A new paper describing the community of human placenta microbes has generated a flood of journalistic supposition and health advice that has galloped way ahead of the data in the paper. It’s just one example of another round of what the well-known evolutionary microbiologist Jonathan Eisen calls “overselling the microbiome.”

To be fair to the journalists, many of their claims are drawn from statements by the paper’s lead author, Kjersti Aagaard, of the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. In interviews, Aagaard has willingly speculated that there is a relationship between oral health and a healthy pregnancy, including prevention of preterm birth. Yet the paper provides no evidence to support that contention.

The study notes a long-known association between periodontal disease in a pregnant woman and premature birth. It also suggests ways in which mouth infections might result in inflammation elsewhere in the body and could contribute to premature birth. However, it also says explicitly “this study is not able to address the relationship between periodontal disease and the placental microbiome.”

Eisen, who frequently hands out Overselling the Microbiome Awards at his blog Tree of Life, has launched an unusually deep and devastating critique of the reporting on this paper. Eisen is particularly incensed about news stories in Science and the New York Times, usually both reliable sources on new research and its implications.

Eisen objects to a lot in the Science story, by Jocelyn Kaiser, especially the quotes from Aagaard that claim the study re-emphasizes the importance of oral health during pregnancy and even before, that this may be a burden for low-income women, and that urinary tract infections (or the antibiotics used to treat them) may alter the microbiome in unhealthy ways, which Eisen says is “misleading and not supported.” It is all speculation, Eisen declares, “and speculation is fine -IF YOU TELL PEOPLE YOU ARE SPECULATING.”

Placenta and mouth microbiomes

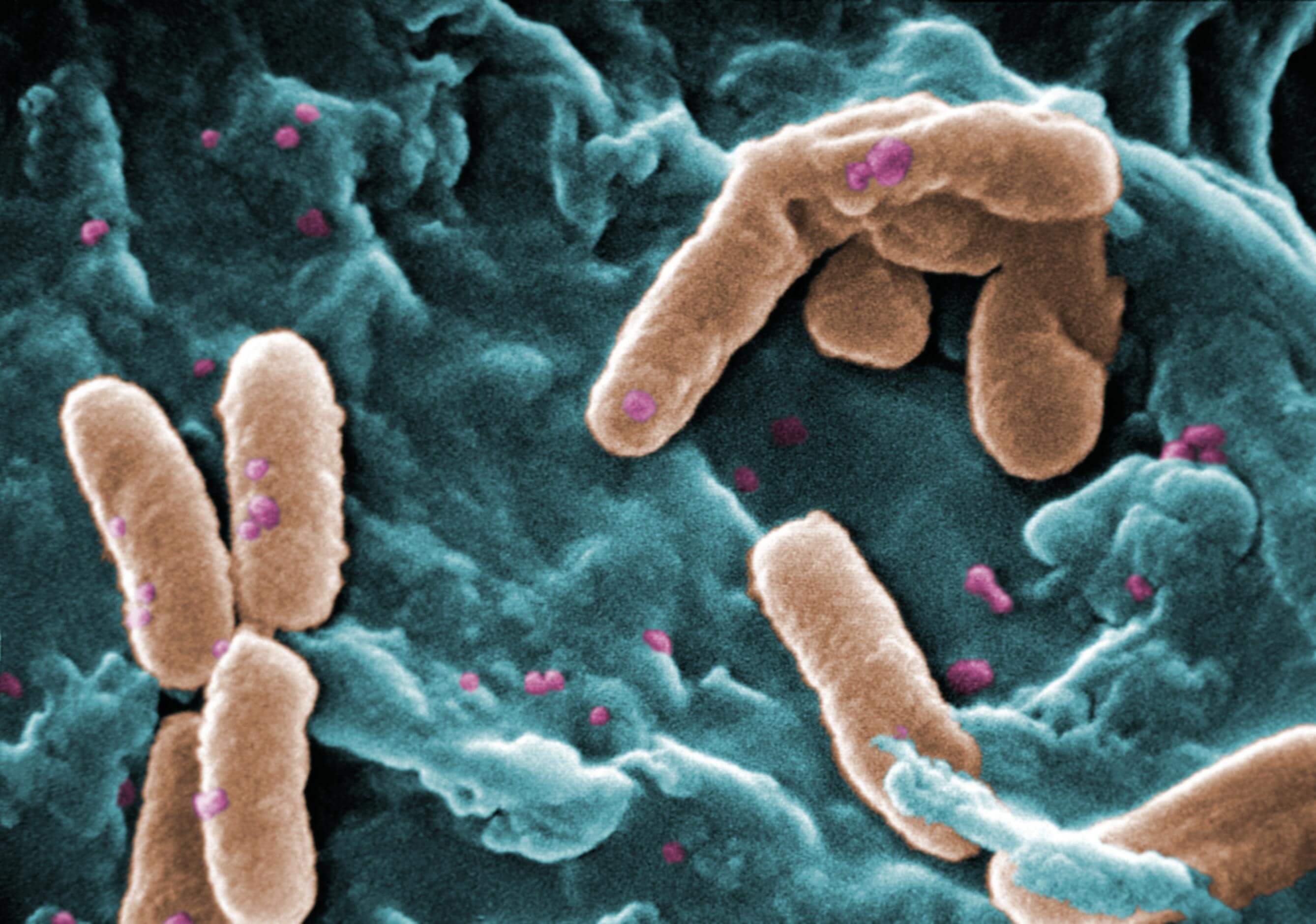

The paper reported identifying DNA from nonpathogenic microbes in placentas recovered from 320 pregnant women at birth. The placental microbe community was not similar to normal microbial communities in most other parts of the body, such as the vagina, gut, and nose. Instead, to the researchers’ surprise, the small placental microbe community resembled some microbes normally found in the mouths of nonpregnant subjects. Similarities between placental microbes and mouth microbes have been shown in mice, too.

For financial reasons, the study did not compare placental microbiomes with various microbial communities elsewhere in each of the 320 pregnant subjects. Instead the comparisons were carried out on microbiomes from nonpregnant subjects enrolled in the Human Microbiome Project, a reference population. Thus it is not known whether the microbiome of the placenta from a particular baby resembled the mouth microbiome of his or her mother. Only 1 woman of the 320 had been diagnosed with periodontal disease.

The New York Times piece by Denise Grady explains the research “may help explain why periodontal disease and urinary infections in pregnant women are linked to an increased risk of premature birth.” Eisen agrees that they may help explain too-early deliveries, but points out that infection may also have no connection to premature birth at all. He lists 18 factors known to affect premature delivery and asks, “are we now discounting the years and years of work on this and going whole hog into proposing a new cause without any evidence?”

A chief aim of the paper is to help define the pathways by which newborns acquire their own microbiomes. The researchers propose that one route may be from the mother’s mouth to the fetal placenta through the mother’s blood. The Times piece says the study suggests that babies may acquire an important part of their normal gut microbes via the placenta. Eisen’s response: “No. Nothing in this study showed any connection between what is in the placenta and what is in the babies’ guts. None.”

The Times piece also speculates that the study may be of comfort to women who have had caesarean deliveries, which have been said to deprive infants of microbes they would normally acquire on passage through the vagina. It quotes Aagaard thus, “I think women can be reassured that they have not doomed their infant’s microbiome for the rest of its life.” Eisen retorts, “Wow. Now we have gone from “if further research confirms” to just flat out reassuring women who have had C-sections that there are no effects on the microbiome.”

Overselling the microbiome?

Eisen has been objecting to the overselling of the microbiome for years. He’s not the only critic. Just a few days ago Knight Science Journalism Tracker Paul Raeburn complained about a Huffington Post piece. It claimed that the human microbiome is the best predictor of lifelong health, and that autism, allergies, asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes and obesity are all tied to the health of the victim’s resident microbe communities.

Possible connections between these conditions and the microbiome are being studied, but there’s no final word on any of them. A report from the American Society for Microbiology released early this year noted, “Any suggestion that complex conditions like diabetes or obesity can be explained simply by the composition of the microbiome is likely to be misleading.”

The hype is being stoked by commercial interests in selling microbes as the route to health, interests that go way beyond yogurt. The hope is to turn bugs into proprietary pharmaceuticals. Early this month the trade publication Fierce Biotech reported on a new partnership between pharma giant Pfizer and the biotech start-up Second Genome. The two will study the relationship between the microbiome and the metabolic profile, and their target is obesity. This is Second Genome’s second big deal; last year it teamed up with Johnson & Johnson to work on inflammatory bowel disease.

I have a smidgen of sympathy for the microbiome oversellers because they are up against a century and a half of convincing the medical establishment, and then the people, that microbes are the cause of disease, food spoilage, and divers other evils. It was a hard slog at first, but ultimately completely effective. Only in the last decade has the idea that microbiomes are “natural” and mostly good for you begun to percolate into general understanding.

Many have still to get the message. The Atlanta Journal put this headline on the Associated Press story about the placenta research study: “Bacteria live even in healthy placentas.” That headline is chock-full of inaccurate assumptions and prejudices, the basic one being that bacteria are bad by definition. The idea that very few microbes are harmful and a great many are necessary for life is still quite new. Furthermore, it requires jettisoning the many decades people have dedicated to absorbing the contrary message.

Adventures in the skin trade

Will the Microbes are Good for You campaign be helped or hindered by last week’s article in the New York Times Magazine? That’s the one recounting a writer’s experience with skipping showers and shampoo and deodorant for a month, ostensibly in the interests of science.

Julia Scott was testing a new cosmetic product containing billions of cultivated Nitrosomonas eutropha, an ammonia-oxidizing bacterium commonly found in dirt and untreated water. The point was to spray it on her skin and hair twice daily in an effort to establish colonies of N. eutropha. The bugs were supposed to gobble up the ammonia in her sweat and prevent olfactory offense despite her lack of bathing.

It worked, mostly, although she found her greasy hair troubling. More interesting to most readers, I imagine, was her report that her skin was much improved–smoother, softer, less dry, breakouts gone, tiny pores. An interesting dilemma, this cosmetic tradeoff. Is better skin worth occasional smelliness and greasy hair? My first thought: If you sprayed it just on your skin, could you improve your complexion but still wash your hair?

AO+ Refreshing Cosmetic Mist containing N. eutropha is in the vanguard of microbial products from the cosmetic industry. But its manufacturer AOBiome (AO = ammonia oxidizing) isn’t really interested in cosmetics at all. The biotech startup wants to get into using microbes to treat skin ailments like eczema.

Scott reports that AOBiome has chosen the cosmetic route for its initial foray in order to get around the much tougher and much longer regulatory requirements for medical applications. It is hoping to use revenue from the Mist to finance research on drug products.

The company, and other investigators Scott describes, are hoping for great things from microbial skin therapies. Revolutionary acne treatments, for instance. The dream is that microbes can “help us diagnose and cure disease, heal severe lesions and more. Those with wounds that fail to respond to antibiotics could receive a probiotic cocktail adapted to fight the specific strain of infecting bacteria. Body odor could be altered to repel insects and thereby fight malaria and dengue fever. And eczema and other chronic inflammatory disorders could be ameliorated.”

It may take a long time and a lot of overselling the microbiome to turn people accustomed to the routine of daily shower and shampoo back into the Great Unwashed. The Great Unwashed is what we were even here in the US not so long ago, before the bathroom became near-universal. (I speak here of a room where people bathe, not the more common meaning of the word “bathroom.”)

For the hundreds of thousands of years of human existence before the 20th century passion for cleanliness, we hardly ever bathed. But we certainly didn’t deliberately establish bacterial colonies on our persons either. Skipping showers and shampoos and deodorant is perhaps “natural.” Twice-daily sprays of N. eutropha are not.

Will the Times Magazine piece hasten the day when applying microbes will be a usual part of the grooming ritual? One can hardly imagine a more splendid venue for a product launch; AOBiome must be ecstatic. Jonathan Eisen and his Overselling the Microbiome Awards will likely soon be busier than ever.

Tabitha M. Powledge is a long-time science journalist and a contributing columnist for the Genetic Literacy Project. She writes On Science Blogs for the PLOS Blogs Network. New posts on Fridays.

N. eutropha is found in soil and in unpurified water. So, uh, maybe it was *completely* natural to actually have it on your skin? Maybe it was completely natural for humans, in the early years, to bathe in this unpurified water, maybe even use soil as a cleanser (like many other animals do)? … Just sayin’.

Exactly. How Fn short sighted. I am a biome skeptic myself, but I can see through my confirmation bias. I have never use a **iotics product, until recently. I just try to eat well. However, the washing off eutropha makes sense. Further, I tried the AO spray and it has helped, demonstrably, with eczema. Color me a biome skpetic still, but happy to have learned of eutropha.

I do still shower and just respray. Same logic as the writer.