Members of the Japanese committee that found researcher Haruko Obokata guilty of misconduct have now had their own work called into question.

Obokata rocketed to fame and then infamy beginning in January of 2014 with the publication of two papers in Nature outlining her success at creating stem cells — a vital component of regenerative medicine — via a relatively simple process called STAP (stimulus triggered acquisition of pluripotency). When last I addressed this story in early April, Obokata had been holding her ground. Despite the fact that an investigative panel at RIKEN had found her guilty of misconduct, she insisted that the STAP process was legitimate and that any errors in her work were made in good faith. She was going to appeal the findings.

Now, David Cyranoski, writing for Nature, has an update on the controversy:

On 6 May, the Japanese media reported that the investigative committee decided to deny Obokata’s request for a re-examination. Obokata can no longer appeal the finding through the organization’s appeal system. RIKEN will now begin the process of deciding penalties to Obokata and her co-authors.

That might have been that, but of the six-member investigative committee put together by RIKEN, four have come under fire for irregularities eerily similar to Obokata’s. The first sign that something was amiss came in late April:

On 25 April, the head of the investigation committee, Shunsuke Ishii, resigned from the committee after manipulated images from two of his earlier papers were posted on the Internet. Ishii maintains that neither of the problems amount to fraud, and he posted photos from the original laboratory notebooks to support that point. RIKEN launched a preliminary inquiry into his papers.

More trouble arose for RIKEN on 30 April, when a whistle-blower alleged problems in the images of papers co-authored by two other RIKEN researchers on the committee, Haruhiko Koseki and Yoichi Shinkai. RIKEN launched a preliminary investigation into the allegations that same day. Satoru Kagaya, a RIKEN spokesman, says that the whistle-blower, whose name RIKEN will not reveal, alleges that four papers from Koseki, published between 2003 and 2011, and one paper by Shinkai, published in 2005, contain data that were manipulated in one or two spots.

Meanwhile, also on 30 April, a journalist from the daily newspaper Asahi Shimbun notified Tokyo Medical and Dental University of allegations regarding Tetsuya Taga, the university’s vice president and another one of the RIKEN panel investigators. Two papers on neural stem cells co-authored by Taga, from 2004 and 2005, each had two illustrations that, the journalist said, appeared to be manipulations.

Obokata had first come under scrutiny when members of the science blogging community pointed out that some of the images in her high-profile STAP papers from January appeared to have been manipulated. So what separates Obokata’s manipulations and those of the people investigating her? According to Obokata’s lawyer, nothing; she made have made errors, but there was no misconduct. Not everyone agrees:

Masahiro Kami, a cancer researcher at the University of Tokyo who also researches the communication of biomedical science, sees a difference between the types of problems that surfaced in Ishii’s papers and those found in Obokata’s. He says that, for example, Obokata’s inability to produce data to explain some problems in her papers could be a factor in judging the papers differently. “To decide whether it is fraud, one has to look more comprehensively,” he says.

The RIKEN spokesman says that the allegations against the committee members will not affect the committee’s decision concerning Obokata’s appeal, expected by the end of this month.

The debacle raises fascinating questions about the culture of science and in particular research in Japan. Cyranoski’s article ends with University of Tokyo cancer researcher Masahiro Kami praising RIKEN’s quick and thorough response, saying it could put RIKEN at the forefront of efforts to clean up the scientific literature.

I’m not entirely convinced. From my outside perspective, this seems like an increasingly problematic investigation. How are we to trust in RIKEN’s ability to self-regulate if a majority of the people on its investigative committee can be accused of behavior similar to the person they are sitting in judgment of? Wouldn’t RIKEN have a conflict of interest in this situation?

The brouhaha has made waves in the media, first with Obokata’s apparent success and then her dramatic fall from grace. It would seem that the last thing committee members would want now to is to back-track and put everyone who investigated Obokata under the same level of scrutiny.

Which brings me to a fascinating piece on Nippon.com about RIKEN’s public relations campaign for Haruko Obokata and how it backfired. Takeda Tōru writes:

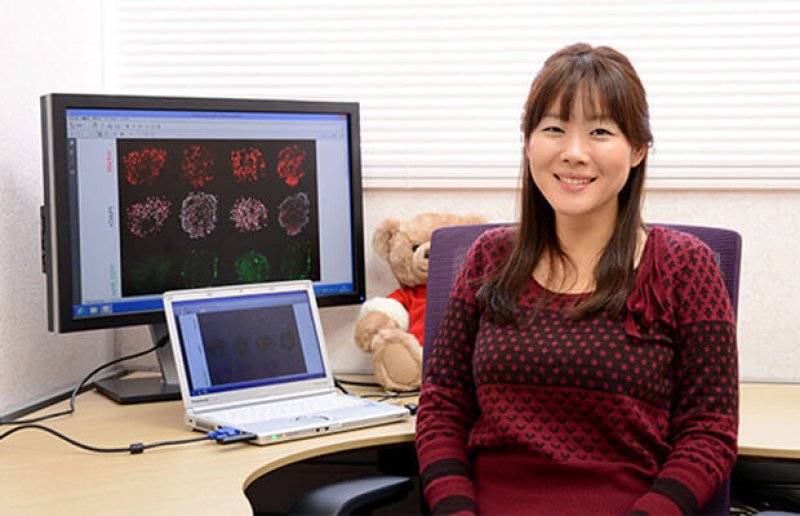

When Obokata hit the scene with this announcement, the Japanese media lavished coverage on her laboratory, which featured pink and yellow walls decorated with Moomin goods and stickers that she said she loved to collect. She wore a traditional kappōgi apron given to her by her grandmother rather than a lab coat when she was conducting research. And in her spare time—not that she had much, as she worked for more than 12 hours every day, including on weekends—she looked after a pet turtle that she kept in the laboratory. Numerous media sources repeated these stories.

Indeed, in following this story I was often struck by how personality-driven the coverage seemed. Always at the forefront was Obokata, a perfect poster-child for breakthrough science; the science itself often got pushed to the side. This was no accident, apparently.

It later emerged that all of the appealing background provided for Obokata’s research announcement had been carefully constructed beforehand by senior researchers at Riken and the institution’s public relations team.

It worked too well.

After the January 28 press conference to the point where she could no longer go out in public. Unable to talk to Obokata directly, the tabloid weeklies began producing a mishmash of facts and gossip about her boyfriends and relationships.

Interest in Obokata spread among Internet users, who started checking through her doctoral thesis. They discovered that photographs she used in the Nature papers appeared in an entirely different context in her thesis and that she had copied large sections of material without properly attributing the sources. As doubts were raised about falsification of some other photos in the Nature papers, Riken was forced to launch an investigation.

Which brings us, after several months of increasingly clouded accusations and investigations, to the current situation. STAP stem cells still have not been reliably reproduced in any other lab, Haruko Obokata remains defiant, and the glare of the spotlight has brought the public to question the very people who were tasked with investigating Obokata in the first place. It’s all very dramatic, and a very compelling story. And this is, I think, where Tōru sounds a pitch-perfect note of caution:

The unfolding events now seem to be packaged with more focus on the Riken-versus-Obokata story than on scientific fact. Society has no interest in the truth outside the framework of a personality-based story—or, to put it the other way around, nothing else matters so long as there is a compelling story to tell.

Kenrick Vezina is Gene-ius Editor for the Genetic Literacy Project and a freelance science writer, educator, and naturalist based in the Greater Boston area.

Sources:

- “Accusations pile up amid Japan’s stem-cell controversy,” David Cyranoski | Nature

- “The Great STAP Cell CommotionHow Riken Lost Control of Its PR Offensive,” Takeda Tōru | Nippon.com

Read the other Gene-ius posts on the STAP stem cell controversy:

- “Embattled STAP stem cell researcher: I’m not guilty of miscounduct, technique works,” Kenrick Vezina | Genetic Literacy Project

- “Breakthrough STAP stem cell researchers officially guilty of misconduct,” Kenrick Vezina | Genetic Literacy Project

- “Promise of “easy” stem cells comes under investigation,” Kenrick Vezina | Genetic Literacy Project

Additional Resources:

- “Riken stands behind STAP paper probe,” Tomoko Otake | The Japan Times

- “Researcher won’t retract STAP cell paper,” Kyodo News