Editor’s note: This article is part three of a three-part series by Marc Brazeau on his 2018 predictions on food, farming and GMOs. Read part one and part two.

2017 brought numerous instances of fissures and fault lines in the various coalitions that mostly work together to maintain the status quo in the food system.

Farmer groups are allied with both the input companies – from John Deere to BASF to Monsanto – as well as the meat processing and commodity companies – Tyson, Smithfield, ADM, Cargill against consumer and environmental groups. On some issues, I think the agvocates are right and consumer and environmental groups are wrong, but in general, I think the positioning of farmers in opposition to environmentalism and consumer demands for transparency, animal welfare, and sustainable production put farmers in an increasingly isolated position. Their superior political organization coupled with the outsized political representation of rural voters can only outrun increased interest in what we eat and where it comes from for so long.

Examples from 2017

#CARGILLGATE: Cargill partners with the Non GMO Project, Ag Twitter explodes.

The freakout on Ag Twitter when the commodity broker Cargill signed an agreement with the Non-GMO Project to certify their non-GMO commodities was significant and dissonant enough that I managed to slough off this year’s writer’s block enough to write something about it:

So when Cargill touted their existing relationship with the Non GMO Project on Twitter, all hell broke loose. Especially on Ag Twitter.

I could see why farmers would be annoyed that Cargill would partner with an organization that routinely throws the average American farm under the bus. On the other hand, I can see why Cargill would partner with a non-GMO certifier that has greater brand equity and might be able to deliver a larger niche price premium than more technocratic industry third party certification services.

What surprised me was the depth of the anger and sense of betrayal. What Cargill was doing was a pretty straightforward business decision aimed at fattening the bottom line, one that might even deliver better bushel prices to farmers selling into that market. As farmers are apt to tell anyone that has suggestions on how they might do farming better, at the end of the day, it’s the bottom line that keeps the lights on. There are a few reasons I think we saw such a highly agitated response to a rational business decision by privately held, profit maximizing firm.

The first and most obvious to me is the sense of betrayal at a firm whom farmers see as a coalition partner. The ag producer community sees itself in a coalition with the big ag input companies (Monsanto, Syngenta, John Deere, etc), the big middlemen (Cargill, ADM, Tyson, etc); and the big food processors (General Mills, Proctor and Gamble, etc) against consumer and environmental groups. The big firms fund a lot of agricultural advocacy and they are lobbying partners on various pieces of legislation relating to GMO labeling, animal welfare standards, environmental protections. The partnership of Cargill with the Non GMO Project violates the shared priorities in this coalition in a fundamental way.

This is all the more striking against the backdrop of nearly complete apathy in the ag producer community to any interest in market concentration or antitrust concerns. While farmers became grievously exorcised about Cargill partnering with the wrong third party certifier of non-biotech crops, concerns about market concentration sapping their bargaining power as price takers in the commodity markets mostly generates yawns outside of press releases and congressional testimony from the head of the National Farmers Union.

Monsanto’s Dicamba Debacle: The Empire Strikes Back

In 2016, Monsanto released a new line of soybeans resistant to the herbicide dicamba ahead of the EPA’s approval of the new formulations of dicamba designed to pair with the soybeans. This did not turn out well. Too many farmers facing another year of trying to deal with glyphosate-resistant to pigweed decided the roll the dice and use older formulations of dicamba with the new soybeans. Those formulations are not approved for use on or near soybeans which are very vulnerable to dicamba. The dicamba can volatilize and drift for miles to other fields and inflict serious crop damage. Which is what happened across tens of thousands of acres of soybeans in Arkansas, Tennessee, and Missouri. This caused serious issues between neighboring farmers, to the point where one farmer shot his neighbor when confronted about damage from drift.

Monsanto put the blame squarely on farmers. And while in each individual case, the farmers were clearly responsible, the overall problem had a foregone certainty to it that made it hard not to expect a little more from Monsanto than finger pointing.

Then in 2017, Monsanto and BASF’s new dicamba formulations were approved for use on soybeans despite misgivings from land-grant university weed scientists who felt they hadn’t been properly tested and could still have drift issues. Which they did – across an estimated 3.1 million acres this time. This time around, Monsanto asserted that the issues were human error again and nothing that couldn’t be solved with more education on proper application. Local weed scientists weren’t so sure. They thought that there were still serious volatility and drift issues. State regulators started looking at banning dicamba. Monsanto and the farming community started pushing back on the researchers. NPR’s Dan Charles filed an extensive report. (In fact, his reporting on the issue has been first-rate.)

“If this were any other product, I feel like it would be just pulled off the market, and we’d be done with it,” Bob Scott, a weed scientist at the University of Arkansas says.

But dicamba, and the crops created to tolerate it, aren’t just any products. There is big money behind them. Monsanto, seed dealers, farmers who are struggling with weed problems — they all have a stake in this technology. The university scientists who are pointing out problems with them are confronting an economic juggernaut.

Monsanto — and farmers who want to use dicamba — have been fighting back. In Arkansas, where state regulators proposed a ban on dicamba during the growing season next year, Monsanto recently sued the regulators, arguing that the ban was based on “unsubstantiated theories regarding product volatility that are contradicted by science.” The company called on regulators to disregard information from Jason Norsworthy, one of the University of Arkansas’ weed researchers, because he had recommended that farmers use a non-dicamba alternative from a rival company. Monsanto also attacked the objectivity of Ford Baldwin, a former university weed scientist who now works as a consultant to farmers and herbicide companies.

“I read it as an attack on all of us, and anybody who dares to [gather] outside data,” Scott says. “And some of my fellow weed scientists read it that way as well.”

Bradley says executives from Monsanto have made repeated calls to his supervisors. “What the exact nature of those calls [was], I’m not real sure,” Bradley says. “But I’m pretty sure it has something to do with not being happy with what I’m saying.”

I contacted three academic deans at the University of Missouri, asking for details about the calls. A university spokesman said they were too busy to respond.

Monsanto’s Partridge says, “We are not attacking Dr. Bradley. We respect him, his position, opinion, and his work. We respect him, and academics in general.”

Bradley says criticism from people in Missouri’s farming community whom he has known for years hits him even harder. “To have somebody say that what [I’m] saying is bad for Missouri agriculture, that’s a hard one to take,” he says. “There’s not a lot of glory in these positions, or major financial incentive. We chose these jobs to help the farmers in our states.”

Academic weed scientists are supportive of farmers through their research and extension work, that’s the mission of ag departments in land-grant universities. They are often funded in part by the big seed and chemical companies. But they also tend to be committed environmentalists. Part of their mission is also advising state regulators the best they can. In this case, those goals and alliances were at cross-purposes in very uncomfortable ways.

Missouri is requiring special training for dicamba applicators above and beyond their general certification. Two weeks ago, a legislative panel in Arkansas gave backing to a ban called for by the State Plant Board. There is legislative pressure in Illinois for a ban as well.

Trouble at the GMA

Meanwhile the coalition of major food processors like Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, General Mills, et. al, with their suppliers, again ADM and Cargill along with ag groups like the Corn Growers Association has been fighting a rearguard battle against consumer demands for transparency and public health advocates demands for nutritional labeling and more nutritious formulations of processed food, mostly reductions in sugar. Some companies are ready to throw in the towel and give consumers what they want. Others have acquired smaller brands that were already meeting those consumer’s needs and don’t see any upside having their parent company pouring millions of dollars into fighting against the corporate missions of the smaller brands they just spent tens, if not hundreds of millions of dollars acquiring.

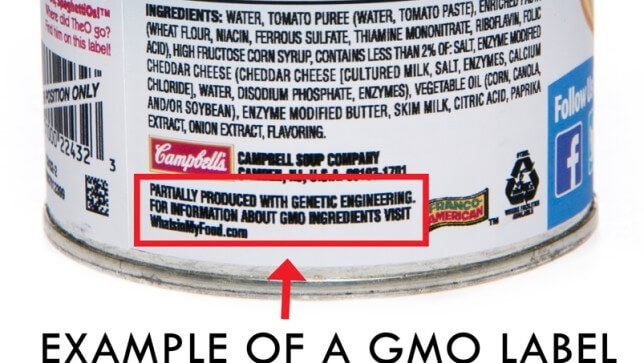

The cracks in the coalition became clear in July of 2017, when Campbell’s announced they were pulling out of the Grocery Manufacturing Association (GMA). Unlike companies which have followed, they were publicly explicit about their reasons. They had opposed the GMA’s role in passing the SAFE Act of 2015 which made provisions for voluntary GMO labeling, but foreclosed a national mandatory label. In 2016, Campbell’s became the first major food company to provide voluntary GMO labeling on their products.

The cracks in the coalition became clear in July of 2017, when Campbell’s announced they were pulling out of the Grocery Manufacturing Association (GMA). Unlike companies which have followed, they were publicly explicit about their reasons. They had opposed the GMA’s role in passing the SAFE Act of 2015 which made provisions for voluntary GMO labeling, but foreclosed a national mandatory label. In 2016, Campbell’s became the first major food company to provide voluntary GMO labeling on their products.

They also plan to comply with the FDA’s new nutrition labeling guidelines new nutrition facts panel by the original July 2018 deadline, even though the deadline has since been pushed back. Meanwhile, the GMA had lobbied against the new guidelines and applauded pushing back the deadline, stating that compliance would be virtually impossible.

Then in October, Politico reported that Nestlé was leaving as well and for similar reasons.

Nestlé has been at odds with the trade association on some of the most high-profile food issues in Washington in recent years. During the Obama administration, Nestlé was among a handful of companies that backed Obama administration effort to mandate added sugars labeling and encourage food companies to cut back on sodium voluntarily — two policies that GMA lobbied against.

Nestlé also helped push GMA to submit split comments on added sugars labeling to the FDA, so the association essentially included the pros and the cons of the policy rather than presenting a unified front opposing the idea. At the time, no one could recall a time when GMA had ever submitted such divergent comments on such a major — and controversial — regulatory issue.

Later in October, Campbell’s announced they were joining the Plant Based Food Association (causing heads to explode across the ag coalition, one imagines).

In December, the GMA was rocked again as Tyson and Unilever left, following defections by Mars and Dean Foods. Then last month, Cargill and Hershey cut ties as well.

Fault lines in the Big Organic house as well

Competing visions and interests aren’t just isolated to conventional producers and the major legacies brands. There is tension between the frenemies of the Non-GMO Project and certified organic. While most organic grocery products have ponied up to the Non-GMO Project, they also fear that the Non-GMO Project is cannibalizing organic sales, as many consumers don’t have a clear idea what the labels represent, they just want a label, any label that signals a “better” product.

Murray’s Chicken, a company based in New York, recently announced that it was now “offering ‘better-for-you’ non-GMO chicken without the organic price tag.” In a Whole Foods Market that I recently visited, the store had posted a sign explaining that organic eggs were out of stock, but that “during this shortage, we have expanded our selection of Non-GMO Project Certified eggs to provide you with high-quality alternatives.”

David Bruce, director of eggs, meat, produce and soy for Organic Valley, a major organic food company, says the non-GMO labels “definitely” are diverting some consumers away from organic food. “We call it trading down,” he says.

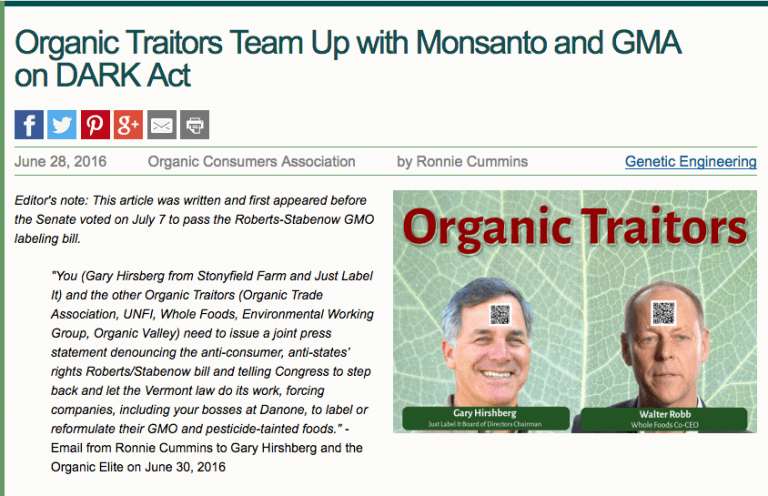

But the biggest break was also due to where the parties came down on the SAFE Act (aka the DARK Act) and mandatory labels.

When the major players in the organic marketing space decided on detente with the GMA and company on mandatory labels and backed the passage of the SAFE Act, the organic grassroots went bananas.

The growing list of Organic Traitors includes the head of Whole Foods Market, Walter Robb; Gary Hirschberg, the CEO of Stonyfield Farm and the pseudo-pro GMO labeling group Just Label It; the Environmental Working Group, represented by Scott Faber, former head lobbyist for the pro-biotech Grocery Manufacturers Association; UNFI, the largest wholesaler of natural and organic foods; and the OTA, led by “natural” brands such as Smuckers and White Wave, and represented by their Board Chair Melissa Hughes from Organic Valley.

These self-selected “Good Food” and “Organic” leaders have been telling Congress behind closed doors—and now publicly—that they and the organic community will accept an industry-crafted DARK Act “compromise”—the Stabenow/Roberts bill— that eliminates mandatory GMO labeling and preempts the Vermont law with a convoluted and deceptive federal regime for QR codes and 1-800 numbers that is completely voluntary, with no firm guidelines for implementation, and no provisions whatsoever for enforcement. Perhaps even more outrageous, the legal definition of “bioengineered” foods under the new DARK Act means that 95 percent of the current GMO-tainted foods on the market, including foods made from Roundup-resistant and BT-spliced corn and soy, would never have to be identified.

Falling out of the good graces of the organic grassroots might be one of the reasons why the avalanche of negative comments on Stonyfield’s recent calamitous “educational” video on GMOs were barely offset by just a handful of supportive comments. The kind of keyboard warriors you’d expect to stick up for Stonyfield and their GMO misinformation campaign don’t consider them a member in good standing of the organic tribe.

This was inevitable

As consumer, especially affluent consumer preferences for food that is, or at least seems, more natural, more authentic, more environmentally friendly and ethical – companies would be inevitably pushed and pulled in new and different directions. Whether that’s Campbell’s embracing transparency, public health goals and joining the Plant Based Foods Association or conventional farmers feeling betrayed Cargill partnering with the Non-GMO Project (but oddly unconcerned about major mergers and further market concentration) or organic activists being consistently disenchanted with organic food as it’s brought to the masses, these coalitions were headed for stormy waters.

Of the predictions I’m making this year, this one is the least specific. It’s barely a prediction actually, more of some friendly advice … watch this space, I don’t have any idea what’s going to happen next only that it will and it will be interesting.

Postscript:

Western Producer reports on Cargill’s continued relationship with the Non-GMO Project while other commodity brokers step into that space as well:

Cargill clarified its position, saying it agrees with the science showing that GMOs are safe. In the same sentence Cargill said it also believes that consumers deserve choices. “Cargill has adopted a “yes and yes” approach – we believe in the science and its benefits, and we understand that both science and consumer values drive decision making.”

The nuanced position didn’t appease the online crowd.

“Sort of like selling ammo to both sides in a civil war,” tweeted Lawrence McLachlan, a farmer from Ontario.

Cargill, despite the criticism, hasn’t backed away from the Non-GMO Project. Cargill states on its website that it has the “broadest portfolio” of non-GM ingredients and a number of them are Non-GMO Project certified.

The Cargill controversy is now old news and possibly forgotten, but not by other players in the food industry.

For other agri-companies the lesson learned is that it’s possible to pull off this sort of duplicity. It’s possible to embrace science and non-science and get away with it. It’s possible to sell into a higher value market, boost the bottom line and withstand the pushback from farmers.

Bunge now has a Non-GMO Project verified vegetable oil, labelled as Whole Harvest. The veggie oil comes from non-GM canola grown in Canada and non-GM soybeans from the U.S. Cibus, a U.S. plant-breeding firm, is now selling a herbicide tolerant variety of canola in Canada that isn’t genetically modified. It hopes to tap into the market for non-GM canola oil, as its canola will be grown for a Bunge crushing plant in Harrowby, Man. Those companies can now sell into the non-GM space, while also claiming to support science and modern agriculture because Cargill has proven that the “yes and yes” strategy can work.

There may be a lesson here for farmers.

Writing angry tweets may feel good but they rarely change corporate behaviour, unless its tens of thousands of tweets from suburban consumers in places like New York, Chicago or Toronto. If farmers really want to get the attention of a grain company, they’ll need a more focused and co-ordinated campaign – perhaps collectively refusing to sell grain to a company that works with the Non-GMO Project.

If growers are unwilling to take collective action on these sorts of issues there is another option – learn from Cargill.

The company’s assessment might be correct.

Marc Brazeau is the editor of Food and Farm Discussion Lab. Follow him on Twitter @eatcookwrite

This article was originally published at Food and Farm Discussion Lab as “2018 Predictions: Fraying Food and Ag Coalitions” and has been republished here with permission.