The most desirable cotton is distinguished by having extra-long staple fibers (Egyptian, Pima) and such cotton commands a price premium. But as the cotton moves around the world, and through the fabric value chain, there is the potential for it to be diluted with, or fraudulently replaced by, lower price and lower quality materials.

Clothing manufacturers like to make quality-related or sourcing claims but the closer an item gets to the retail shelf, the harder it is to certify that the garment is really made from the type of cotton they intended. Until now.

A company based on Long Island, Applied DNA Sciences (ADNAS) (NASDAQ: APDN), has developed ways to identify what is real and what is not in this market. They can use DNA testing to identify the native cotton species and, in turn, verify cotton items. Their methods can tag and test cotton textiles and finished goods to provide traceability to the source, where the cotton was grown and harvested. They employ the sort of sophisticated DNA testing typically used in human forensics — the kind of thing you might see on an episode of CSI.

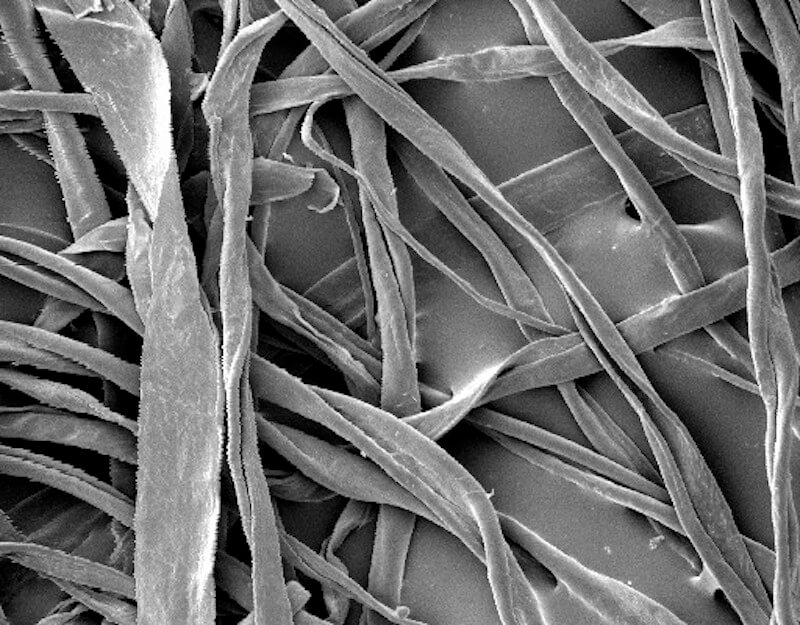

How does this work? Each cotton fiber was originally a living plant cell, so it had the full compliment of cotton genes. By the time the cotton boll matures, the cells are no longer viable and the DNA begins to degrade, something that continues during the many steps of ginning, spinning, weaving, dying etc. Still, enough DNA fragments remain to allow ADNAS to detect important elements of its genetic signature. They can already tell the difference between something like the premium Pima varieties and common upland cotton using a technique called fiberTyping.

Like many crops, cotton has to be adapted to the growing conditions in each region. That means that cotton grown in India, China, Spain, Egypt, or Uzbekistan may have unique and detectable differences in their DNA. Recently, ADNAS partnered with the Agricultural Research Service Genetics Unit of the US Department of Agriculture, who have an extensive collection of cotton germplasm from around the world, to verify multiple types of individual cotton cultivars in order to assist the cotton industry in protecting quality, traceability, and economic investments.

This means that in the near future, a clothing company may be able to make label claims about cotton quality and origins no matter how convoluted the path has been from the farm to the store. In addition to quality issues, responsible clothing manufacturers want to be able to avoid sourcing their cotton from parts of the world where undesirable practices like forced child labor are known to happen. This will also protect the farmers who grow the high quality product. There are many other logical applications of this sort of technology to other commodities such as olive oil, premium wine or the dietary supplement industry.

ADNAS offers another service that it calls “SigNature-T” which can be used to intentionally “tag” cotton or other commodities for aspects of how they were produced — things that go beyond anything specific to the plant’s own genetics. For instance, an on-the-ground certifier could inspect a crop to document the fact that it was grown using sustainable farming practices like no-till and cover cropping.

ADNAS has identified certain unique, botanically derived, DNA tags that can be added to the cotton in tiny amounts at a step like ginning. Later, that DNA signature can be detected to confirm the origin of the cotton and allow the retailer to say the cotton was produced with x,y or z desirable methods. Again, this same approach could be applied to many different types of crops to verify a variety of claims.

Cotton has been a logical place for ADNAS to begin because it represents literally hundreds of millions of tons of product from around the world and they have the capacity to do the tracking for that kind of volume. But the approach could be applied to many different plant-based products which all carry, or have the potential to carry, distinctive “stories” in their DNA. Through the incredible advances in the field of molecular biology, those stories can now be used to encourage and reward “integrity” in the system.

You are welcome to comment here and/or to email me at [email protected]

This article originally appeared in Forbes here and was reposted with permission of the author.

Steve Savage is an agricultural scientist (plant pathology) who has worked for Colorado State University, DuPont (fungicide development), Mycogen (biocontrol development), and for the past 13 years as an independent consultant. His blogging website is Applied Mythology. You can follow him on Twitter @grapedoc.