But the line between satire and sincerity has become blurry on this issue. [December 17], the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), widely considered to be the world’s most prestigious medical journal, published an article entitled Failed Assignments—Rethinking Sex Designations on Birth Certificates, arguing that (in the words of the abstract) “sex designations on birth certificates offer no clinical utility, and they can be harmful for intersex and transgender people.” The resemblance to Titania McGrath’s 2018-era Twitter feed is uncanny. Two of the authors are doctors. The third, Jessica A. Clarke, is a law school professor who seeks to remake our legal system so as to “recognize nonbinary gender identities or eliminate unnecessary legal sex classifications.”

The very idea of “a dichotomous sex-classification system” is dubious, the authors believe. And even if such a system were preserved, they write, it should be based “on self-identification at an older age, rather than on a medical evaluation at birth.” Sex designations on birth certificates, it is argued, “offer no clinical utility; they serve only legal—not medical—goals.”

On social media, where the NEJM article has attracted nearly 6,000 (almost uniformly negative) comments, many readers expressed disbelief that such a piece would appear in the same storied academic journal known historically for definitive, groundbreaking scientific papers on such subjects as general anaesthesia, the discovery of platelets, and the clinical course of AIDS. “I’m a pediatrician,” wrote one Oregon-based doctor. “The growth curves for male and female babies are notably different. Am I to just give up on tracking normal growth and development?”

Sex designations on birth certificates offer no clinical utility, and they can be harmful for intersex and transgender people. Moving such designations below the line of demarcation would not compromise the birth certificate’s public health function but could avoid harm.

— NEJM (@NEJM) December 17, 2020

In apparent anticipation of such responses, the NEJM authors write that “moving [sex] designations below the line of demarcation would not compromise the birth certificate’s public health function but could avoid harm.” The term “line of demarcation” refers to a separator on birth certificates. Information above the line, such as name, sex, and date of birth, generally appears on certified copies of birth certificates and carries legal significance, whereas information below the line consists of medically irrelevant demographic information that typically is included only for purposes of compiling aggregated population statistics. In effect, the authors are urging that a person’s biological sex be downgraded to the same secondary, below-the-line information category that includes, for instance, a child’s race and the marital status of his or her parents.

While such arguments seem inconsistent with common sense (not to mention the daily diagnostic and treatment protocols employed by millions of doctors around the world), the fact that editors at such a prestigious journal as NEJM have chosen to assign credence to these arguments leaves us no choice but to unpack them.

In 2001, a Consensus Study Report titled Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? was approved by the governing board of the National Research Council. Based on input from 16 experts drawn from the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineering, and the Institute of Medicine, all “chosen for their special competences” on the subject matter, the authors of the book-length report concluded as follows:

Being male or female is an important basic human variable that affects health and illness throughout the life span. Differences in health and illness are influenced by individual genetic and physiological constitutions, as well as by an individual’s interaction with environmental and experiential factors. The incidence and severity of diseases vary between the sexes and may be related to differences in exposures, routes of entry and the processing of a foreign agent, and cellular responses. Although in many cases these sex differences can be traced to the direct or indirect effects of hormones associated with reproduction, differences cannot be solely attributed to hormones. Therefore, sex should be considered when designing and analyzing studies in all areas and at all levels of biomedical and health-related research.

This conclusion is hardly controversial. Nor should it be: Until just a few years ago, even most transgender activists didn’t claim that biological sex was a superficial construct that paled in comparison to self-asserted gender identity. Yet the authors still took care to support their conclusions with an abundance of academic citations. The material details the measurably different manner by which the average member of each sex responds to medical therapies and metabolizes nutrients. The report also covered sex differences in overall body size and composition, and the prevalence of obesity, osteoporosis, autoimmune diseases, and cancer. Coronary heart disease—which claims about 650,000 American lives every year, more than double the COVID-19 death toll—is described as a disease “that affects both sexes differently.”

Not only is biological sex a clinically significant factor in medicine, in many cases it is among the most important factors that a patient presents—even putting aside such obvious examples as prostate and uterine cancer, which afflict only males or females respectively.

Lest one dismiss 2001-era research as ancient history, consider another review, published in the Lancet just four months ago under the title Sex and Gender: Modifiers of Health, Disease, and Medicine. “The combination of all genetic and hormonal causes of sex differences [yield] two different biological systems in men and women that translate into differences in disease predisposition, manifestation, and response to treatment,” the authors concluded. “Therefore, sex is an important modifier of physiology and disease via genetic, epigenetic, and hormonal regulations.” In addition to generally affirming the conclusions of the 2001 National Academy of Sciences review described above, the authors detail other afflictions with sexually distinct patterns that have been investigated during the intervening two decades—including Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, influenza, pneumonia, chronic kidney and liver diseases, depression and suicide, and COVID-19. They state plainly that “efforts to bring sex and gender into the mainstream of modern medical research, practice, and education are urgently needed, as the lack of appreciation for sex and gender differences harms both women and men.”

So given this baseline of widely accepted medical knowledge about the important differences between the biologically male and female populations, why did NEJM publish Failed Assignments—Rethinking Sex Designations on Birth Certificates?

To help answer that question, consider the case of another misleading article: Lise Eliot’s appreciative Nature review of The Gendered Brain, a 2019 book by Gina Rippon that inaccurately claimed observed sex differences in the brains of males and females are largely a “myth” that reflects “neurosexist” bigotry. In a published response to Eliot’s credulous take on Rippon’s book, several experts reminded Nature‘s readers that “a variety of neurological and psychiatric conditions demonstrate robust differences between the sexes in their incidence, symptoms, progression and response to treatment… When properly documented and studied, sex and gender differences are the gateway to precision medicine.”

To help answer that question, consider the case of another misleading article: Lise Eliot’s appreciative Nature review of The Gendered Brain, a 2019 book by Gina Rippon that inaccurately claimed observed sex differences in the brains of males and females are largely a “myth” that reflects “neurosexist” bigotry. In a published response to Eliot’s credulous take on Rippon’s book, several experts reminded Nature‘s readers that “a variety of neurological and psychiatric conditions demonstrate robust differences between the sexes in their incidence, symptoms, progression and response to treatment… When properly documented and studied, sex and gender differences are the gateway to precision medicine.”

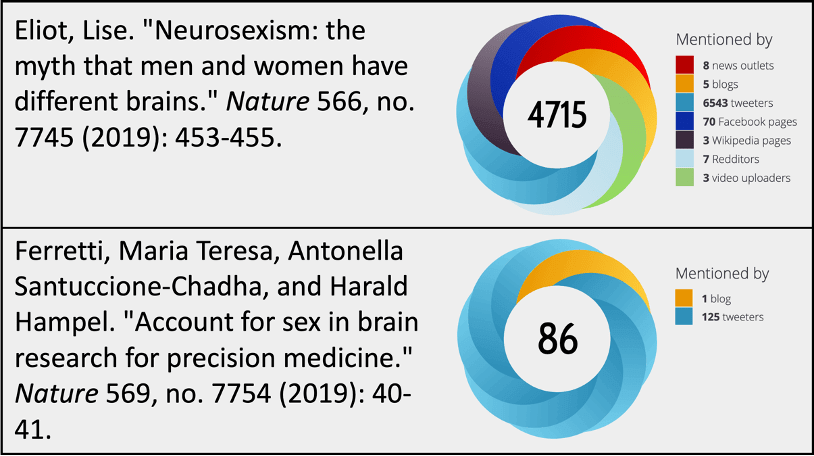

Now consider the different social-media imprints of these two Nature articles, as quantified by the website Altmetric, which tracks the degree to which scientific literature is reported by news outlets, blogs, and social-media users. As the accompanying image shows, the attention paid to Eliot’s positive review of Rippon’s dubious book on “Neurosexism” dwarfed the sober and factual debunking of it by a ratio exceeding 50:1.

Indeed, Nature‘s original “Neurosexism” piece immediately went viral on social media. It showed up in eight news outlets, five blogs, 6,543 tweets, 70 Facebook pages, and received mention on Wikipedia, Reddit, and three video sites. And why wouldn’t it? The idea that there are no sex differences in human neuroanatomy—that we are all blank slates, so to speak, and so any observable variation must be the result of cultural conditioning or sexist bigotry—always plays well in the lay media, as it accords well with the expansive progressive understanding of sexism. Meanwhile, the actual facts, boring as they may be to most social media users—that “a variety of neurological and psychiatric conditions demonstrate robust differences between the sexes in their incidence, symptoms, progression and response to treatment”—barely received any notice whatsoever.

And here we get to what has changed in recent years. Historically, scientific journalists and publishers worked within a professional milieu in which, with few exceptions, the judgments that mattered most were those rendered by other experts. But that’s now changed, thanks to social media. While the editors at such publications as Nature and NEJM may be excellent scientists, they also have the same appetite for praise and acceptance as everyone else. And if social media is telling them that a certain kind of article will mark them as enlightened, surely that will affect their choice of what to publish.

Not to mention, their choice of what to unpublish. On November 17th, Nature Communications published an article titled The Association Between Early Career Informal Mentorship in Academic Collaborations and Junior Author Performance, whose peer-reviewed results challenged the fashionable idea that same-sex mentoring arrangements help younger women. Needless to say, Twitter erupted in fury, leading to a slew of revisions that editors hoped would mollify critics. But that didn’t keep critics at bay. And so this week the article was retracted entirely, with the editors abjectly pledging to now “reflect on our editorial processes and strength[en] our determination in supporting diversity, equity and inclusion in research.” It’s hard not to read this as an admission that the publication will no longer even pretend to ignore ideological fashion in rendering its editorial judgments.

The revisions, and then retraction, were performed under the conceit that Nature Communications editors are simply rigorous scientists responding to “criticisms from readers [that] revolved around the validity of the conclusions in light of the available data, assumptions made and methodology used.” But even if one were to take this claim at face value, it’s clear that such rigor seems to be applied on an ideologically selective basis: The November 17th Nature paper was retracted despite being approved, in its multiple forms, by not one but two peer-review teams—while the NEJM and similarly prestigious publications now publish articles about sex and gender that plainly defy basic biological principles of sexual dimorphism understood even by small children.

It is also unclear how (or if) NEJM editors evaluated the broad claim that registering sex designations on birth certificates “can be harmful for intersex and transgender people”—not to mention the equally unproven argument that “designating sex as male or female on birth certificates” misleads people by falsely “suggest[ing] that sex is simple and binary when, biologically, it is not.”

“Sex is a function of multiple biologic processes with many resultant combinations,” the authors write. “About 1 in 5,000 people have intersex variations. As many as 1 in 100 people exhibit chimerism, mosaicism, or micromosaicism, conditions in which a person’s cells may contain varying sex chromosomes, often unbeknownst to them. The biologic processes responsible for sex are incompletely defined, and there is no universally accepted test for determining sex.”

As a biologist, I understand the terms that are being used here. But as a journalist, I get the sense that the authors’ primary goal is to overwhelm readers with specialized language that suggests an individual’s sex is the output of some complex equation (or, as the authors put it, “a function of multiple biologic processes”). Such language disguises the plain fact that sex is defined functionally based on the type of gamete (sex cell) that forms the basis for an individual’s reproductive anatomy. Males comprise the sex that produces small, motile sex cells (sperm); while females comprise the sex that produces large, sessile sex cells (ova). It doesn’t matter whether any individual can actually, or eventually does, produce gametes. An individual human being’s sex is determined by their primary sex organs, and an individual’s sex is accurately recorded over 99.98 percent of the time using genitals as a proxy for underlying gonad type.

Intersex conditions, whereby a person may have ambiguous genitalia or a mismatch between sex chromosomes and external phenotype, are real but extremely rare. And they do not result in a third sex. Nor do they demonstrate the existence of some mythical sex “spectrum” (notwithstanding several science journalists’ efforts to pretend as much), given that there is no gamete that exists between sperm and ova for one’s anatomy to produce (or be structured to produce). Furthermore, while those with chimerism, mosaicism, or micromosaicism may exhibit variation in sex-chromosome composition on a cell-by-cell basis, every specialist (including those who wrote the NEJM article) knows full well that it is an organism that has a sex, not its constituent cells. The vast majority of people with the above-listed conditions do not exhibit ambiguous sexual characteristics; they are clearly male or female.

The NEJM authors state that sex designations on birth certificates are harmful to people with intersex conditions because the requirement to pick “M” or “F” may serve to increase pressure on parents of intersex infants to pursue surgeries designed to alter a child’s genitals so as to make them appear more typically male or female. While I share the belief that surgeries on intersex infants should be withheld until patients can give proper consent, and that nobody should be pressured into unwanted surgery, birth certificates are not the culprit here. Rather, what needs to be reconsidered is the societal notion that there is only one narrow way for biological males and biological females to look. (Indeed, the authors themselves seem to be exhibiting just such a regressive attitude, as their analysis implicitly rests on the assumption that intersex men and women are not fully male or female, a claim that many intersex people themselves might vigorously and properly reject.)

As for individuals who identify as transgender, their biological sex is typically not in any way ambiguous. A trans person is someone who is male or female, but who self-identifies as someone of the opposite sex—which, of course, they’re free to do, but which does nothing in and of itself to change their underlying biology.

In regard to trans individuals, the NEJM authors write:

Assigning sex at birth also doesn’t capture the diversity of people’s experiences. About 6 in 1,000 people identify as transgender, meaning that their gender identity doesn’t match the sex they were assigned at birth. Others are nonbinary, meaning they don’t exclusively identify as a man or a woman, or gender nonconforming, meaning their behavior or appearance doesn’t align with social expectations for their assigned sex.

While I have no reason to dispute the statistics cited here, it is stunning that this kind of logic would be featured in a scientific journal. “Identity”—including “gender identity”—is a socially constructed phenomenon that says nothing about one’s biological sex. And while it has always been known that some individuals are affected by gender dysphoria, the idea that biology shall be superseded by self-conceived gender identity—not only in the social and legal spheres, but also in some quasi-scientific sense—is a novel claim that would have seemed bizarre to everyone (including trans activists themselves) just a few years ago. Twitter and Tumblr are full of people who insist on the truth of this claim, of course. But they generally do so as activists and moralists—not as scientists.

The NEJM authors claim that trans people are harmed when they’re not allowed to use public spaces according to their self-identified sex, as opposed to their actual biological sex. On this point, the authors aren’t breaking any new ground, but are simply weighing in on an ongoing debate between those who prioritize the desires of trans people (women, in particular), and the hard-won rights of biological women who seek to keep male bodies out of vulnerable female spaces, including locker rooms, prisons, and rape-crisis centers. There is a real good-faith debate to be had about where the rights of one group begin and the rights of the other end, but it has nothing to do with birth certificates, and the authors don’t seem to have any special insight into its resolution. Nor do they grapple substantively with countervailing arguments rooted in biological reality, summarized well by Callie Burt, associate professor of criminology at Georgia State University, in a recently published articled in the journal Feminist Criminology:

Women’s sex-based provisions have been instituted and maintained to mitigate historical and ongoing social disadvantages (e.g., support for women/girls, quotas, and awards and competitions) and to provide female spaces free of the threat of male violence, sexual harassment and objectification to facilitate women’s equal involvement in public life. Some provisions (e.g., female awards and quotas) are designed to overcome social disadvantages rooted in historical exclusion, while other provisions, such as sports and female reproductive control, are sex separated due to biological differences (male physiological advantages and female reproductive burden, respectively) and justified by the individual and social benefits of female social involvement such provisions facilitate (Coleman, 2017). In general, sex-based provisions continue to be crucial to females’ well-being and equal participation in society, facilitating privacy, equal opportunity, and dignity in a world where male people have long been hostile and exclusionary to female people (e.g., Lawford-Smith, 2019a).

What Prof. Burt is describing here are the rights won by generations of women, often at great personal cost, in defiance of patriarchal societies that organized their power hierarchies around the real and timeless biological reality of sexual dimorphism. And it’s been distressing to see how easily many progressive thinkers, including some scientists, have been convinced that this biological reality can be airily dismissed as a mirage.

Even “Titania McGrath” could scarcely have known how quickly such ideological fads would metastasize into medical literature. And it should be a source of shame for the editors of the NEJM that today’s published content now reads as a plagiarized rehash of yesterday’s farce.

Colin Wright is the Managing Editor of Quillette. He holds a PhD in evolutionary biology from the University of California, Santa Barbara. Follow him on Twitter at @SwipeWright

A version of this article was originally posted at Quillette and has been reposted here with permission. Find Quillette on Twitter @Quillette