exhausted’ on the first sale of seed to the grain elevator and that his purchase from the grain elevator did not carry the use restrictions that farmers who had sold the soybeans to the elevator agreed to.

In 2007, Monsanto sued Bowman for patent infringement in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana. In court, Bowman argued that if Monsanto was allowed to continue its license past exhaustion, it would be able to dominate the market. The district court found Bowman’s arguments compelling, however, it found that it was bound by previous appellate court decisions in Monsanto Co. v. Scruggs and Monsanto Co. v. McFarling. The district court ruled in favor of Monsanto. The court entered judgment for Monsanto in the amount of $84,456.30 and enjoined Bowman from making, using, selling, or offering to sell any of the seeds from Monsanto’s patent.

Bowman then appealed to the US Court of Appeals Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit upheld the lower court’s finding. On appeal to the Supreme Court, Bowman’s lawyers argued that the lower court’s ruling was inconsistent with various case law that had found that secondary resale of products did indeed exhaust the rights of the patent holder. This turned out to be a strong enough argument for the Court to choose to hear the case, but not to prevail. The Supreme Court ruled against Bowman unanimously.

In her opinion for the majority, Justice Elena Kaga, an Obama appointee, held that while an authorized sale of a patented item terminates all patent rights to that item, that exhaustion does not permit a farmer to reproduce patented seeds through planting and harvesting without the patent holder’s permission. When a farmer plants a harvested and saved seed, thereby growing a further soybean crop, that action constitutes an unauthorized “making” of the patented product. Justice Kagan concluded that Bowman could resell the patented seeds he obtained from the elevator, or use them as feed, but that he could not produce additional seeds.

Did Monsanto play hardball? Yes. Were the targets of their litigation often outmatched? Certainly. Being put under surveillance by private investigators and having a team of high-priced lawyers going over all the details of your business is no picnic. Nevertheless, two facts emerge when you dig into the details of these highest-profile cases held up by anti-GMO groups. First, in none of these cases was the issue accidental pollination. These were intentional violations of Monsanto’s patents and technology licenses. Second, the law was on Monsanto’s side in every case.

That doesn’t mean the law is necessarily just or correct — though I personally think that, on balance, it’s about right — but to argue that you don’t like the legal environment that farmers and Monsanto/Bayer operate in significantly moves the goalposts from blaming Monsanto for bullying farmers for accidental contamination.

Marc Brazeau is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on agricultural biotechnology. Follow him on Twitter @eatcookwrite