ProMED relayed this news to its global subscribers two days later. Many of us read it and thought, hmm, odd. By that time, because the Pomeranian’s owner had been sick for two weeks and tested positive herself, the dog was quarantined in a government-run facility. Throughout his quarantine period, the dog “remained bright and alert with no obvious change in clinical condition,” by one report, but his clinical condition already wasn’t too good. Anyway, he survived to bark again.

The second known pet was a young German shepherd, also in Hong Kong, also from a household with a human case.

Next it was cats. A group of scientists in Wuhan began promptly in January 2020, as the outbreak among humans made headlines, testing the blood of domestic felines for signs of the virus. They gathered data through March and posted a preprint on April 3. This team included researchers from a college of veterinary medicine, and maybe they were simply following a hunch. They took blood samples from a total of 102 cats, including abandoned creatures harbored at animal shelters, cats at pet hospitals, and cats from human families in which Covid-19 had struck. (They also looked, for purposes of comparison, at 39 cat samples drawn before the outbreak, all negative.) They found evidence of the virus in 15 cats and, in 11 of those, strong evidence of antibodies capable of neutralizing the virus.

“Our data demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 has infected cat population in Wuhan during the outbreak,” they wrote in the preprint. By the time their study appeared in a journal, other cats elsewhere had become infected.

A cat in Belgium tested positive. A cat in France tested positive. Another study from China, done by experiment at a veterinary institute in Harbin, in the north, showed that cats inoculated with SARS-CoV-2 became infected and could transmit the virus to other cats through the air. A cat in Hong Kong tested positive. A cat in Minnesota, a cat in Russia, two cats in Texas.

In Italy, a cat named Zika began sneezing, then tested positive, evidently having caught the virus from her human, a young doctor working on Covid. In Germany, a 6-year-old female cat at a retirement home in Bavaria tested positive by throat swab after her owner died of Covid-19. In Orange County, New York, just up the Hudson River from New York City, a 5-year-old indoor cat started sneezing, coughing, draining from her nose and eyes, about eight days after her person developed similar symptoms. She tested positive.

Domestic cats aren’t social creatures in the ecological sense; they don’t aggregate in dense populations (except amid the pungent households of obsessive cat hoarders and overgenerous rescuers), so the opportunities for cat-to-cat transmission tend to be low. But many a house cat, once it gets outside, interacts with mice in the barn, the shed, or the backyard.

Those mice generally belong to two groups, house mice (Mus musculus) and deer mice (several species within the genus Peromyscus). Deer mice are well documented as hosts of hantaviruses and the Lyme disease bacterium, and recent laboratory work shows them susceptible to infection with SARS-CoV-2. A mouse can carry the virus for as long as three weeks and transmit it efficiently to other mice.

Deer mice are the most abundant (nonhuman) mammals in North America. It may be only a matter of time before SARS-CoV-2 gets into a population of deer mice, from a cat, and begins mouse-to-mouse transmission in the wild. More on this theme, below, when we get to the mink and the white-tailed deer.

Among felids infected with SARS-CoV-2, it hasn’t been just the domestic kitties: A tiger named Nadia, at the Bronx Zoo in New York, appeared sick and tested positive for the virus, presumably transmitted by one of her zookeepers. It seems she wasn’t alone. According to a statement from the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS, within the U.S. Department of Agriculture), Nadia’s testing came after several lions and other tigers at the zoo showed signs of respiratory distress. Within weeks, four more of the Bronx tigers and three lions tested positive. A puma (an American cougar) at a zoo in South Africa tested positive. A female snow leopard and two males, at the Louisville Zoo, in Kentucky, started coughing and wheezing, then tested positive.

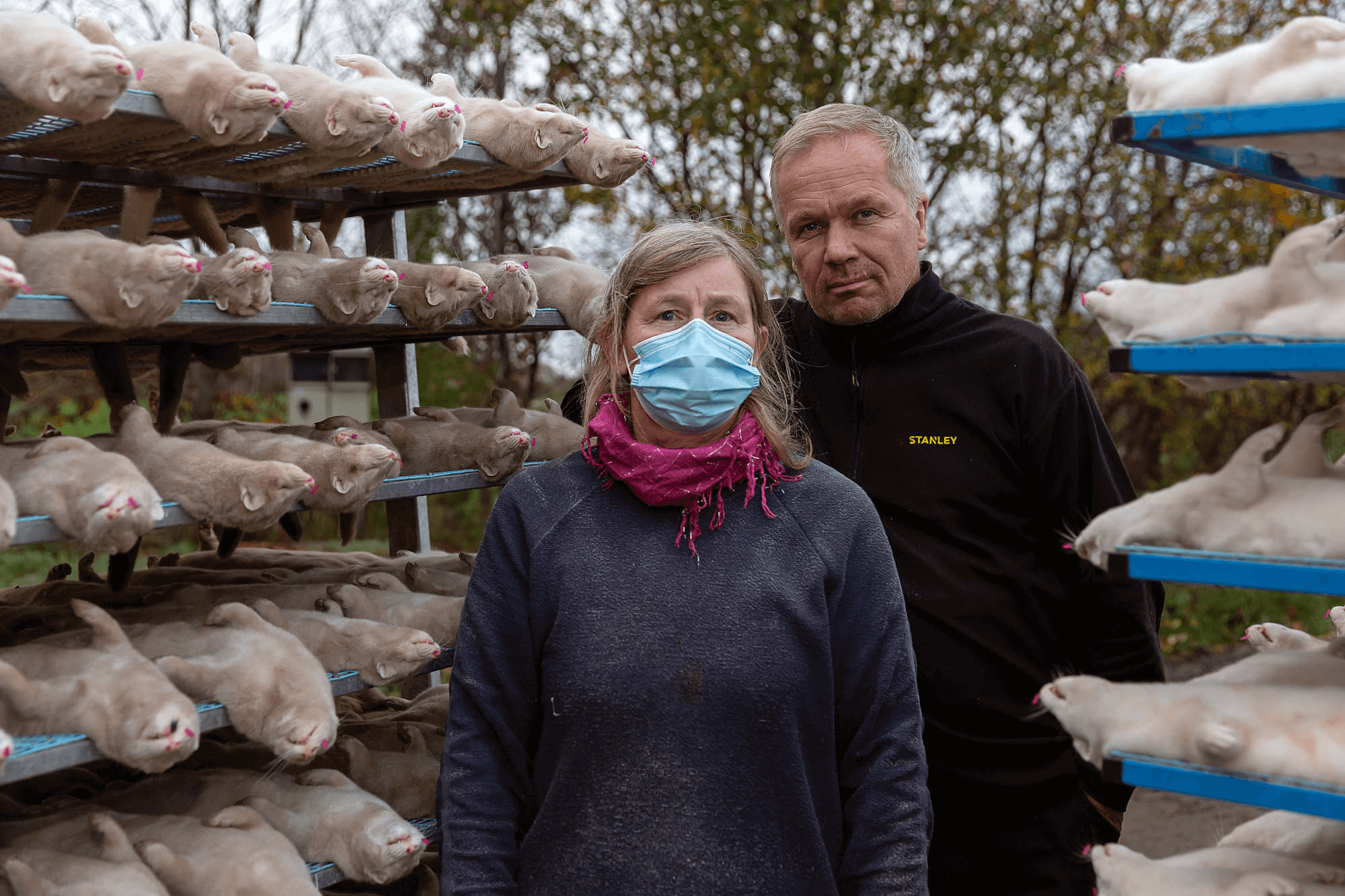

In the Netherlands, during the spring of 2020, SARS-CoV-2 began showing up among farmed mink. Those outbreaks carried large economic consequences as well as public health implications, because the mink were held in crowded conditions, raised in the thousands for their fur, and they proved very capable of transmitting the virus, both from mink to mink and possibly (with human help) from farm to farm.

The first detected cases occurred on two farms in the province of Noord-Brabant, which is in southern Netherlands along the Belgian border. “The minks showed various symptoms including respiratory problems,” according to a statement from the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature, and Food Quality.

Several roads were closed, and a public health agency advised people not to walk or cycle in the vicinity of those farms. But the virus spread quickly, soon affecting 10 farms, then 18 farms, then 25 farms by the middle of July 2020.

The Netherlands contained a lot of mink: roughly 900,000 animals at 130 farms. These were American mink (Neovison vison), like virtually all farmed mink, preferred for the richness of their fur; they belonged to the mustelid family, which includes also the pine marten, the European polecat, and the Eurasian badger.

Dutch exports of mink fur earned about 90 million euros annually in recent years, according to the Dutch Federation of Pelt Farmers. The industry was controversial — fur farming of all sorts is controversial in much of Europe, on grounds of animal welfare — and the Netherlands had already moved toward ending it by 2024. Now that happened more quickly, under government orders to cull all the animals on affected farms, in advance of the usual November doomsday for farmed mink, and not to restock.

By the end of June 2020, almost 600,000 Netherlands mink had been slaughtered. The virus wasn’t innocuous in mink; it caused respiratory symptoms and some mortality, which was what triggered testing and detection of the virus on those first two farms. But it didn’t kill mink as quickly as the culling did.

A team of Dutch scientists investigated the outbreaks, between April and June, and eventually published a paper in Science. The senior author on that study was Marion Koopmans, head of virology at the Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam. “In February, because of the dog infection in Hong Kong,” she told me, “we had a meeting.”

Koopmans, an expert on zoonotic viruses, interacts regularly with the National Public Health Institute, the Veterinary Health Institute, and an independent organization, farmer-supported, called the Animal Health Service. By late spring, everyone was aware that SARS-CoV-2 had appeared not just in one or two Hong Kong dogs but also in domestic cats, tigers, and lions. Among humans, it was raging in Italy, and the Netherlands was suffering its first wave, with almost 40,000 cases by the end of April and a gruesomely high case fatality rate.

“We were ramping up human diagnostics,” Koopmans said — the labs at her center, as well as veterinary labs in the system. Then came a couple of dead mink, submitted for necropsy. “And I said, ‘Hey, well, what the heck. Let’s also test these mink.’” It was done at the same veterinary lab that had jumped in to do human diagnostics. Bingo.

As the mink outbreaks turned up on one farm after another, and the human pandemic intensified, Koopmans and her colleagues found time and resources to study the animal phenomenon, which would have implications for public health as well as for the fur industry.

They sampled both mink and people on 16 farms, finding not just lots of infected mink but also 18 infected people among farm employees and their close contacts. The team sequenced samples and saw that the viral genomes in people generally matched the genomes in that farm’s mink. This and other evidence suggested not just human-to-mink transmission starting each outbreak, and mink-to-mink transmission keeping the outbreaks aflame, but also possibly mink-to-human transmission. That last point was ominous and I’ll return to it.

In mid-June, it was Denmark’s turn. “A herd of mink is being slaughtered at a farm in North Jutland after several of the animals and one employee tested positive for coronavirus,” according to a report in The Local, an English-language online media service. That farm was quarantined, and all 11,000 animals would be killed. The news fell heavily because Denmark, with roughly 14 million mink on more than a thousand farms, produced a large portion of the world’s pelts, and the quality of Danish pelts was considered supreme.

The virus spread quickly that summer. By early October, 41 Danish farms had recorded outbreaks and authorities spoke of culling a million mink. This was optimistic. By mid-October: Sixty-three farms and plans for culling 2.5 million mink. But that too was just a beginning.

In the meantime, health officials in Spain ordered the culling of 93,000 mink on one farm, after determining that “most of the animals there had been infected with the coronavirus,” according to Reuters. Mink tested positive on a farm in Italy. In Sweden, a veterinary official visited a mink farm on the southern coast, reporting, “We tested a number of animals today and all were positive.”

Mink at two farms in Utah tested positive, and then came some worse news. Veterinary officials from the U.S. Department of Agriculture revealed that a wild, free-ranging mink in Utah had also tested positive. The sequenced virus from that wild mink matched the virus in mink on a farm nearby, so the wild individual had presumably been infected by an escapee — or by schmoozing with captives nose-to-nose through a fence.

This raised a concern well beyond the economics of fur: the prospect of SARS-CoV-2 gone rogue into the American landscape. In the lingo of disease ecologists: a sylvatic cycle.

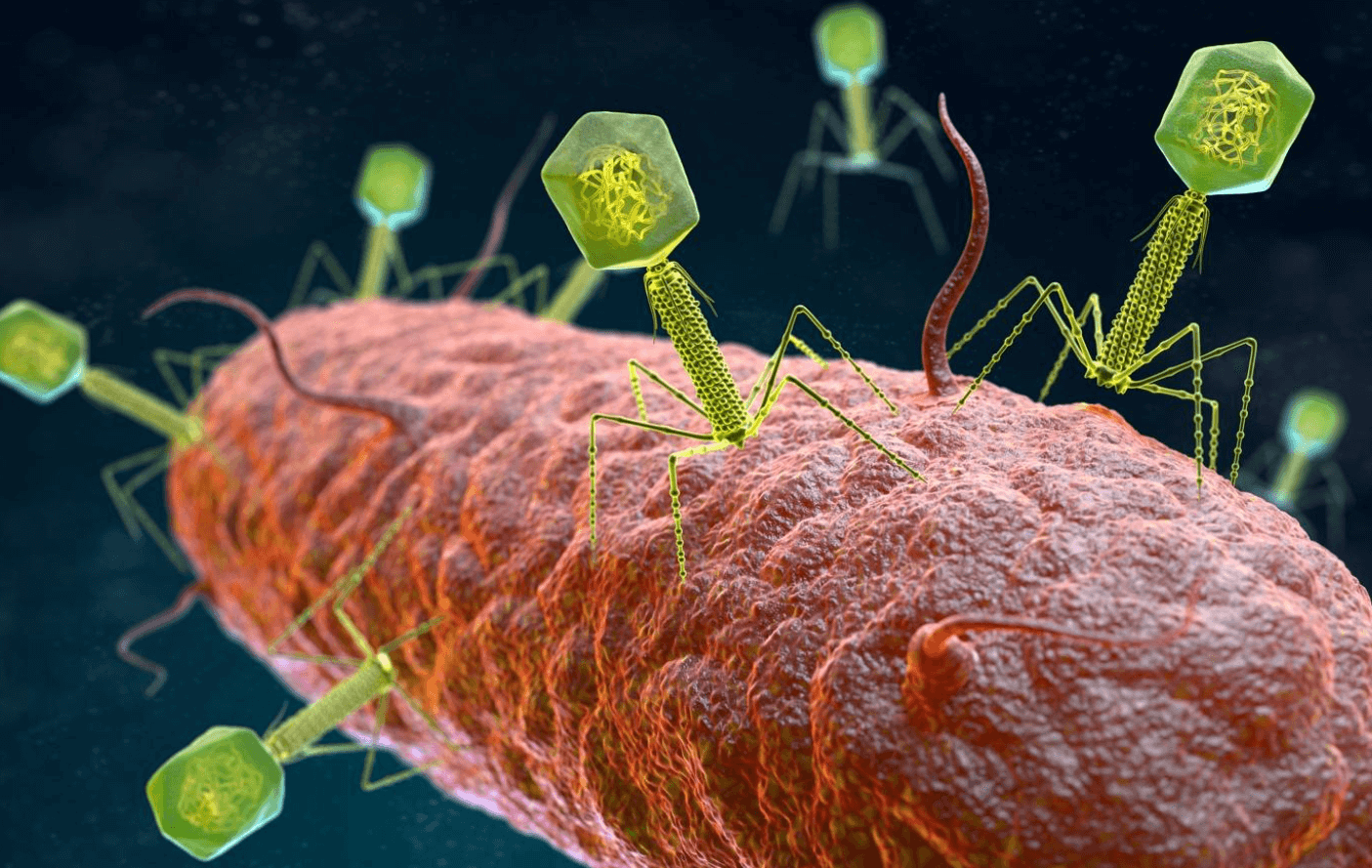

That term comes from the Latin word sylva, meaning forest. A virus with a sylvatic cycle is two-faced, like a traveling salesman with another wife and more kids in another town. Yellow fever virus, for example: Transmitted by mosquitoes, it infects humans in cities (the urban cycle) when the right mosquitoes are present, but it’s broadly enough adapted to infect monkeys also, and it does that in some tropical forests (the sylvatic cycle), circulating in monkey populations.

Yellow fever can be eliminated in cities by vaccination and mosquito control, but whenever an unvaccinated person goes into a forest where the virus circulates, that person can become infected, return to the city, and trigger another urban cycle, if some mosquitoes are still there to help. Yellow fever virus has never been eradicated, and travelers to many tropical countries are still obliged to be vaccinated, because the sylvatic cycle will persist, and threaten another urban cycle, until you kill every mosquito or vaccinate every monkey.

Now transfer the concept to SARS-CoV-2 and consider: If the world’s forests or other natural ecosystems contain populations of wild animals in which that virus circulates, either because they are the original reservoir hosts (horseshoe bats in southern China?) or because they have become infected by contact with humans (mink in Utah? deer mice in Westchester County?), then there is no end to Covid-19. (There is probably no end to it regardless, but that’s another matter.)

There is no herd immunity where there is a sylvatic cycle. An unvaccinated person has contact with an infected wild animal (a mink, a cougar, a monkey, a deer mouse) during some activity (hunting, cutting timber, picking fruit, sweeping up urine-laced dust in a cabin) and becomes infected with the virus, potentially triggering a new outbreak among people.

You could vaccinate every person on Earth (that’s not gonna happen) and the virus would still be present around us, circulating, replicating, mutating, evolving, generating new variants, ready for its next opportunity.

The chance of a sylvatic cycle in Europe, possibly also derived from mink, is elevated by the fact that many mink escape from farms — a few thousand every year in Denmark alone. Although not native to the European continent, these American mink have established themselves as an invasive population in the wild, their presence reflected in the numbers taken by hunters and trappers.

About 5 percent of the farmed Danish mink that escaped in 2020, by one expert’s estimate, were infected with SARS- CoV-2. Mink tend to be solitary in the wild, but obviously they meet to mate, and as both predators and prey within the food chain, they come in contact with other animals.

Atop the list of other creatures that might be susceptible to a mink-borne virus are their wild mustelid relatives, the pine marten, the European polecat, and the Eurasian badger.

On Nov. 5, 2020, another bit of disquieting news came out of Denmark. The government announced severe restrictions on travel and public gatherings for residents of North Jutland — that low and tapering island curled like a claw toward southwestern Sweden — after discovery that a mink-associated variant of the virus, containing multiple mutations of unknown significance, had spilled back into humans. Twelve people had it.

This variant became known as Cluster 5, because it was fifth in a series of mink variants; but it was the first to be detected in humans. It carried four changed amino acids in the spike protein, raising concern that it might evade vaccine protections when vaccines became available. That’s it, we’re done, said the government statement: all remaining mink would be culled. The mink industry in Denmark was over.

But the rigorous shutdown, the tracing of cases, and the other control measures pinched that variant to a dead end. Within two weeks, a Danish research institute announced that the Cluster 5 lineage seemed to be extinct, at least among humans. Whether it survived in the wild, among escaped mink or their native relatives on the Danish landscape — pine marten, European polecat, Eurasian badger — is another question.

Through the last months of 2020 and well into 2021, reports of SARS- CoV-2 in nonhuman animals continued, sporadic but notable. A tiger at a zoo in Knoxville, Tennessee, tested positive. Four lions of the beleaguered Asiatic population, at a zoo in Singapore, started coughing and sneezing after contact with infected zookeepers.

Two gorillas, also coughing, at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. The two gorillas recovered within weeks, although not before one animal, a 48-year-old silverback with heart disease named Winston, had been treated with monoclonal antibodies. Winston also got cardiac medication and, as a precaution against secondary infection with bacteria, some antibiotics. If he had been a wild gorilla in an African forest, he might well be dead. Then again, if he had been a wild gorilla, free of zookeepers, he probably wouldn’t have caught this virus.

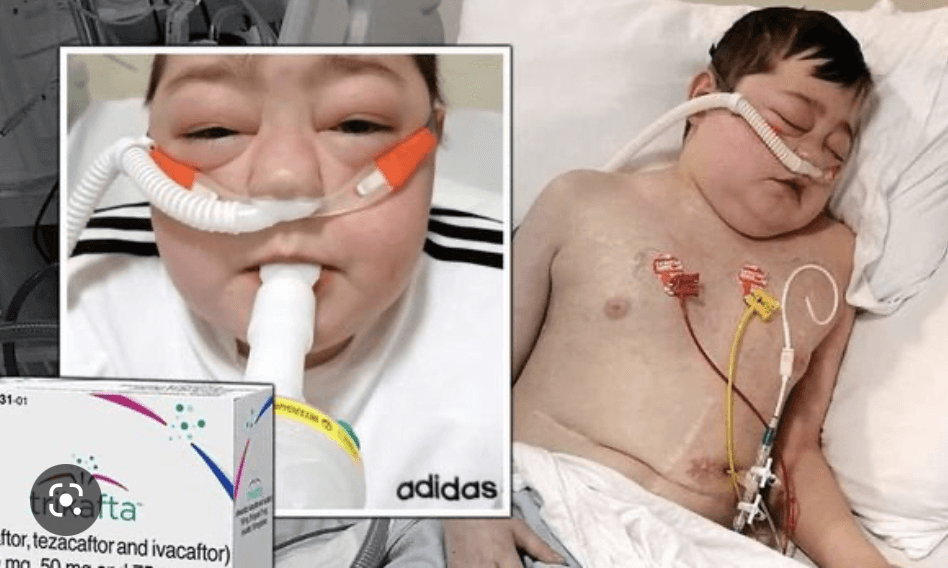

In October 2021, SARS-CoV-2 reached the Lincoln Children’s Zoo, in Lincoln, Nebraska, infecting two Sumatran tigers and three snow leopards. This zoo proclaims a mission to enrich lives, especially children’s lives, through “firsthand interaction” with wild creatures, under controlled and educational circumstances. It’s a meritorious goal, but as we’ve all learned, close encounters in the time of Covid carry risks. These snow leopards were less lucky than the three in Louisville a year earlier. In November, despite treatment with steroids, and antibiotics against secondary infection, all three died.

Meanwhile, of course, people were dying too. By Oct. 31, 2021 — the second Halloween of the pandemic — the state of Nebraska had recorded 2,975 Covid fatalities. For the United States on that date, the cumulative toll was 773,976 dead. Throughout the world, SARS-CoV-2 had killed more than 5 million humans. In the small nation of Belgium, with a total population less than 12 million, one person in 10 had been infected with the virus, the curve was rising steeply, and 26,119 people had died.

In December, also in Belgium, two hippopotamuses at the Antwerp Zoo tested positive. They were luckier than the Nebraska snow leopards or the 26,119 dead Belgians, showing no symptoms beyond runny noses (more runny than usual for hippos), but were put into quarantine.

Other news in late 2021 brought the prospect of a sylvatic cycle from possibility to reality. Scientists at Penn State University, working with colleagues at the Iowa Wildlife Bureau and elsewhere, reported evidence of widespread SARS-CoV-2 infection among white-tailed deer in Iowa. Experimental studies had already shown that captive fawns, inoculated with the virus, could transmit it to other deer. This new work went much further, revealing that wild deer had become infected, somehow, from humans — and not just a few deer. SARS-CoV-2 was rampant throughout the Iowa deer population.

That trend began slowly, after the beginning of the pandemic, but by the final months of 2020 it was overwhelming. The team’s trained field staff collected lymph nodes from the throats of almost 300 deer, mostly free-living animals on the Iowa landscape, a lesser portion contained within nature preserves or game preserves — none of them artificially infected by experiment.

The sampled deer had been killed by hunters or in road accidents by vehicles. The field staff dissected out the lymph nodes, in connection with an ongoing surveillance program for another communicable illness, chronic wasting disease. The deer sampled early in the study, during spring and summer 2020, were clean of SARS-CoV-2. (Iowa’s initial wave among humans rose in April.) The first positive animal didn’t turn up until September 28, 2020.

After that, it was like popcorn in a hot pan. Over a seven-week period during hunting season, in late 2020 and early January 2021, the team sampled 97 deer, among whom the positivity rate was 82.5 percent. The research continues, with a second phase of sampling, and if that percentage holds anywhere near steady (confidential updates suggest it will), it’s startling evidence of sylvatic SARS-CoV-2 in Iowa.

Iowa is not alone. A different study, done by federal wildlife officials from APHIS, looked for the virus among white-tailed deer in four other states, using blood serum samples rather than lymph nodes. These samples dated from early 2021.

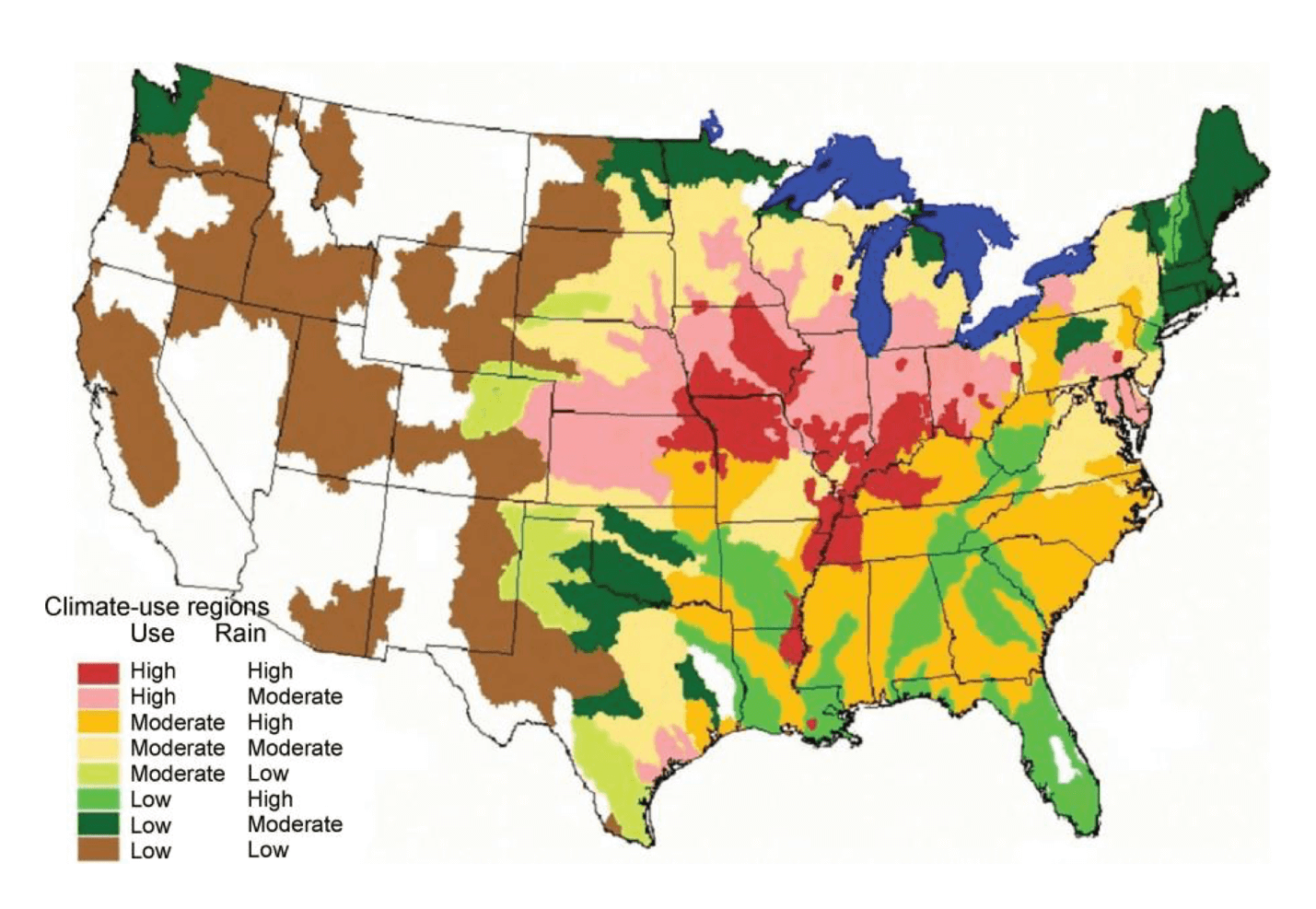

Illinois’s deer were the most Covid-free, with only a 7 percent rate of infection. If you had announced that statistic alone, at the time, it would have seemed shocking. Seven percent of Illinois deer have Covid? But among whitetails sampled in New York, the rate was 31 percent infected; in Pennsylvania it was 44 percent; in Michigan, it was 67 percent.

The United States presently contains an estimated 25 million white-tailed deer, and no one has informed them that SARS-CoV-2 is uniquely, peculiarly well adapted for infecting humans.

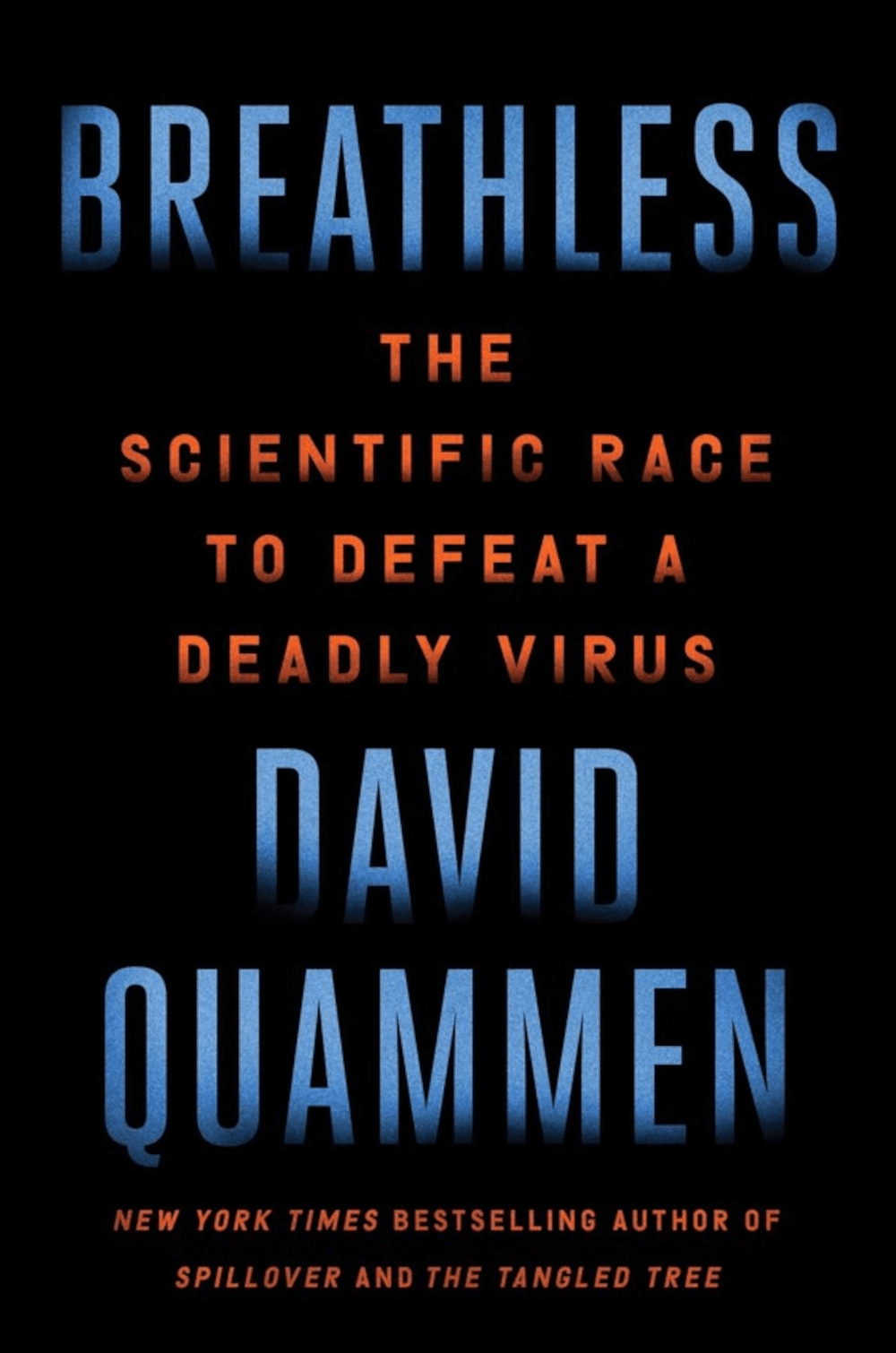

David Quammen has written for The New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, The Atlantic, National Geographic, and Outside, among other magazines, and is a three-time winner of the National Magazine Award. He is a founding member of Undark’s advisory board. Follow David on Twitter @DavidQuammen

A version of this article appeared originally at Undark and is posted here with permission. Check out Undark on Twitter @undarkmag

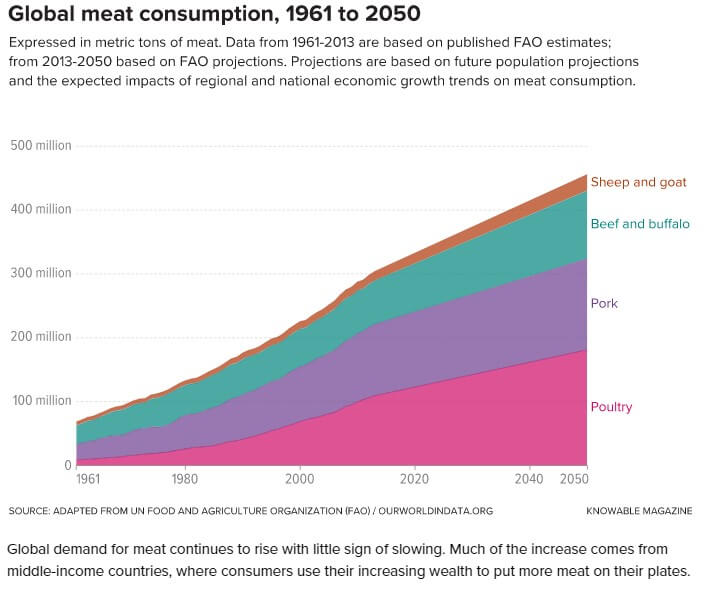

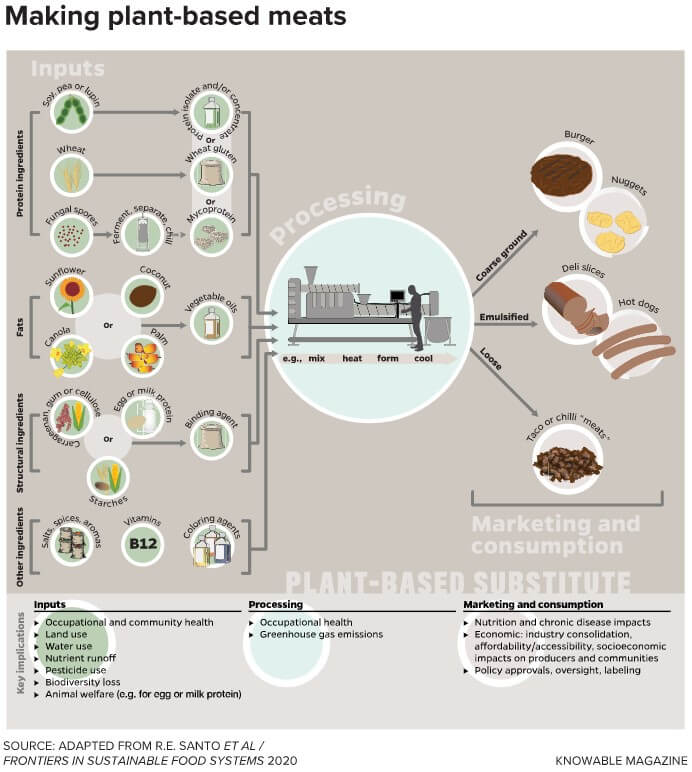

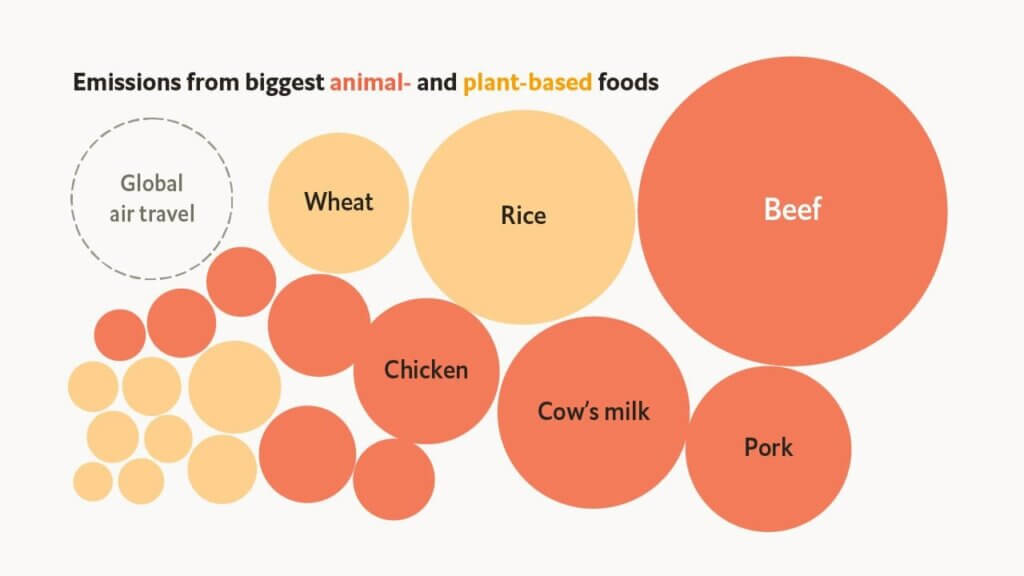

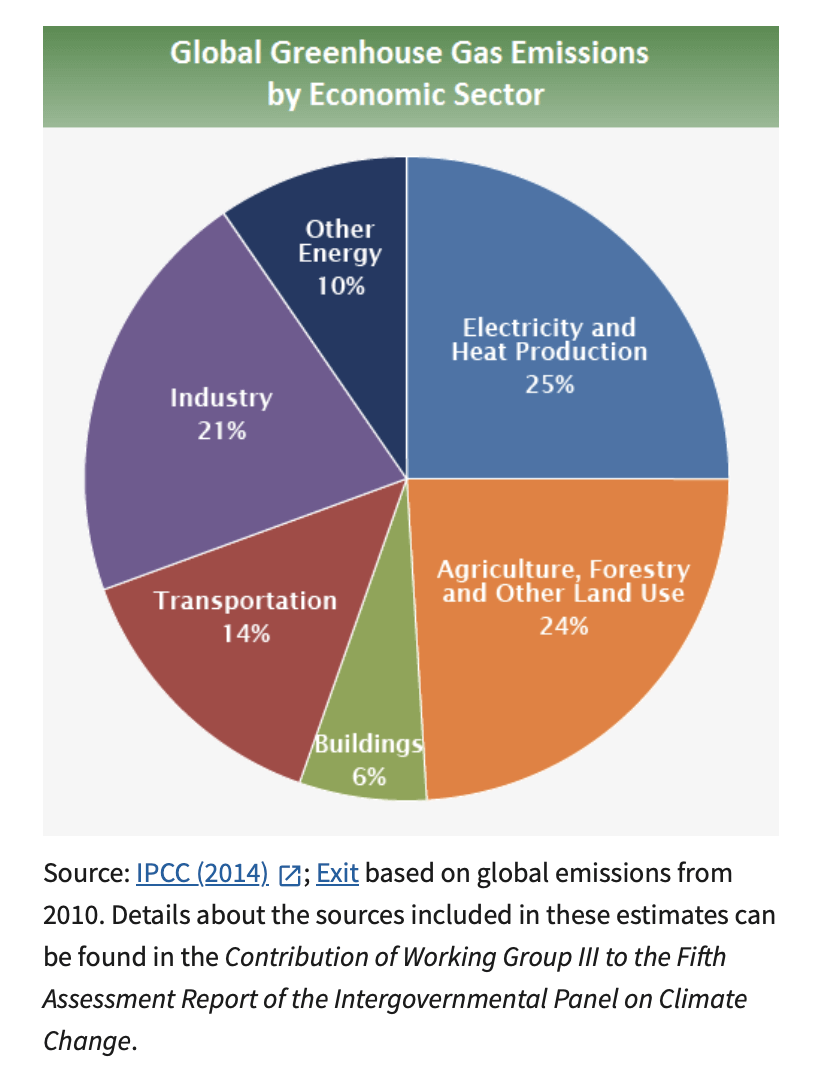

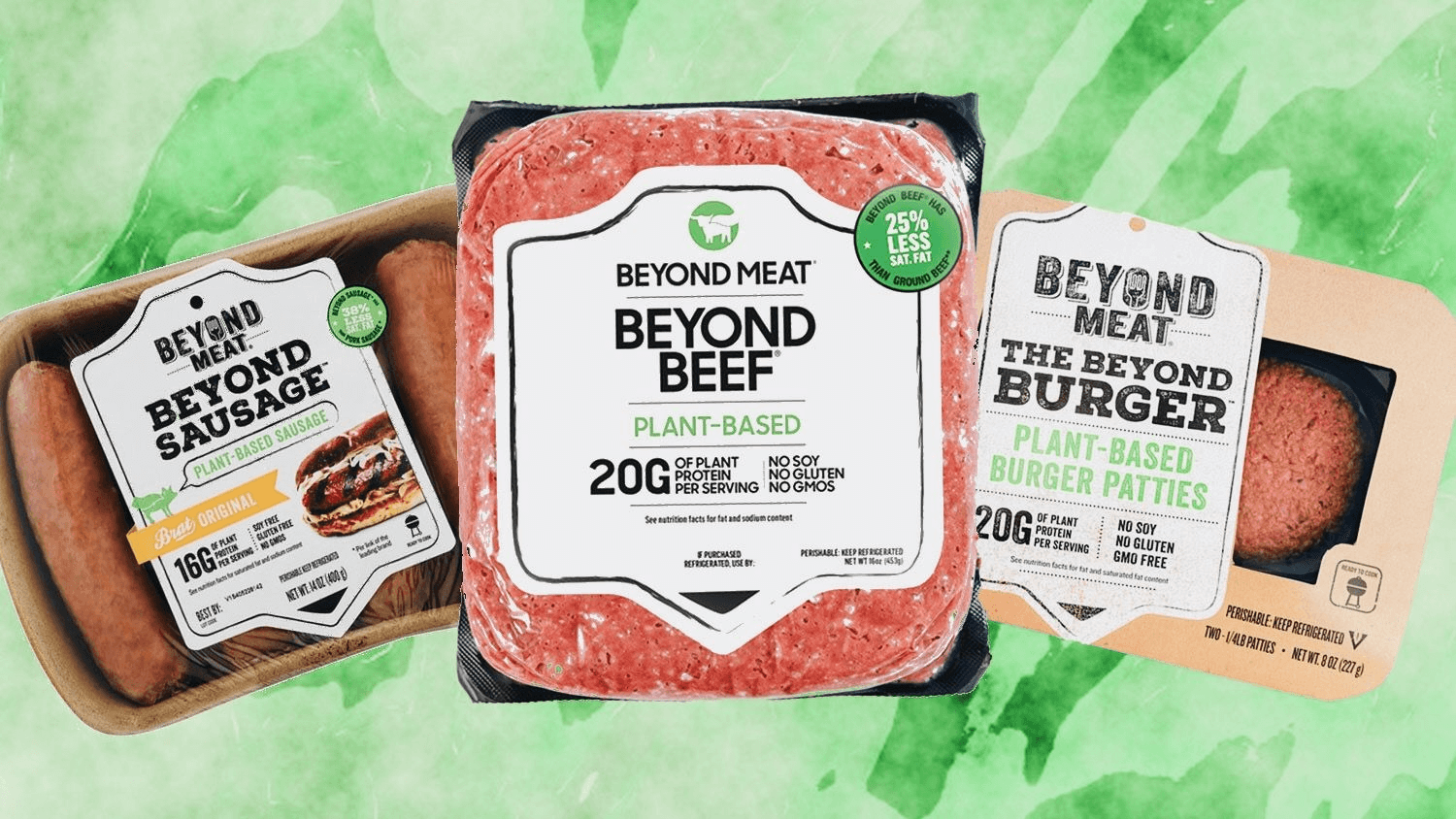

That’s a big reason there’s such a buzz today around a newcomer to supermarket shelves and burger-joint menus: products that look like real meat but are made entirely without animal ingredients. Unlike the bean- or grain-based veggie burgers of past decades, these “plant-based meats,” the best known of which are

That’s a big reason there’s such a buzz today around a newcomer to supermarket shelves and burger-joint menus: products that look like real meat but are made entirely without animal ingredients. Unlike the bean- or grain-based veggie burgers of past decades, these “plant-based meats,” the best known of which are