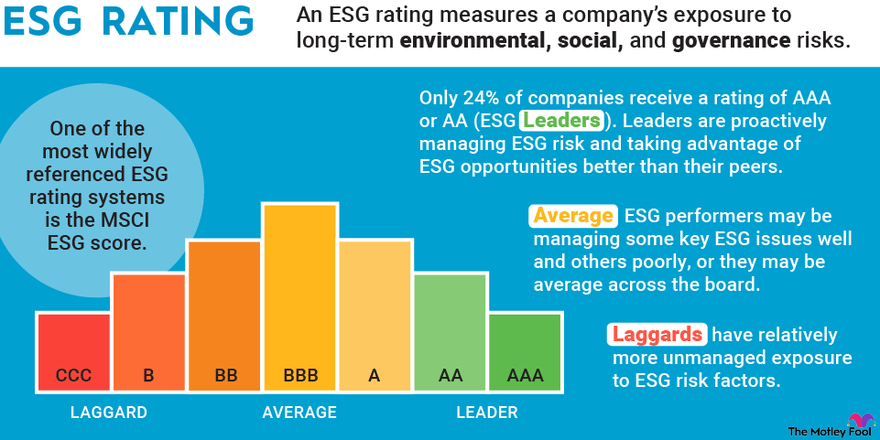

Those hoops have become tighter and, for the food industry, have thus filtered down the value chain to farmers. Food manufacturer ESG scores now depend on how green the farmers can grow the food and feedstock for their downstream processors (everything from the chip to the salad to the sweetener now has to comply with some company’s ESG targets). Since farmers are rarely treated fairly by the food value chain, this worries me. That ESG is an endless process of “improvements” imposed by people with little understanding of agricultural challenges means that the goal of achieving sustainable intensification (and farmer profitability) is getting further from reality. But as long as farmers can meet the targets food corporations and retailers are imposing, corporate stocks will be harvesting profits.

I recently met with a large group of farmers and most shared the same issue: the downstream ESG interference with their farming practises is becoming intolerable. Some examples of how food manufacturers’ ESG demands are harming farmers’ ability to succeed:

- Farmers with contracts to supply food processors are now having their fertiliser and water use audited (with reduction targets in place).

- Clients are starting to request that suppliers adopt regenerative farming practises (regardless of the crop, climate or their particular growing conditions), eliminating other cash crops without compensation.

- Sustainability groups have food waste reduction targets that conflict with how farmers utilise lost yields in the fields.

- Certain pesticides and chemicals, while not banned from the market, are entering onto ESG watch-lists.

The implication here is that farmers who require fewer crop inputs (fertilisers, pesticides, water, modified seeds…) will have more value in the ESG investment point race. So will farmers now have to make decisions not on the basis of what is best for their crop or soil, but on what will make some corporate investor relations director shine at the next general assembly?

The externalising of ESG up the value chain is a cynical move by the food industry to claim credit for the achievements of others. Rather than working on improving their own internal water and waste reductions, companies can claim success on standards they imposed on their suppliers – in this case, farmers. One farmer told me:

Companies are “using their propaganda machine to say to the less educated consumer, ‘Look at what we’re making our growers do.’ They should be using their giant propaganda machine to try to destroy the image that farmers are stupid.”

Where farmers and food processors need to strengthen their trust and cooperation, ESG is driving a wedge between them. Whatever happened to dialogue?

ESG: Bad for the environment, bad for consumers

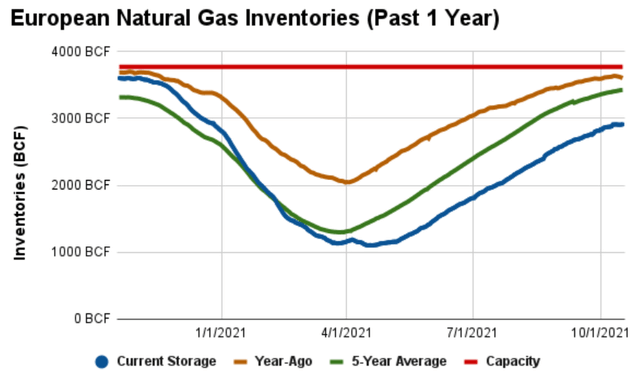

This is not the first time investor obsession with ESG has buggered up global trade, the environment and development. The recent European energy crisis and under-investment in the energy transition has as much to do with random ESG point deductions for companies investing in natural gas projects as with the Russian invasion of Ukraine (natural gas is, after all, a fossil fuel and thus does not tick the right bean-counter box). This juvenile categorisation has also restricted energy projects in developing countries where financing any fossil fuels would have hurt a bank’s ESG ratings (and might have pulled them out of an ETF).

But if an unsophisticated scoring valued natural gas at the same ecological level as coal, this bodes poorly for farmers unwittingly being pulled into the ESG investor points game. At some point, someone in an auditing firm cubicle may be persuaded to value organic food with more ESG points than conventionally-grown. At which point large food corporations, in satirical Dilbertesque fashion, will all pile into demanding to source only organically grown food. What would then happen to US corn yields if, for example, sweeteners would have to be organic and non-GMO? Stupid ESG decisions by naive auditors will not only make it impossible for farmers to supply the food processors; these arbitrary board-room decisions will ultimately affect global food security.

I fear we are getting close to that. Corporate demands for regenerative practises assume a one-size-fits-all approach. While I have been a strong supporter of cover crops and no-till for more than a decade, anyone who has been on a farm will tell you there are different soils, different crops and different climates that make such farming decisions highly selective. Forcing all farmers in a particular supply chain to plant certain covers or take a cash crop out of rotation to meet some ESG goals for that company’s market is hurting the farmer (and the food supply). Worse, for many crops, they will need to invest in new equipment to adapt their practises. Farmers who need to irrigate or apply certain fertilisers or pesticides should look at what is in the best interest for their farm and their crops and not be burdened with having to consider what is in the best interest of some downstream company’s inclusion in some arbitrary ESG ETF. Farmers are rightly frustrated.

We’re trying to produce more with less, not less with more.

Farmers have signed up to the sustainable intensification of agriculture objective (getting higher yields on less land to rewild less productive soils). ESG agriculture is demanding that farmers produce less with more inputs (and more work). This is doomed to failure but the farmers will not be the only ones to suffer. Like the ESG energy debacle, food prices will rise.

The reality is that the impossibility to meet the endlessly tightening ESG standards will lead to rampant cheating (what I called “organish” food) or non-reporting of necessary farming practises. But this “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach will conflict with the ‘G’ in ESG – governance – that demands transparency and integrity.

To be honest, the entire ESG process lacks integrity.

Smallholders have small voices

And what will this fund-driven demand for ESG points do to farmers in developing countries?

This is where I really have to hold my nose as the great and the good down the food chain pontificate their extreme mixture of sustainability and social justice PR. “Fair trade” set the standard for hypocrisy as compliance standards and certification bureaucracy disqualified most smallholders (the ones who needed the support and markets). Thankfully, people with concern for genuine social justice stopped using that hollow marketing trick (although some agroecologist vultures are still feeding off of its rotting carcass).

Sustainable farming has become the new buzzword where Western ideals for ecology are imposed on subsistence farmers in developing countries. Take for example, SIFAV, the Sustainable Initiative on Fruits and Vegetables whose objective is to “drive sustainability within global supply chains, with a focus on reducing the environmental footprint, improving working conditions, wages and incomes, and strengthening due diligence reporting and transparency.” Environmental / Social / Governance. Their mission statement essentially assures companies who commit to this supply chain label that this will be enough to deliver the highly-prized ESG points.

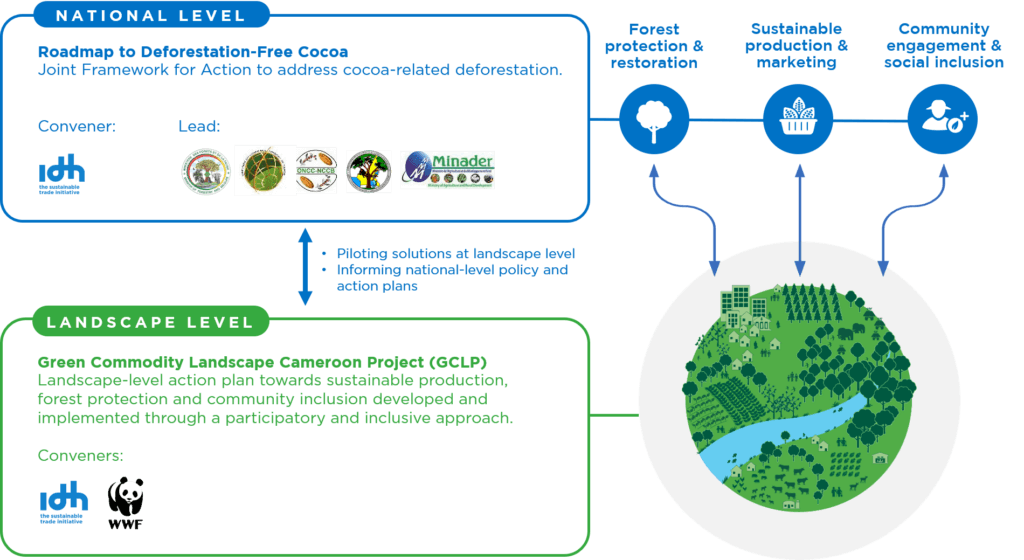

But SIFAV’s sustainability reduction targets will deliver more suffering or exclusion of smallholders in developing countries who will have to make the sacrifices to meet the ESG targets. SIFAV’s steering committee is mostly made up of retail and food processing companies and a few NGOs (well… is WWF still an NGO?). No voice of farmers, agronomists or farming representatives at the table to temper the zeal of their strategic planners. SIFAV is managed by IDH – the Sustainable Trade Initiative. In other words, ESG has become a new, more complex type of fair trade – old wine poured into new bottles, but this time the wine has turned to vinegar by the time it is imposed on the farmers.

Single voice… simple message… coordinated

I recommend that farmers should join together and politely inform their urban, PR-savvy clients that they already follow the best farming practises possible according to their particular conditions and challenges and that their focus on food quality and sustainable yields is more important than some investment fund’s ESG requirements. Farmers have to make it clear that they are equal partners in the food chain, and not some bit player that can easily be replaced if they don’t submit to the investor-driven ESG demands.

What would a baker be without grain? A butcher without livestock? Managers in food processing businesses who think food comes from their factories need to spend some time on the farm. The worst offender, Chipotle, in their Scarecrow campaign, painted the conventional farmers who provide most of their food as grim, soulless and toxic. Farmers should have joined together to boycott supplying such a dreadful organisation.

I have argued before that the food value chain needs to be integrated with a clear single message, coordinated and simply communicated. The organic food industry does just that – it presents itself as a single organism, on message (even if there are many definitions of organic and their idealism is unrealistic). As long as there is opportunism dividing the actors in the conventional food chain, messages will be mixed and trust will be weak. Farmers’ interests have to play an important part of that message – if arbitrary ESG standards make them unable to farm, then retailers and processors will be unable to sell.

Quite frankly, with ESG, the corporate investor relations managers need to suck it up and leave their silly points collection process to reflections on their own company’s internal management achievements. Go into your budgets, buy a wind farm and stop screwing farmers. Farmers deserve respect, not lectures. Farmers deserve support, not sacrifice. They have more important things to do than worry about whether the food manufacturers survive another random round of some ESG Squid Game.

David Zaruk has been an EU risk and science communications specialist since 2000, active in EU policy events from REACH and SCALE to the Pesticides Directive, from Science in Society questions to the use of the Precautionary Principle. Follow him on Twitter @zaruk

A version of this article was originally posted at Risk Monger’s website and has been reposted here with permission.