In countries such as the U.S. and Canada, the term “children’s food” conjures images of milk, sugary cereals, yogurt tubes, and chicken fingers. Advertisers, restaurants, and media market these items as kid-friendly fare that’s convenient, palatable, fun, and supposedly “healthier” than adult foods.

The rationale for feeding children these foods is their need for extra nutrients and because, in some cultures, kids are thought to be “picky eaters.” But how much of this is rooted in biological reality, and how much is a product of cultural notions?

In my new book, Small Bites: Biocultural Dimensions of Children’s Food and Nutrition, I explore kids’ diets through an evolutionary lens and anthropological research in several countries. I sift through the differences between biological needs and social constructs, exploding myths about children’s food and eating. I demonstrate how the category of kids’ food is an invention of the modern food industry that began in the U.S. and is now pervasive around the world. In addition, I describe cross-cultural practices that may offer more nutritious, enjoyable, and equitable models for feeding children.

Do children require special diets?

Not long after vitamins were first discovered in the 1910s, people became gripped with “vitamania.” Food and drug producers, medical professionals, and some media outlets convinced many parents that their kids weren’t getting enough vitamins from their regular diets, so they needed to give them supplements like cod liver oil and yeast cakes.

Today the fear of children not getting adequate nutrients is encapsulated in new, ultraprocessed products. Enter “toddler milk” or “growing-up milk.” This powdered product is designed for children 1–3 years of age and is marketed to promote healthy brain growth because it contains DHA (docosahexaenoic acid, a type of omega-3 fat). In the U.S. from 2006 to 2015, the amount spent on advertising toddler milk saw a fourfold increase while sales multiplied 2.6 times.

But paradoxically, toddler milk may do more harm than good. It undermines breastfeeding for up to two years (a practice that is recommended by the World Health Organization), it’s expensive, and it contains added sugar, possibly distracting toddlers from eating nutritious foods. Plus, there is no evidence that toddler milks are more nutritious than regular milk or other healthy foods.

Credit: Jim Watson via AFP andGetty Images

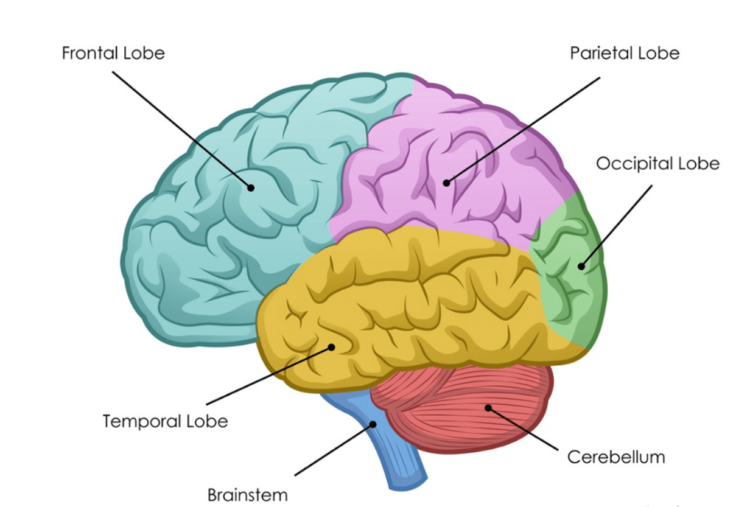

From conception to adolescence, children do require high-quality food to maintain their nutritional well-being. During the first year of life, babies triple their weight and increase their length by more than 50 percent. The next highest period of growth velocity occurs during adolescence. The brain grows even faster, and by 7 to 11 years of age, the brain has almost completed its volumetric growth.

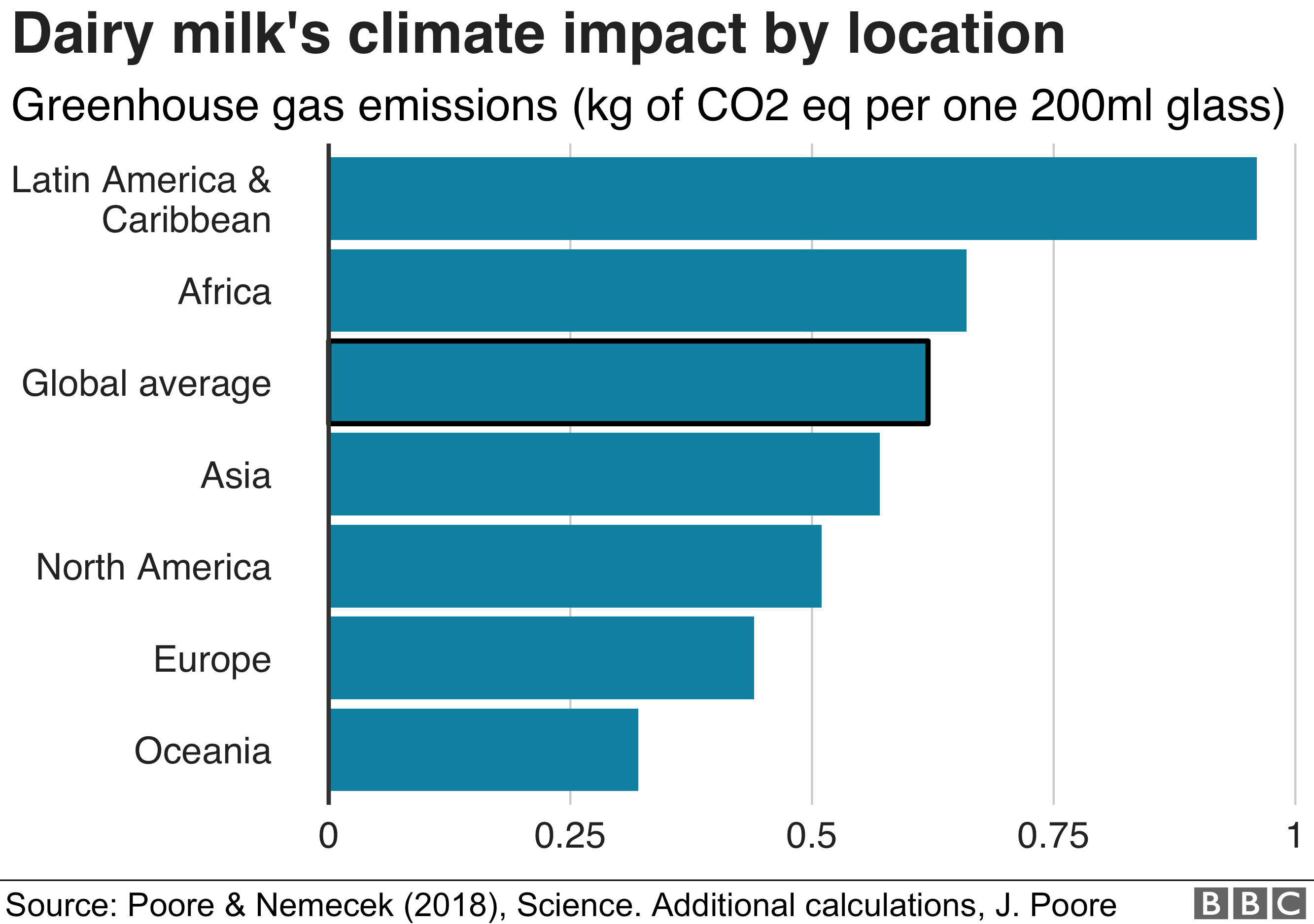

Rapid growth requires fuel (energy) from protein, carbohydrates, and fat, as well as vitamins and minerals. Calcium, for example, is needed in abundance (relative to body weight) during childhood and adolescence. This is why milk, which is rich in calcium along with many other nutrients, is promoted for children, though it is not the only way to obtain calcium for optimal growth.

So, while children have special nutritional requirements that change with each stage of development, they do not need special foods. In fact, such foods may be hurting kids. But even if kids don’t nutritionally need their own menu, do they just naturally want certain foods like buttered noodles and cheese sticks?

Is picky eating biological or cultural?

From 6 to 12 months of age, when children are completely dependent on their caregivers, they don’t discriminate much in their eating. From 13 months to 6 years, however, they become quite discerning. The fear of new foods (or food neophobia) may be a built-in survival mechanism while they are discovering what is edible and inedible.

Picky eating is distinct from food neophobia. Picky eating includes the rejection of new foods but goes beyond that to the rejection of large categories of foods, even familiar ones at different times, based on characteristics like color or texture. Picky eaters usually eat inadequate amounts and types of foods. This behavior may continue into adolescence and even adulthood. I argue that though neophobia in early childhood is universal, picky eating is culturally constructed.

While no studies compare the prevalence of picky eating in childhood worldwide, there is some evidence to demonstrate that picky eating may be a “culture-bound syndrome” specific to American cultural norms, though certainly not limited to the United States.

In China, for example, finicky eating is a recent and variable phenomenon. Traditionally, children ate what their parents ate. The term for children’s food in China, ertong shipin, did not appear in the dictionary until 1979, and it was not until the rising affluence of the 1980s that children’s food became part of popular Chinese culture. Even so, parents in China report that picky eating is more common in urban and suburban areas than in rural places.

In Nepal, I researched children’s food among families in urban Kathmandu and those living in a rural village in the Himalayas. I collected data from parents about the diets of their children under 5 years of age and found that children mostly ate the same food as their older family members. But in Kathmandu, unlike in rural villages, children were regularly fed commercial products such as Nestlé’s Cerelac (instant cereal) and sweet, packaged biscuits.

One place where picky eating is by and large not condoned is France. Children in France are expected to try new foods. They eat mostly what adults do and mostly like it too.

I studied elementary school lunch programs in Paris, interviewing school administrators, nutritionists, and parents, plus sampling lunches in a selection of schools. Children in France have very structured mealtimes: breakfast, lunch, goûter (afternoon snack), and supper. This structure is also reflected in school meals, where children all consume the same lunch, consisting of an entrée (usually a vegetable), a main course—meat/fish and vegetables, or a vegetarian dish—followed by cheese/yogurt/fruit and accompanied by bread and water. Meals are subsidized and geared to income, and menus indicate which foods are organic and/or locally procured.

France is quite serious about teaching children food culture. Each fall, the country holds la Semaine du Goût, during which schoolchildren spend the week visiting food artisans and cooking and tasting different foods from local regions to learn to appreciate French cuisine.

If studies show, then, that children aren’t biologically driven to be picky eaters, and they don’t require special meals for their nutritional well-being, why is the idea that children require their own category of food so pervasive?

The industrial food system and kids’ eating habits

Before food was industrialized, children’s food did not exist as a distinct category, apart from weaning foods like mashed carrots. Then the industrialization of food began around 1870 in the United States and intensified after 1945.

It was initiated when companies began patenting a process of milling that produced whiter, longer-lasting, and less nutritious flour. Subsequently, corporations like Coca-Cola and Kellogg’s began branding foods. Whole foods were simplified and became more processed through the addition of salt, sugar, fat, and chemical additives to extend their shelf lives and thus increase profit.

As families became smaller and the focus on children intensified in the 20th century during the “century of the child,” children became lucrative for the food industry. This is because older children had their own money to spend on food, and children of various ages increasingly began to influence their parents’ purchases. As a result of these and other factors, children and adolescents in the U.S. now get 67 percent of their calories from ultraprocessed foods such as frozen pizza, industrial bread, and candy.

One of the most common—and harmful—ingredients in children’s foods is sugar. Epidemiological evidence links high sugar consumption with numerous health issues, such as heart disease, obesity, and diabetes.

There is a growing recognition that advertising targeting children is contributing to malnutrition in kids.

Children are particularly vulnerable to the sugar-saturated industrial food system due to their fondness for sweet tastes. Studies of babies indicate they always respond more positively to sweet foods, and children have a higher preference for sweet tastes that remains elevated through childhood and declines during mid-adolescence to adulthood.

There is likely an evolutionary advantage to preferring tastes that signal nontoxic foods such as fruits, especially at a stage in life when one is tasting many foods for the first time. In addition, sweeter foods are high in energy, so humans may have evolved cravings for sweet things that correspond to higher energy needs during growth and development.

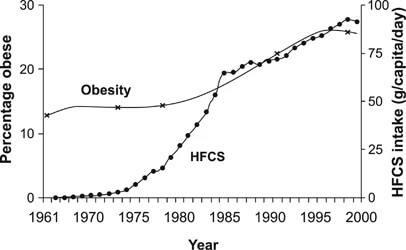

While the heightened desire for sweetness during childhood may be biologically driven, people are not programmed to eat sugar in the quantities they often do today. Prior to its mass production beginning in the 19th century, sugar was not available or affordable for most people. Since the development of high-fructose corn syrup, sweeteners have become cheaper and more ubiquitous than ever.

Two ultraprocessed and often sugary foods that have become sine qua non fare for children are breakfast cereals and snack foods. Kids can prepare and eat both relatively independently, since neither requires a stove. And young children can easily pack and open snack foods like yogurt tubes, fruit rollups, and grain bars, making them convenient meals on the go.

Companies market cereal and snack foods to kids using cartoon and TV or movie characters, a form of “eatertainment” that can help parents who may be struggling with work/home balance to prepare convenient foods for their picky eaters. In addition, advertisers endow these cereals and snacks with “health halos” because they are made from ingredients such as dairy, fruit, or whole grains, or are fortified with vitamins and minerals.

Despite these claims, studies have consistently shown that diets high in ultraprocessed foods contribute to obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors in children, plus increase the risk for cardiovascular diseases and cancers in adults.

There is a growing recognition that advertising targeting children is contributing to malnutrition in kids. As a result, Sweden and Quebec have banned all advertising to children, while the U.K. eliminated the advertising of unhealthy foods online and before 9 p.m. on television. But in the rest of Canada and in the United States, the monitoring of children’s food advertising is voluntary and subject to guidelines only.

Models of feeding kids in different cultures

Many nations prioritize feeding children in ways that not only attend to their nutritional needs but also consider food equity. This is usually accomplished through school meal programs. An estimated 388 million children in low-, middle-, and high-income countries worldwide receive school meals.

These programs are paramount for many low-income and working families who rely on the meals to reduce household labor, particularly for women, and subsidize food costs. The necessity of these programs has been highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many schools closed, and children’s nutritional well-being suffered greatly. However, the quality of these programs varies widely, and some have been criticized for their nutritional deficits and for stigmatizing children who receive subsidized meals or who cannot pay for their food.

Exemplary school meal programs—such as those in Brazil, Colombia, Finland, France, Italy, and Japan—provide affordable lunches for children that not only offer pleasurable and nutritious dining experiences but also teach children about national gastronomic culture and support local agriculture.

In Brazil, for example, school meals are entirely funded by the government, menus are developed by nutritionists, and schools must buy at least 30 percent of their produce from small-scale farms, preferably locally. In Finland, all children attending pre-primary to secondary education (around ages 6 to 18) are entitled to free school meals.

As these programs and numerous studies demonstrate, children’s food doesn’t need to be special or different from adult food. But it must be prioritized with special care in order to sustainably and healthily nourish children and future generations.

Tina Moffat is an associate professor and chair of the department of anthropology at McMaster University in Canada who studies the social and cultural determinants of maternal-child health and nutrition. She is a co-editor of the edited volume Human Diet and Nutrition in Biocultural Perspective: Past Meets Present (with Tracy Prowse). Moffat is the past president of the Canadian Association for Biological Anthropology. Follow her on Twitter @TinaMoffat3

A version of this article was posted at Sapiens and is used here with permission. Check out Sapiens on Twitter @SAPIENS_org

Stanley Miller wasn’t the first to think of how to recreate life’s beginnings. Soviet biochemist

Stanley Miller wasn’t the first to think of how to recreate life’s beginnings. Soviet biochemist

Since the moment you were born, your brain has been developing, Marte Roa Syvertsen tells sciencenorway.no.

Since the moment you were born, your brain has been developing, Marte Roa Syvertsen tells sciencenorway.no.