It’s been ten years of downhill sledding for advocacy groups and activists campaigning to throttle the burgeoning biotechnology revolution transforming both medicine in agriculture. The success of COVID vaccines, most of which were engineered in one way or another, has opened the public’s eyes to the vast potential and demonstrable benefits of genomic tinkering.

In the food and farm sector, from cell-based meat to climate-tolerant crops, advances are rolling out around world. Less and less talk about organic farming with its 20-40% yield lag; more and more focus on true sustainable agriculture that reduces inputs, from water to chemicals; limits pests; and increases yields. We are on the way to massive shift toward sustainable farming—if anti-GMO activists do not throttle technological advances the way they partly sidelined the GMO revolution 2o years ago. With climate change disruptions already roiling the globe, openness to change is in the wind.

We are all aware of the massive knowledge shift over the past decade with the discover of CRISPR gene editing and other biotech innovations. What are the other factors that led to the reduction in the power and influence of the science rejectionist ‘natural’ wing of liberal America?

Read part two here: Seeds of Reaction — How anti-GMO ‘progressivism’ morphed the technophobic science rejectionist movement

A long time coming

The food and science landscape and the potential for future breakthroughs looked a lot different ten years ago. In 2012, the anti-GMO movement was riding high after more than a decade of spreading distrust about most things biotechnological. Its proponents were mostly old-line environmental groups and ‘natural movement’ supporters, whose opposition to GMOs was rooted in a precautionary suspicion of technology and belief that global food production was driven by corporate interests.

The activists—led by such well-known but scientifically compromised advocacy groups such as Environmental Working Group, Center for Food Safety and the Organic Consumers Association—spearheaded a high-profile labeling referendum in California that if successful would put a figurative skull and crossbones label on every product that originated from genetically modified seeds. In the US, that would be food made from eight crops at the time: soybeans, corn (field and sweet), canola, alfalfa, sugar beets, summer squash, and papaya (cotton was also genetically modified). Their goal was to sow distrust in the federal oversight of food in the country to spark an organic-led backlash.

While enormously popular in early polls in California, the the anti-GMO campaign stumbled out of the gate. After showing sizable support, the initiative surprisingly and narrowly lost in November 2012, a humiliating defeat for the activist coalition. The public came to recognize the increased costs labels would bring and the hypocrisy at the heart of the measure: the proposed law exempted numerous products that were certified organic, made from animals fed or injected with genetically engineered material (but not genetically engineered themselves), processed with or containing only small amounts of genetically engineered ingredients, or administered for treatment of medical conditions. Restaurants could use any food grown from GMO seeds, and alcoholic beverages, many of which use GMO ingredients (vodka, such as Tito’s, can be made from GMO corn).

Science and safety became part of the debate The public ultimately did not buy false claims by GMO opponents that crops grown from modified seeds were unsafe Frankenfoods, a key insinuation of anti-GMO activists. In other words, the public recognized the measure was laced with exceptions that favored the organic industry or inconvenienced people with few if any tangible benefits.

Activists regrouped over the next year, then targeted Washington state in November 2013, but suffered yet another upset defeat after being heavily favored in early polls. Hoping to resurrect their cause, they moved east and modified tactics. It would only take two states in different parts of the country, they reasoned, to upend the tightly intertwined supply chain, as grocery chains were unlikely to label products differently to accommodate local laws. If they could get an initiative in two liberal bastions in different parts of the country passed, they could create chaos in the food supply chain and force the grocery industry to move to scare labels.

Targeting Vermont and Colorado

Liberal Vermont was chosen to revivify the movement. Activists targeted an April 2014 election. Anti-GMO groups led by US Right to Know and funded by the organic dairy company Stonyfield and Ben & Jerry’s spearheaded an initiative to pass a labeling bill in Vermont that would require a prominent GMO label on thousands of products made with crops whose seeds had been genetically modified.

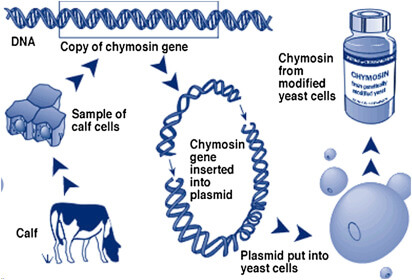

As before though, organic special interests and gross hypocrisy were on display: Vermont’s label came with an exception for cheese. Much cheese is made with a genetically engineered enzyme (90% percent of cheeses and almost all hard cheeses are produced with chymosin that is generated by genetically modified bacteria). This home team exception in a state with a sizable cheese lobby made no scientific sense, underscoring the arbitrary, ideological nature of the labeling enterprise.

The labeling movement was suddenly in a frenzy. In May, hundreds of thousands of citizens marched in 400 or so cities around the world, mostly in the U.S., which they dubbed a March Against Monsanto, the agribusiness which they’d designated the head of the biotechnology monster. They duplicated that feat in October of that year.

The handful of anti-modernity environmental and food sovereignty groups that had been fighting against biotech in agriculture for decades seemed to have connected with a critical mass of consumers to transform into a potent mass movement in the United States. Colorado and Oregon, which had labeling initiatives on the November ballot, were next. Success seemed assured.

But that’s not what happened.

Bubble bursts

Proponents suffered a crushing defeat in Colorado.

In November 2014, the initiatives in Oregon and Colorado, leading comfortably in early polls, all went town to defeat. Without one tiny state backing GMO labels, and fearing labeling chaos, the US Congress jumped in. Washington was awash in lobbyists: pro-organic companies and supporters on one side hoping to dramatically jump their market; farmers, many educators, and the conventional food industry on the other, wary of disrupting the status quo for dubious science.

The air began to leak from the tires of the movement soon after.

In a vote that anti-GMO activists claimed was tainted by lobbyist money, the Vermont law was preempted by the Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act of 2015 (SAFL Act)—or as opponents called it, the DARK Act (Deny Americans the Right to Know. It was shaped by scientists with input from the food and biotechnology industries.

The very passage of the law almost immediately defused the stigma that anti-GMO groups used to connect with a mass base of consumers, most of them poorly informed about the science of genetic engineering. A study on the impact of the passage of the Vermont labeling bill found that a GMO label reduced consumer opposition to GMOs by 20%. While a mile wide, opposition was already an inch deep to begin with. By 2015, Marches Against Monsanto were considerably smaller.

During the same period that the labeling battles were going on, major studies and scientific literature reviews were released affirming the safety and efficacy of biotech crops. This was capped by the release of the National Academy of Science’s exhaustive consensus report on GMOs released in 2016. It soundly confirmed their safety and became the benchmark for mainstream journalists reporting on the issue.

As it turned out, the anti-GMO had seeded their own demise. The labeling battles forced the major global scientific organizations to clarify their positions on GMOs; they all affirmed the scientific consensus that the biotech crops on the market were safe and that the regulatory regimes functioned well in that regard. Nonsense fear claims that seemed plausible in 1997 had been tested in labs and in the marketplace and shown to be false when it came to biotech crops. Meanwhile, consumer-facing products like non-browning apples and potatoes were coming online.

The March Against Monsanto movement died a slow death. One event planned in my hometown of Portland, Oregon in 2017 was cancelled due to lack of interest. The SAFL Act, which finally went into effect January 1 of 2022 after years of tinkering, requires the labelling of modified foods as BE (bioengineered) rather than GMO. As it has turned out, the label didn’t alienate consumers as activists had hoped; rather it largely assuaged their anxiety. Ironically, the passage of the Vermont labeling bill in 2014 set that process in motion.

The New York Times as bellwether

So where are anti-GMO activists today? They are searching for yet another front to fight on, spreading misleading information about CRISPR and other forms of gene editing, which regulators are treating as a distinct category and not as transgenic GMOs, as they do not result from moving genetic material from one species to another—previously the primary complaint of GMO rejectionists. Somehow, moving an unexpressed gene was caricatured as a creating a Frankenfood; with CRISPR, that argument disappeared.

But the fear-laden arguments of biotechnology rejectionists gish galloped to a new, no more scientific, rejectionist talking point. This is an ongoing theme. As the objections of opponents to scientific progress come up against their movement’s expiration dates, those reacting against the new technologies need to find new objections and new areas of contestation, facts be damned.

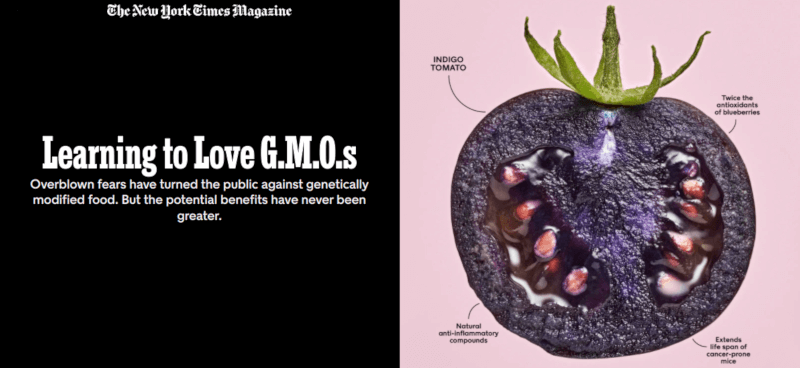

In the United States, the argument that genetically modified crops pose unusual heath or environmental dangers has largely petered out. 2021 marked a kind of cultural watershed moment. In August, an article in The New York Times Sunday Magazine brought home just how rhetorically toothless the anti-GMO movement had become over the previous decade … and how the crank-science wing had become thoroughly marginalized.

The feature, “Learning to Love GMOs”, by Jennifer Kahn, centered on the work of tomato breeder Cathie Martin of the John Innes Centre in Norwich, England. Martin is breeding a high-anthocyanin tomato. The concentration of that antioxidant seems high enough to extend the lives of cancer-prone mice.

The piece traced two parallel narratives. It looked at Martin’s purple tomato and other consumer-centric breeding efforts alongside the psychology behind consumer discomfort with GMOs. Khan wrote, “When cancer-prone mice were given Martin’s purple tomatoes as part of their diet, they lived 30 percent longer than mice fed the same quantity of ordinary tomatoes.” Hope was that a more nutritious tomato would be of greater appeal to consumers than the raft of commodity crops and farmer-centric traits that launched the biotech revolution and spawned the anti-GMO movement.

What’s striking in the piece was how completely Khan dispensed with the central dogma of crop biotech skeptics and activists—that genetically modified crops represent a special category of risk for consumers. Kahn wrote:

The fear of such unforeseen effects — what Jennifer Kuzma, director of the Genetic Engineering and Society Center at North Carolina State University [and a GMO skeptic] calls “unknowingness” — is perhaps consumers’ biggest concern when it comes to G.M.O.s. Genetic interactions, after all, are famously complex. … Megan Westgate, executive director of the Non-G.M.O. Project, echoed this point. “Anyone who knows about genetics knows that there’s a lot we don’t understand,” Westgate says. …

Despite that, plant geneticists tend not to be overly concerned about the risks of G.M.O.s, as long as the modifications are made with some care.

In previous years, an article such as Kahn’s would hew to the journalistic trope of getting comments from both sides, often a pro-GMO “industry spokesperson” and someone who was quite frankly an anti-GMO crank spouting pseudoscience, like the notorious Jeffrey Smith, the author of Genetic Roulette: The Gamble of Our Lives. Smith is a former flying yogic instructor turned director of the dubiously named Institute for Social Responsibility, which appears to consist solely of Smith. Smith’s institute’s sole purpose appears to be providing anti-GMO fear-mongering talking points.

Prior to the labeling losses, Smith was often called for comment by media as authoritative as the New York Times to present the anti-GMO side in a news story; now he’s a laughing stock. [See GLP profile] Media standards have changed. In this case, the Times provided milquetoast and exaggerated quotes about potential unintended consequences from Megan Westgate of the Non-GMO Project which seemed dropped in as boilerplate journalistic balance and little more. Khan then quickly dispensed with reference to the opinions of actual scientists in relevant fields.

Fred Gould, a professor of agriculture who was chairman of the committee that prepared the 600-page [National Academy of Sciences] report … emphasized that many genetic modifications to food are trivial and extremely unlikely to have any measurable effect on people. And even the effects of precursor changes would mostly be slight. “I mean, we’ve been changing all these things already with conventional breeding, and so far we’re doing all right,” he added. “Making the same change with genetic engineering — there’s really no difference.”

The story showed just how far we’ve come in terms of the scientific consensus on GMO safety moving into mainstream consciousness. There had been a time just a few years earlier when claims about unintended consequences and perverse outcomes had a lot more purchase.

The Roundup bogeyman

While failing to generate fear around genetic modification, the anti-GMO movement has been successful in another, destructive way: it’s generated an exaggerated fear about chemicals in our food. As activists realized they were losing the fight to demonize GMOs directly, they switched tactics, going after one of the chemicals long associated with GMOs: glyphosate, the herbicide paired with crops genetically engineered to tolerate spraying so that weeds can be cleared while the crop is in the field. Glyphosate, available in generic form, was long marketed under patent as Roundup and sold by the activist’s devil, Monsanto. The attack on glyphosate/Roundup/Monsanto was actually an attack on GMOs and promotion of organic farming by proxy, as the weedkiller is paired with numerous conventional GMO crops, including corn, soybeans, and cotton.

Glyphosate is the most studied chemical in agricultural history, with more than 3,000 articles in peer-reviewed publications. Every major global and national group that has studied the herbicide, from the US EPA to the European Food Safety Authority to Health Canada to the World Health Organization—has concluded it poses no serious health or environmental risk if used as labeled. In fact, it’s considered less hazardous than any product on the market, including organic alternatives. But activists, knowing how easy it would be to launch and maintain a chemophobia disinformation campaign, believed the public would be vulnerable to its propaganda.

Then they caught a huge disinformation break. In 2015, the WHO-affiliated International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) put out a report identifying glyphosate as a “probable carcinogen” to the applicators who applied it. IARC has reviewed more than one thousand agents to date, and except in one case has found every single one a potential carcinogen. Glyphosate was placed in the same ‘dangerous’ category as getting being a barber, drinking ANY hot beverage, or eating red meat. The evidence on carcinogenicity was less robust than for agents such as bacon, salted fish, oral contraceptives and wine. Even IARC said there was not conclusive evidence that micro-traces of glyphosate in our food supply posed any danger.

Every single agency that had previously issued a summary report on glyphosate—19 of them—reviewed the IARC finding and found it wanting. As Health Canada concluded after its re-review of hundred of studies, including the IARC’s modest review, “No pesticide regulatory authority in the world currently considers glyphosate to be a cancer risk to humans at the levels at which humans are currently exposed.”

But the evidence did not matter; the ambulance chasing fix was in, funded by organic activists and in some cases organic companies. The IARC review, ridiculed by scientists, became the predicate for a series of lawsuits claiming Roundup had caused plaintiffs’ non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The IARC report served as a lifeline to anti-modernity environmentalists. And a goldmine for trial lawyers. By 2017, CNN reported that there were over 800 cancer patients suing then Monsanto, now part of Bayer. By 2019, that number had swelled to 11,000. The prosecution of those cases has been deeply dishonest and misleading but the arguments have prevailed with juries.

Meanwhile, the movement has been putting pressure on governments in Europe and around the world to ban glyphosate. They’ve been successful in Luxembourg, Mexico, Ecuador and Vietnam.

Even as they try to push a narrative about the dangers of glyphosate, independent scientific research keeps finding glyphosate safe. In response, the pseudoscientists affiliated with the movement have shifted their tactics. They’ve tried (but failed) to show that the surfactants (added to make application of glyphosate more effective) pose the real danger. They’ve shifted their focus from cancer claims to gut health and the newly emerging science of the microbiome as the scientific community keeps finding glyphosate to be non-carcinogenic. Or they claim in causes “endocrine disruptions,” a loosey-goosey scientific notion that cannot be quantified, opening many doors into the fear-manufacturing litigation process.

The quest for new avenues of attack is chimerical as old ones are foreclosed by increasingly definitive science.

Europe and Africa in the activist crosshairs

The ongoing controversy is now entrenched in other countries where agricultural biotechnology is relatively new, especially Africa, which depends heavily on Europe for a host of goods, particularly agricultural products. Africa is the most intense battleground. As part of the legacy of colonialism, anti-GMO activist NGOs retain considerable sway across the continent where crop biotechnology holds the most potential to provide struggling farmers leverage for success. Opposition from European-based anti-GMO groups has surged. But the real story across Africa since 2018 has been one of the approval and commercialization of biotech seeds, with recent authorizations of Bt cowpeas in Nigeria, and Bt cotton in Nigeria, Ethiopia, Sudan, Kenya, and eSwatini.

Why the upsurge in anti-GMO activism in Africa? Nothing breeds contempt like success.

In South Africa, the list of available crops places the country squarely in the 21st century:

- Insect-resistant and drought-tolerant maize

- Insect resistant, drought-tolerant, and herbicide-tolerant maize

- Drought-tolerant maize

- Water-efficient maize for Africa

- Drought-tolerant canola

- Herbicide-tolerant canola

- Herbicide-tolerant soybeans

- Herbicide-tolerant rice

- Insect-resistant (Bt) cotton

- Insect-resistant and herbicide-tolerant cotton

Meanwhile, the list of crops under development across Africa is dizzying:

- Insect-resistant (Bt) cowpea

- Cassava resistant to mosaic virus and brown streak virus

- Virus Resistant Cassava for Africa (VIRCA)

- Vitamin-fortified cassava

- Vitamin A-fortified and bacterial wilt-resistant banana

- Potato resistant to late blight disease

- Drought-tolerant and insect-resistant maize

- Water-efficient maize for Africa (drought-tolerant and insect-resistant GE varieties, as well as drought-tolerant conventional hybrids)

- Nitrogen-Efficient, Water-Efficient & Salt-Tolerant (NEWEST) rice

- Vitamin A-fortified sorghum

- Vitamin A-fortified sweet potatoes

- Virus-resistant sweet potatoes

Progress marches on and the forces of reaction do what they do. They react and push back. They look for new areas of contestation but their arguments are always eerily familiar.

The wheel turns

In 2018, I predicted the fading of the anti-GMO movement. In some ways, I feel vindicated. As a mass movement focused on genetically engineered crops, it has collapsed in the United States. The sort of consumers attracted to that narrative are now lining up to buy plant meat Impossible Burgers made with genetically engineered ingredients.

Should we be optimistic that science will prevail and genetically modified crops will get a fair chance in the marketplace?

“I’m personally not as sanguine as you that the anti-GMO movement is fading,” GLP’s executive direct Jon Entine remarked to me. “I see a resurgence in fact. Especially in the UK, Canada, and the EU where gene editing is being debated more openly. Anti-GMO groups are in fact energized as I’ve not seen them in years. They are attacking gene drives used to control disease-vectoring mosquitoes, once again playing the unintended-consequences-species-extinction-butterfly-effect card. They, in turn, use that to broadly tar CRISPR in all of agriculture as many gene drives are gene-edited.”

In fact, while the progress in Africa is heartening, internationally the anti-GMO movement has found a footing on multiple fronts. The global phalanx of institutional opposition to genetic engineering may be getting a second wind, even as a new more consumer-facing array of biotech crops gains acceptance. Self-named green activists in the US, Canada and Europe are using their familiar fear-mongering techniques to scare people about gene drives, and by proxy, all of genetic engineering.

Personally, I’m not as skeptical as Entine. The global trend, from vaccines to crops, is toward embracing biotechnology. At a deeper level, I believe the ratchet moves in one direction over the long haul and that direction is towards science and innovation. At least that’s what I see when I look at the sudden surge of progress in Africa and Southeast Asia on genetically modified crops after decades of obstruction.

Death and dissolution are the inevitable fate of any reactionary movement with a narrow scope of interest. In 1991, the development economist and political theorist Albert O. Hirschman published the book The Rhetoric of Reaction. The book argues that conservative political movements—or in this case reactionary liberals— have a discernible pattern in making the case against reforms and innovations. They pursue three strategies:

- Argument from Futility

- Argument from Perversity

- Argument from Jeopardy

In Part II, we will explore the reactionary rhetoric of the anti-GMO and related movements.

Marc Brazeau is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on agricultural biotechnology. He also is the editor of Food and Farm Discussion Lab. Follow him on Twitter @eatcookwrite