When it comes to science, how much do media narratives influence public opinion and policy?

The answer is, a lot. That can be good, for example, in encouraging vaccination against COVID-19. But in other murkier waters, entrenched narratives can actually turn people away from science and endanger both themselves and the environment.

Let’s take the case of Carey Gillam, the activist journalist, who has been a decade-long critic of technology in agriculture. For years she was a Midwest reporter for Reuters. She left in 2015 under hazy circumstances after her reports on crop biotechnology, often laced with opinions, came under criticism from colleagues and scientists.

Let’s take the case of Carey Gillam, the activist journalist, who has been a decade-long critic of technology in agriculture. For years she was a Midwest reporter for Reuters. She left in 2015 under hazy circumstances after her reports on crop biotechnology, often laced with opinions, came under criticism from colleagues and scientists.

She then joined the anti-GMO, anti-pesticide, pro-organic lobbying group U.S. Right to Know (USRTK) in prosecuting the tort case against the weedkiller Roundup, whose active ingredient is glyphosate.

Gillam is in the news because she has come out with a new book, The Monsanto Papers. Recently, the website Civil Eats published an interview with her about the book and the legal cases involving glyphosate. Civil Eats, which has no standing in the science community and is consistently anti-biotechnology and pro-organic, describes itself as a “news source devoted to critical thought about the American food system, sustainable agriculture, and efforts to build economically and socially just communities.” The website has posted more than 100 articles on glyphosate and the controversy around it but not once did it review the scientific literature on glyphosate’s effectiveness and safety, which is easily accessible — and contradicts the thrust of many of Civil Eat’s articles.

Gillam’s case against Monsanto/Bayer

In view of the prominence of Gillam’s writings on glyphosate and the Monsanto/Bayer trials — her name comes up first in a Google search on “Roundup journalism” — and the influence her writings appear to have had on the trials and on the wider discussion surrounding glyphosate, it is revealing to examine the case she makes and the evidence she cites, as well as what she leaves out.

Before proceeding, it’s helpful for context to highlight the way Gillam frames her articles and books. Rather than make her case based on science, she focuses on anecdotes specifically chosen because there is no way to scientifically verify her claims. She cites the terrible suffering of plaintiffs against Monsanto, who have been diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) as tangible proof that glyphosate has caused their disease. In this way, Gillam creates a strong emotional association between glyphosate and NHL. However, it is axiomatic that one can’t infer causality based on individual cases. But Gillam is aware that this cognitive shortcut appeals emotionally to the general public.

In articles in The Guardian and her two books (Whitewash: The Story of a Weed Killer, Cancer, and the Corruption of Science and The Monsanto Papers), Gillam repeatedly makes the following claims:

- Monsanto marketed a product which it knew is unsafe and carcinogenic

- Monsanto failed to warn users of the dangers

- The company hired scientists to ghostwrite articles defending glyphosate

- The company conducted a campaign to undermine the credibility of journalists who criticized Monsanto

First, let’s review how Gillam’s claims stand up; then the important facts she fails to acknowledge; and, finally, the role her writings have played in the controversy surrounding the safety and appropriate use of glyphosate — a controversy at the heart of one of the largest tort cases in U.S. history, but which also has implications for farming practices worldwide and the availability of affordable produce.

First, let’s review how Gillam’s claims stand up; then the important facts she fails to acknowledge; and, finally, the role her writings have played in the controversy surrounding the safety and appropriate use of glyphosate — a controversy at the heart of one of the largest tort cases in U.S. history, but which also has implications for farming practices worldwide and the availability of affordable produce.

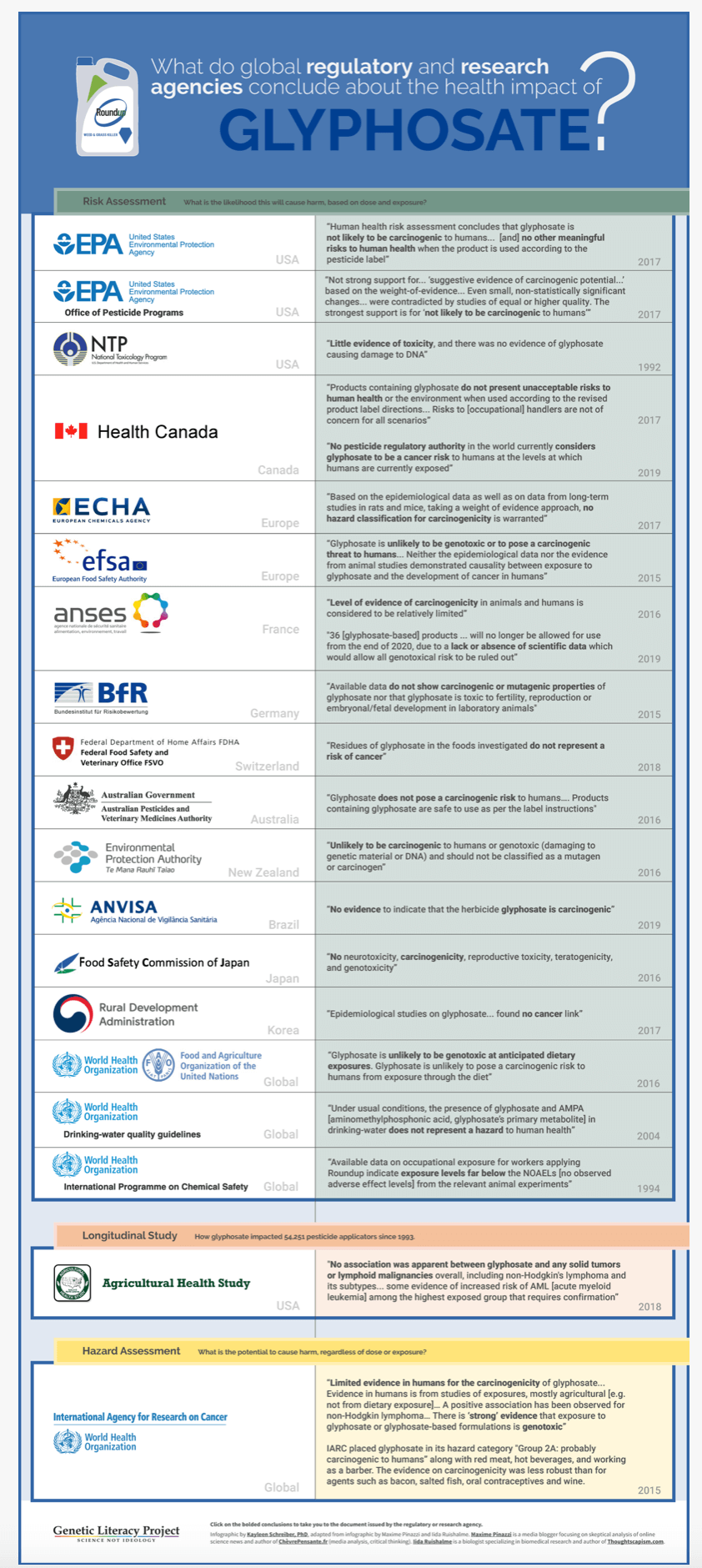

Regarding Gillam’s first point, after comprehensive and, in some cases, repeated reviews of thousands of studies, 17 national and international regulatory and scientific agencies have found glyphosate to be safe and non-carcinogenic. There is only one exception to this consensus, which we will come to shortly. [To view the graphic in full with links to the studies, click here]

The consensus among regulatory and scientific agencies undermines Gillam’s claim that Monsanto failed to warn users that glyphosate can cause cancer and is unsafe, since the evidence resoundingly speaks against this. Needless to say, glyphosate has long carried a label cautioning users to avoid contact with the skin and to use the compound the way one would use any chemical.

Gillam’s third and fourth claims charge Monsanto with engaging in various unsavory practices including sponsoring the ghostwriting of scientific articles and targeting journalists, including Gillam herself, who portrayed Monsanto in an unflattering light. While some of these practices seem reprehensible, others appear to be simply standard tactics employed by companies to defend their brand. Few organizations or companies engaged in the rough-and-tumble of the marketplace are vying for awards for ethical behavior.

When Gillam’s points are presented baldly, without any context, they appear damning. However, once one is aware of the context, they turn out to be either misleading (claims 1 and 2) or considerably less scandalous (claims 3 and 4). Her strategy appears to be to divert attention from what scientists have learned about the health effects of glyphosate from four decades of study.

What Gillam leaves out

The Civil Eats interviewer, Anna Lappé, who calls herself a “food justice” advocate, introduced Gillam as a “veteran journalist.” Lappé then tells us that Gillam “pored over 80,000 pages of exhibits and documents and a 50,000-page trial transcript to reveal a chilling story of decades of doubt, denialism, and deflection that allowed glyphosate to become the most widely used herbicide in the world.”

Throughout the interview, Gillam presents herself simply as a researcher “trying to hold the company [Monsanto/Bayer] accountable.” At no point did Lappé inquire about the many aspects of the glyphosate issue that Gillam conveniently ignores or about Gillam’s own conflicts-of-interest.

The most striking feature of the interview is that Gillam avoids adducing a single piece of scientific evidence. Her whole position rests on a single report from a single agency—the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which is loosely affiliated with the World Health Organization.

“These were independent scientists at the top of their field, brought in from around the world, with no ties to any company or any activist group, and they determined glyphosate was a probable human carcinogen, with an association of non-Hodgkin lymphoma,” she tells us.

Because the IARC report is the key document Gillam relies on to support her position, we need to take a closer look at it. As mentioned earlier, 17 other international and national regulatory agencies, including three divisions of the World Health Organization, have evaluated glyphosate exhaustively and found it to be safe and not carcinogenic.

Rather than accepting IARC’s assessment based on the agency’s self-proclaimed authority and transparency, we have to look at specific aspects of its review.

Disturbing questions about IARC’s glyphosate assessment

In recent years, the IARC Monographs program responsible for evaluating carcinogens has become increasingly politicized as the agency has adopted a precautionary approach and excluded qualified industry scientists from its deliberations. As a result, IARC has issued a number of confusing and poorly-supported assessments regarding such different risks as red meat, cell phones, coffee, glyphosate, and other agents.

As shown in deposition transcripts that are public, American scientist, Christopher Portier, who chaired the advisory group that originally proposed that glyphosate be evaluated by IARC and served as invited specialist on the working group that evaluated glyphosate, became a litigation consultant for two law firms suing Monsanto within days of the publication of the IARC glyphosate assessment in 2015.

In a series of investigative reports, Kate Kelland reporting for Reuters found multiple instances of IARC’s putting its hand on the scale in evaluating the evidence (here and here). In addition, cancer epidemiologist Robert Tarone has published two articles demonstrating that IARC selected evidence of a positive association of glyphosate with tumors in animals but ignored results suggestive an inverse association (here and here). (IARC’s case against glyphosate was based on the false claim that there was sufficient evidence of carcinogenicity in animals).

In a large prospective cohort investigation (the Agricultural Health Study) carried out by the National Cancer Institute, 54,000 pesticide applicators were followed for twenty years. Over 80 percent of the workers were exposed to glyphosate. The results showed convincingly that exposure was not associated with any type of cancer, including non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In the authors’ words, “In this large, prospective cohort study, no association was apparent between glyphosate and any solid tumors or lymphoid malignancies overall, including NHL and its subtypes.”

The results of the AHS were not published until 2018, after the IARC report. However, Aaron Blair, the scientist who chaired the IARC Working Group on glyphosate in 2015, was aware of the results. Reuters reported in 2017 that Blair withheld information showing no link between glyphosate and cancer. In sworn testimony, Blair acknowledged the data would have altered IARC’s conclusion, i.e., would have made it less likely that glyphosate would meet the criteria for being classified as “probably carcinogenic.”

IARC’s anomalous and widely-questioned determination that glyphosate is a “probable carcinogen” provided the needed justification for litigation against Monsanto, as is clear from the trial transcripts.

The tort machine

Shortly after IARC’s 2015 assessment, the first toxic tort cases were filed against Monsanto, the original producer of Roundup, and its successor company Bayer, in 2016 in the San Francisco Bay area. It is not a coincidence that the cases were brought in California, where IARC’s determinations carry great sway, and the state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) invariably follows IARC’s lead in classifying carcinogens. In July 2017 OEHHA had listed glyphosate as “known to cause cancer” under the state’s Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, also known as Proposition 65.

As explained by David Zaruk, professor of risk communication at Odisee University College in Belgium, two conditions are necessary for a law firm to mount a successful ‘toxic tort’ campaign against a large corporation. First, one needs to link an industrial product, no matter how tenuously, to cancer. Second, one needs to focus public outrage against the company and continue to maintain that outrage throughout the prolonged legal process.

IARC’s glyphosate judgment satisfied the first condition. All the plaintiff’s attorneys had to do was to cite the IARC report as revealed truth. Activist lobbyists—Gillam first and foremost— satisfied the second condition.

These cases are decided by a jury; all that is necessary is to convince a jury that the defendant (the corporation) acted negligently and that its product could have caused the plaintiffs’ illness. Rather than assessing the complicated science, which expert witnesses for the plaintiffs and the defense parse very differently, juries are influenced by the powerful emotional drama pitting a ‘reckless corporation’ against its ‘unfortunate victims’: David v. Goliath.

In the first three cases, staggering dollar amounts (ranging from $80M to $2B) were awarded to the plaintiffs, although the awards were reduced on appeal (ranging from $2.5M to $87M). Spurred by these settlements, a steady stream of new cases was brought. The intent of this strategy was to force Bayer (which acquired Monsanto in 2018) to agree to settle out of court. As of today, there are more than 100,000 cases pending. Bayer has now proposed a $11B settlement.

Gillam’s central role in the anti-biotech and anti-agricultural chemical lobby

Carey Gillam’s “journalism” has played a crucial role in keeping outrage focused on Monsanto/Bayer. It is significant that the organization she works for, USRTK [GLP profile], was founded with seed money from the Organic Consumers Association, an organic industry-funded group [GLP profile] started by the anti-technology activist Jeremy Rifkin, that promotes natural health, supplements, and homeopathy, and warns of the “dangers” of vaccines, including COVID-19 vaccines.

Gillam would have us believe that she is just “one little gal in Kansas who writes a book or two.” But, in fact, she is a master at disseminating disinformation. She has perfected the game of using the sensational drama of plaintiffs with a poorly understood disease in order to demonize what has been a spectacularly useful and effective product with low toxicity (here and here).

That’s cynical on her part. She must be aware of what the independent science concludes about crop biotechnology but realizes that discussing complex scientific studies cannot compete with her narrative of a ‘ruthless corporation sacrificing human lives for profit’.

Note: Since Gillam cannot rely on the science to support her claims, she and US Right to Know instead vilify scientists who publicly address the subject of pesticides, glyphosate, GMOs, and modern agriculture generally. Therefore, it’s important to make clear that my interest in this issue stems from my career as an epidemiologist focused on what we know about the actual causes of cancer and how to prevent cancer. I have never received funds from, or communicated with, Monsanto/Bayer or any other company that manufactures pesticides. Additionally, the editor of Significance magazine, published by the Royal Statistical Society, has investigated in depth USRTK’s claims that two organizations that I have been affiliated with work with Monsanto to discredit its critics and have taken funds from Monsanto, and found no corroborating evidence.

Geoffrey Kabat is cancer epidemiologist and the author, most recently, of Getting Risk Right: Understanding the Science of Elusive Health Risks. Find Geoffrey on Twitter @GeoKabat