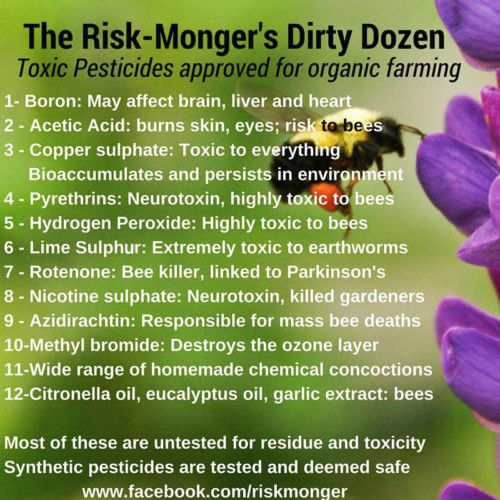

The organic food lobby responded to the attention drawn to their big lie with more wordplay and deception, claiming now that organic food is not grown with any “synthetic” pesticides or that organic farmers don’t use “toxic chemicals”. When confronted with the use of some very hazardous organic pesticides like copper sulphate or neem oil, they claim that farmers are only allowed to use small amounts and only when necessary. In some countries, organic farmers are also permitted to use certain synthetic pesticides (if the organic-approved ones are not efficient). But there are thresholds to maintain to still call their produce “organic”.

To aggravate the situation, each country has its own standards and tolerances for what is needed to fulfil the “organic” certification and are not easily forthcoming on sharing their preconditions (which evolve quite frequently). International organic food lobby groups like IFOAM don’t clearly define acceptable practices, whether it be on pesticides, seeds, fertilisers or growing methods.

So, what does organic mean and to whom?

Traditionalists

From permaculture to biodynamics, a traditional organic farmer starts with soil health as fundamental, seeking approaches to reduce fertilisers and increase biodiversity. The term ‘regenerative agriculture’ was promoted by the Organic Consumers Association, but this term has now been adopted by conventional farmers practising conservation agriculture (no-till farming with complex cover crops terminated with herbicides). While soil health is the main concern for all farmers, many traditional farmers define ‘organic’ solely by doing what benefits the soil (naturally). “Soil is the source of life!”

A few years back, organic purists were outraged that the USDA allowed hydroponic-grown food to be labelled as organic (bioponics). These are not just grown without soil; they tend to consume large volumes of liquid fertilisers and energy. While increasing yields without pesticides, hydroponic farms are also often large, capital-intensive operations. Many of the emerging vertical farming operations tick all of the boxes for sustainable agriculture in urban environments, but they also tick off most organic traditionalists.

Technologists

Perhaps the greatest failure for the organic movement was the missed opportunity to allow several of the new plant breeding techniques for organic seed development. There was open debate in 2015 about the benefits of NPBTs until anti-industry activists in IFOAM, OCA and Corporate Europe Observatory shut down the idea. The radical gardeners in the organic lobby considered this as “GMOs through the back door”, not natural and driven by patents. While I struggle with their definition of a natural seed, this discussion showed how the hardliners see technology merely as biotech (and unwelcome). This failure to allow science to support nature was a fatal blow to organic agriculture’s ability to be competitive and sustainable.

As technology advances in fields like precision farming and robotics, will the traditionalists continue to obstruct solutions that would help organic farmers achieve their goals while making a living? This (younger) part of the movement will have to speak louder if they are ever to secure a future for organic farming.

Agroecologists

Many in the organic lobby have pinned their colours onto the agroecology mast. While there are many definitions and standards for agroecology (including some non-organic techniques), the reactions against large, intensive farming, corporate involvement and the globalisation of the food chain has defined it mainly as a social justice movement. The call for social justice in developing countries includes a plea to promote organic practices among smallholders and subsistence farmers. Given that most poor smallholders are organic by default, the only thing the agroecology/organic movement is doing is giving a small amount of funding and advice without the means to lift peasant farmers out of poverty. Agroecology here is more of a political ideology of agriculture, with many well-known activists like Vandana Shiva claiming it as their own. It adds a political dimension to the radical organic wing (while impoverishing farmers).

Pioneers

There are some third or fourth generation farmers, often driven by market opportunities, who can afford to partially rotate into large-scale organic production, find or innovate on organic methods while developing best practices for the next generation of farming. They are using emerging technologies, combining planting approaches and taking risks. Conventional farmers are looking over the hedge with curiosity. Driven by discovery rather than ideology or labels, these pioneers are the one hope for the future of organic agriculture.

Time for a change

As the term “organic” is merely a marketing tool, carrying no real added value to consumer health or the environment, we need to rethink how food production is considered. There are some organic practices that are beneficial, but there are also conventional technologies and synthetic substances that better improve yields and protect the environment. With the challenges facing agriculture, we need pragmatism and ingenuity, not blind, cultish ideology and fear-driven marketing campaigns. My next column will look at an alternative to this organic/conventional polarity by introducing a concept called “better farming”.

David Zaruk has been an EU risk and science communications specialist since 2000, active in EU policy events from REACH and SCALE to the Pesticides Directive, from Science in Society questions to the use of the Precautionary Principle. Follow him on Twitter @zaruk

A version of this article was originally posted at European Seed and has been reposted here with permission. European Seed can be found on Twitter @EuropeanSeed