These are some results from poor righteous risk management.

A righteous risk is a threat of harm to societal well-being that arises when decisions are based solely on widely-shared moral perceptions, social virtues and ethical ideals. This value-based policy approach does not consider facts or data in a consistent manner with certain actors, reinforced by social media tribes, imposing their ideals upon others. Righteous zealots (particularly environmental activists, naturopaths and food puritans) are more intensively forcing their moral dogma upon the policy process. Such value-based regulations are righteous risks that have become a growing threat to entrepreneurs and researchers whose innovations may challenge their traditional ethical norms. In attacking agricultural practices, food choices, energy use, nicotine alternatives and transportation choices, when the righteous feel they have virtue on their side, their reasoning and decision-making become hazardous to others.

This is the introduction to a series on how to manage righteous risks.

Investors struggle today to safely measure financial and economic risks, reduce exposures and identify opportunities. Governments must invest to limit exposures to infrastructure risks. Corporate leaders have to manage trade, market and production risks, often environmental-health risks and, perhaps most importantly, potential regulatory risks. But is anyone managing the threat from righteous risks?

Righteous risks

A righteous risk arises when a decision is taken on the grounds that it is perceived as the right thing, the virtuous answer, what a good leader would do… But the righteous action is not necessarily the best thing to do. Making decisions solely on some ethical dogma, an unwavering virtuous self-appreciation or a fear of some stakeholder moral condemnation can tie policymakers into irrational regulations that do little but harm. The values that guide decision-makers, or the widely expressed social values that decision-makers feel they need to reflect, do not take into account the complexities of policymaking or the compromises that must be made. Politics is a pragmatic profession, but today we seem to have lost the art of Realpolitik, replaced by a “governance by moral aspiration” approach.

Certain cases of “moral reactivism” have had decision-makers assume the virtue position. Be it forest fires, floods and heatwaves, a tragic publicly-viewed murder or a disaster flowing from industrial negligence, leaders who react to public moral outrage with righteous responses may survive a political backlash but risk making bad decisions if they put some moral idealism before pragmatic problem solving. And if issues are too complex or problematic, policymakers can seek the solace of the precautionary principle, claiming to be a caring, concerned leader.

When moral convictions are cleverly used to justify policy actions, who would possibly be concerned about any contradictions or hypocrisy arising from the policies. Leaders who cloak themselves in virtue, from Ottawa to Wellington to Brussels, pretend to be immune to criticism, put economic or social consequences into a larger, moral crusader context and play the progressive card. Those who highlight their failures are moral delinquents, attacking Bambi.

But Bambi is getting pretty smug and their failures are starting to hurt.

The virtue of environmentalism

I had lunch recently with a Brussels insider and we were evaluating the achievements of the von der Leyen Commission. Her tenure was seen as basically a failure (even if we factored out the Timmermans effect). The main weakness was that her policies and postures were more virtue-driven than rational, more ethically-postured aspirations at a time when Europe, faced with pandemics, wars, energy and food inflation and economic crises, needed a more pragmatic Realpolitik approach.

The signature policy of the von der Leyen Commission has been the Green Deal. It was touted as the most important moral and political responsibility of our time to do whatever it takes to combat climate change. There was a war on climate, and thanks to the pontifical architect of this policy, Frans Timmermans, it was also framed as a war against evil: against capitalism and industry.

The word “transition” started to be repeated in any official EU Green Deal speech. When we make a transition, we turn away from the bad and toward the good. The need for an energy transition, mobility transition or a food system transition became synonymous with fighting climate change. But this “transition towards…” strategy, as a righteous crusade, became curious as the Green Deal strategies were presented as virtuous solutions. Renewables, organic food, EVs, non-synthetic chemicals … were promoted within a moral framework, under the virtue of sustainability. Whoever would suggest advancing innovations in carbon capture and storage of fossil fuel emissions instead of more subsidies for renewables had crossed over to the dark side and would soon be ostracised by the community of influencers. When you speak in terms of good v evil in the moral imperative to stop climate change (to right the evils of past generations of unenlightened polluters), the Green Deal becomes a mission of the noble and the virtuous.

The EU Farm2Fork strategy, for example, is built on the perception that organic farming practices are morally superior (not industrial, not chemical-based, more environmentally sustainable). Organic advocates perceive themselves as virtuous (conscious) consumers and, right or wrong, the food companies market into this perception, reinforcing this belief. So who would dare question a major EU policy shift toward organic farming, even if it radically disrupted European food supplies or aggravated global food security? Evil chemical companies lobby for destructive, conventional agricultural practices, pesticides and GMOs while the good small farmers who nourish the land organically are concerned for our well-being. And we are not even talking about vegan sanctimony.

This perception though is myopic and as long as the EU’s food and agriculture strategy favours this righteous approach, the consequences will be more dire for farmers, the environment and consumers. After almost three years of consultation, the European Commission has refused to budge on its pro-organic moral crusade, despite the warnings from its own scientists in the JRC. This perception of a war against evil is a righteous risk that will be very hard to manage if the architects continue to remain doggedly dogmatic. Then again, the vote last week in the European Parliament rejecting the Sustainable Use of Plant Protection Products Regulation (SUR) is a sign that idealistic moral convictions alone might not get the votes in next year’s European elections.

Righteous individuals (zealots) are unable to listen to opposing ideas or to compromise. I once was so disgusted by the self-righteousness of activist campaigns that I came out and admitted that, as a human, I pollute. If we don’t start from that admission, if we assume that the problem is with how others pollute, then we will never be able to achieve any reasonable goal (not of zero pollution but of polluting less). Like most other cults, environmentalism is rife with moral sanctimony.

It is not just the moral rectitude these activists are demanding that is questionable, but also the type of values they are putting forward. Zealots will do whatever it takes to win a campaign (so lying, scaring or misleading the public is acceptable for them). The activists’ commitment to social justice creates a bias against industry, globalisation and capitalism so any potential innovative achievements or system improvements are rejected outright. The values these moral crusaders put forward are framed by their anti-establishment dogma, such as diversity, equity and sustainability. We don’t hear much about honesty, accountability, fair-play or respect for evidence in their campaigns (perhaps these are not Machiavellian values). And if we ever dare suggest they be more transparent on who is funding them, then … well … I paid a price for that heresy.

A redefinition of leadership

This injection of ethical rectitude into policy strategies is redefining Western leadership. Policies are cloaked in values and expressed with hyperbole and categorically. Moral conviction defines today’s bold leaders, standing up for the ideals and beliefs that ought to define our futures and relentlessly fighting against those infidels who dare to oppose “our common values”.

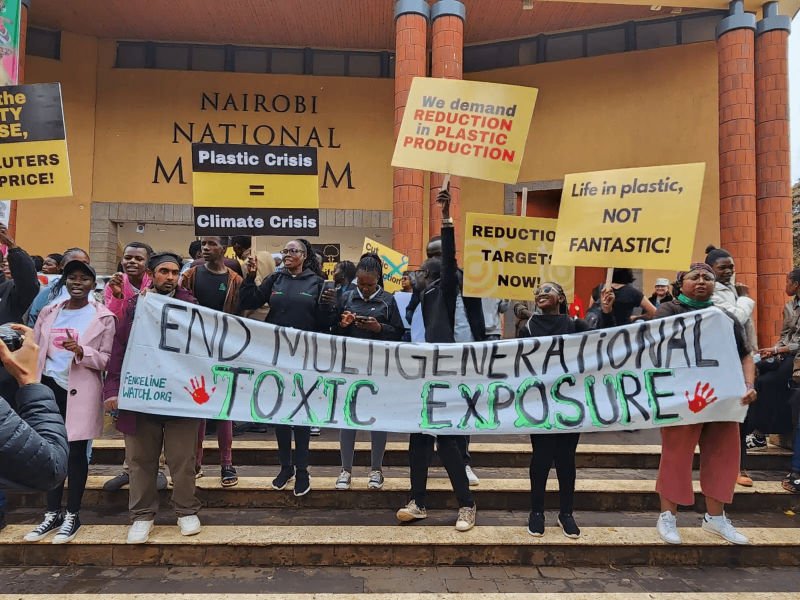

The use of the prefix “zero” is an indicator of a virtue-driven leader prone to moral hyperbole and putting aspiration over achievement. Zero waste, zero emissions, zero plastics, net zero… all of these aspirations are unachievable nonsense that wastes political energy. We should be directing policy toward improving operations and aiming for the best that can be achieved. But the media expects leaders to be about superlatives, absolutes and great moral confrontations on the evils that have been tolerated for too long. Better is not good enough – we must right the wrongs and eradicate the evil to zero.

Leaders used to be able to stand up and make hard decisions, solve problems and inspire populations. This often involved compromises and an embrace of Realpolitik. Leaders would identify themselves via past achievements (battle-hardened generals, business titans, great negotiators…). Today’s virtue leaders aren’t cut from the same cloth, are often clever consensus-builders and need to identify themselves according to public expectations of propriety. They make decisions based on prescribed values rather than insight or intelligence.

Virtue-driven decisions can have serious consequences in the real world. The world is not divided into clear paths between good and evil. Different interest groups have legitimate claims and often hard choices means that the world of rainbows and butterflies may have to wait. But leaders who grasp onto their defining moral character, vision and high self-esteem will likely make bad decisions while claiming, stubbornly, to stand on principle.

Outrage optics

Policymaking has always been about optics. In the last two decades (since the EU White Paper on Governance), European policy has been about engagement, stakeholder dialogue and participation. In recent years it has become a cynical process of “steam control” (to borrow on Tom Wolfe) where moral outrage is controlled via little compromises. But social media has brought high-volume ethical disgust into the policy optics game with very little tolerance for compromise. Social media is an insult arena where angry activists can morally emasculate public leaders who don’t do exactly what they tell them to. Leaders need to harden up. Just because some former Reuters journalist in Kansas calls a regulator names for standing by the scientific evidence on, say, glyphosate, does not mean he or she should abandon basic facts and science to be better judged by this little storm in a teacup.

The zealot influencer is the most dangerous lobbyist in the field, excelling at generating outrage optics within a small tribe of loud activists. They use a sociopathic preacher zeal to push policymakers into a moral quagmire. Support this legislation and you are supporting industry, wilfully spreading cancer on innocent children and destroying the environment. The argument is not about evidence or scientific advice, but on whether you, as a leader, are a good person. Outrage optics campaigns work on the idea that people will forget a policy choice in weeks but will never forget an irresponsible leader in the pocket of evil industry. When this emotional quagmire is too difficult and the moral outrage too insufferable, the precautionary principle is introduced as a mea culpa.

Precaution is a righteous risk. When a policymaker is being stabbed with hot moral pokers, they can reverse the tables and play the caring, concerned card. By declaring precaution, cowardly leaders can not only avoid the outrage optics, they can come across as benevolent regulators with a conscience, wanting nothing more than public safety. This little game buys them time since innovators will have to go back to prove with certainty that something is 100% safe (a near impossible task). By then these civil servants should have been promoted to some other position.

Some people are sickened by the smug pontifications of moral zealots and the costs of precautionary restrictions on their lives. There seems to have been a recent increase in extremist party electoral wins, the rise of inexperienced populists and the rejection of traditional, mainstream political parties. Foul language, racist declarations, lawbreaking and radical solutions are becoming more attractive to voters fed up with their virtue-driven leaders. There are many factors, of course, to explain this rise but I can understand the appeal of someone who tears up the political virtue manual and says things his or her electorate wants to hear (however outrageous) rather than the moralisms some out-of-touch leader feels the public ought to hear.

Developing a righteous risk management strategy

This series will look at case studies where righteous risks were (or were not) managed, the consequences and the lessons learnt. I will break righteous risks down and apply the normal risk management process and consider whether there are idiosyncratic exposures that defy typical responses or a policy trend that needs addressing. One article will look at the policy arena to determine the relationship of righteous risks within a larger regulatory risk management context. Of course we need to follow the money and the rise of new types of philanthropic foundations, led by virtue-seekers, has had an important influence on the rise of value-driven policies. The series will also consider how companies should react? After Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development, will the Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) value hoops be enough to meet the moral approval of the sanctimonious?

Is it wrong to be critical of stronger moral values guiding public officials? Not at all. But when all policies are driven merely by ethical values and unbending zealots; when activists frame every policy debate in simplistic, good v evil poles; when policymakers are inconsistent in their regulatory implementations according to perceived normative interests; and when the public is persuaded to consider capitalism, innovation and entrepreneurship as moral deficiencies; then righteous risks become a threat to rational policies, democracies and the public. I’m afraid that’s where we are today but it is where we go tomorrow that interests me.

David Zaruk is the Firebreak editor, and also writes under the pen-name The Risk Monger. David is a retired professor, environmental-health risk analyst, science communicator, promoter of evidence-based policy and philosophical theorist on activists and the media. Find David on X @Zaruk

A version of this article was originally posted at Risk-Monger and has been reposted here with permission. Any reposting should credit the original author and provide links to both the GLP and the original article.