Is there any evidence for an association?

What they are

Artificial sweeteners, or sugar substitutes, are food additives imparting a sweet taste to foods or drinks without adding calories. They are 200-700 times sweeter than sugar and work because the body cannot break them down into energy – resulting in no calories.

The main artificial sweeteners in use today are:

- Aspartame (brand name is Equal, blue packets)

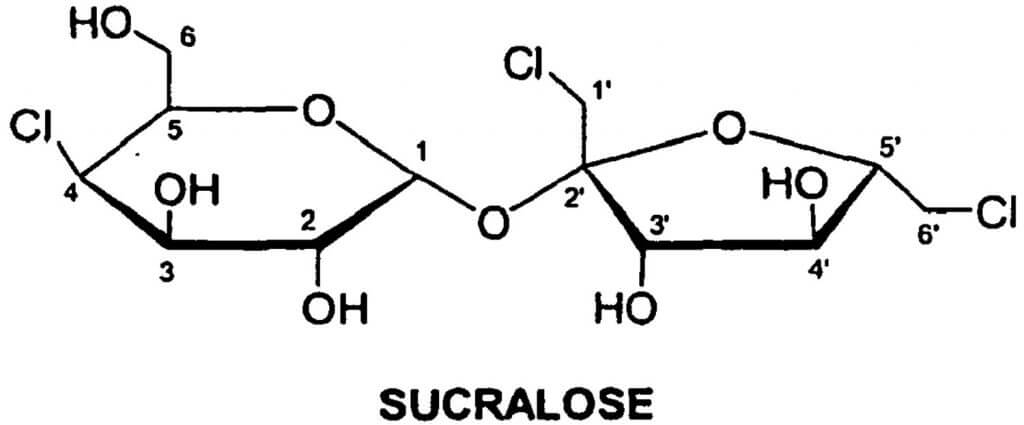

- Sucralose (brand name is Splenda, yellow packets)

- Saccharin (brand name is Sweet n’ Low, pink packets)

Artificial sweeteners are used in many products, including diet soda and the ubiquitous little yellow and pink packets found in every US coffee shop. However, they have a long and controversial history over their possible association with cancer.

The search for sweet-tasting substances

Before the 1950s, the main reason for using artificial sweeteners was cost; it was often cheaper than sugar. Saccharin was first produced in 1879. In 1907, the Director of the Bureau of Chemistry (the forerunner of the FDA) stated that it was an illegal substitution for sugar. It was so popular that Theodore Roosevelt answered him by saying, “Anybody who says saccharin is injurious to health is an idiot,” promptly ending the Director’s career.

In 1977, the FDA tried to ban saccharin based on studies showing bladder cancer in rats. Public opposition was intense, and instead, the FDA mandated new labeling,

“This product contains saccharin which has been determined to cause cancer in laboratory animals.”

In 2000, the label was dropped. Subsequent studies indicated that the bladder cancer found in rats was due to a mechanism that was not relevant to humans. Saccharin was delisted from the National Toxicology Program’s (NTP) Report on Carcinogens as no longer a “substance reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen.”

Another artificial sweetener, cyclamate, was approved by the FDA in 1951. It was banned in 1970 after a study found an increased rate of bladder cancers in rats. However, further evaluation caused the FDA to reverse its position again, stating that there is no evidence that cyclamate causes cancer in rats or mice. While cyclamate remains banned in the US, it is a sweetener in at least 130 other countries.

In the 1950s, however, artificial sweeteners became a diet aid, continuing through the present day.

How safe are they?

Aspartame

Aspartame entered the US food market in 1981. The FDA reviewed a large number of studies in the approval process for aspartame. More recently, studies in laboratory animals have not shown an increased cancer risk, even at very high doses, including a study in mice done by the NTP. A study in children did not show any association between aspartame consumption and brain cancer.

However, stories about its ability to cause cancer keep appearing in the media. This is not limited to the general press; just a few months ago, the following article was published in a scientific journal: “Aspartame and cancer – new evidence for causation” The report says there are new findings that confirm that aspartame is a carcinogen in rodents.

What are these new findings? These are old findings from studies done in 2006 and 2007 by the Ramazzini Institute. [1] The Ramazzini Institute has been repeatedly criticized for its lack of quality control. This first came to light over ten years ago when it became apparent that no matter what substance was tested by the Ramazzini Institute, the results were always positive for carcinogenicity.

Several organizations have reviewed the findings from the Ramazzini Institute on aspartame and concluded that they were without merit. In 2013, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) concluded that due to uncertainties in the tumor diagnosis and health issues with the experimental animals, there was insufficient evidence to conclude that aspartame caused tumors in these studies.

Another article evaluated the reliability of the available studies investigating possible links between aspartame and cancer. The Ramazzini Institute was the only organization among the nine that was scored “not reliable,” while all the others were found to be “reliable with restriction.”

These issues with the Ramazzini Institute are neither new nor unique to aspartame. In fact, in 2010, the EPA put four of its ongoing chemical assessments on hold while it reviewed data from the Ramazzini Institute used in their assessments. The EPA no longer uses data from Ramazzini.

Sucralose

Sucralose is the newest of the major artificial sweeteners, entering the market in 1998. It differs from the other artificial sweeteners in that it is made from natural sugar. It can be used in a granulated form that allows it to be substituted for sugar in baking. As with aspartame, the FDA approval of sucralose involved reviewing a large number of studies, with no indication that it caused cancer. Studies since that time have also revealed no cancer risk.

Once again, the Ramazzini Institute raised concerns over the safety of sucralose with the 2016 publication of a study that concluded that sucralose caused blood tumors in mice. A year later, EFSA reviewed the research and concluded that the available data did not support the conclusions of the authors due to

- the lack of a dose-response relationship

- no identifiable mode of action

- and lack of data indicating a cause-effect relationship.

Conclusions

The issue for the reader who wants to be informed is how to make sense of the constant flow of contradictory reports of cancer-causing substances. It is extraordinarily difficult.

Let me offer two tangible steps that every consumer can take. “Google” the authors of the study and the associated funding organizations. This often brings up surprising and enlightening facts! Also, look at the Conflict of Interest or Competing Interests section found at the end of every reputable study. It tells you who is funding the research and the relationship between the authors and funding organizations.

Today’s readers are inundated with headlines intended to scare, cause fear, or cause you to stop using a helpful product or eat what you enjoy. As a reader, you must be skeptical. In the case of artificial sweeteners, there is no evidence that they pose a cancer risk.

Notes:

[1] The Competing Interests section of the article notes: “There is no financial conflict of interest. Both of the authors are members of the Scientific Advisory Board to the Ramazzini Institute.”Susan Goldhaber, M.P.H., is an environmental toxicologist with over 40 years’ experience working at Federal and State agencies and in the private sector, emphasizing issues concerning chemicals in drinking water, air, and hazardous waste. Her current focus is on translating scientific data into usable information for the public.

A version of this article was originally posted at the American Council on Science and Health and has been reposted here with permission. The ACSH can be found on Twitter @ACSHorg

This article previously appeared on the GLP on September 21, 2021.