Reading a book can have a profound impact on the person reading it. While that might not seem terribly surprising to anyone who’s ever gotten lost in the fictional world of their favorite author, researchers at Emory University have concluded that reading a novel physically changes your brain. But it seems they may have reached in their conclusions.

“Most people can identify books that have made great impressions on them and, subjectively, changed the way they think,” the authors wrote. “We sought to determine whether reading a novel causes measurable changes in resting-state connectivity of the brain and how long these changes persist.”

Using a technique known as “resting state fMRI”, which scans a person’s brain while they lie still in the scanner, researchers analyzed data from 19 volunteers for 19 days. For the first five visits, participants did nothing. For the next nine days, the volunteers read a chapter from the Robert Harris novel Pompeii the night before and then completed a short quiz about the book’s content and answered questions about how the book made them feel. Then on the final five days, participants were scanned while once again doing nothing, allowing the researchers to look for lingering effects of the reading days.

Researchers found that compared to the days on which participants didn’t read the novel, they were able to identify “three independent networks that had significant increases in connectivity.” Two of these networks involved brain “regions previously associated with perspective taking and story comprehension.” These networks showed a decay in connectivity after the participants were done reading the novel.

The third network showed that connectivity continued past the experiment. The researchers suggested that “reading a novel invokes neural activity that is associated with bodily sensations,” since this part of the brain is often activated when people read about the sense of touch.

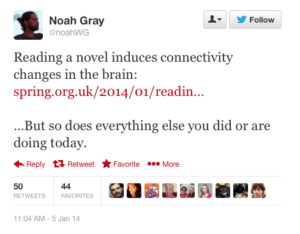

From these results, the researchers concluded that reading a novel does, in fact, physically change your brain. However, as Nature editor Noah Gray noted on Twitter:

Gray isn’t the only one questioning the leaps taken by the researchers.

Science writer Christian Jarrett immediately questioned the study in Wired:

So, there’s a new study out (pdf) that’s used brain scanning to investigate how reading a book changes your brain. It tripped my skeptic’s radar right away because our brains are changing all the time, and pretty much anything we do influences those changes. And we already knew the power of reading novels, didn’t we? You follow a story, meet characters, learn things. Nonetheless the media are all over this neuroscience study, hyping and misinterpreting the results. Among the most daft was “Reading a good book may make permanent changes to your brain” from the UPI news agency. That’s quite a leap given that the study only looked at brain changes up to five days after participants had finished reading a novel.

Jarrett went on to explain that the study simply contained too many unknowns to be taken seriously as a scientific study:

It’s important to note that the researchers didn’t ask the participants to do any psychological tests after the book reading, so they don’t know the functional significance of these brain changes. Other issues to bear in mind: We don’t know what the participants were doing with their minds while they were in the scanner (more criticism of resting-state scans here); we don’t know what they were getting up to during the 19 days of the study when they weren’t at the lab or reading the book; it’s very hard to tell what influences on resting brain connectivity were due to reading per se and which were due to the quizzes conducted just before the scans. There’s also no information in the paper on the size of the connectivity changes. There’s no control group, so we don’t know if spending time in a bar with friends (or any other activity) each evening prior to the scan would have had a larger or different effect than reading a novel. We also don’t know much about the participants – whether they read regularly or if this was the first novel they’d read in years.

Fellow science writer Alex Snapp agreed with many of Jarrett’s criticism in Forbes:

This is a prime example of both how much we know about neuroscience and how little. We know that reading changes the brain, in part (per Gray) because everything changes the brain. But are there changes to the brain specific to reading a book? What kind of changes are they? How long do they last? What is their significance? These questions are a lot harder to answer. But along the way, we might learn some interesting things.

As Snapp points out, there is still much we don’t know about neuroscience. Studies like this one, though they raise interesting questions, serve to confuse and limit further understanding, especially when their conclusions reach beyond the results they provide.

Additional Resources:

- When it comes to human brain, size isn’t everything, New York Times

- A clearer picture of the mind in real-time brain imaging, Medical Xpress

- A virus hitched a ride in our ancestors genome, and changed human brains forever, National Geographic