India has become the world’s largest organic textile exporter following its rapid move from conventionally-grown saved seeds—which were often underproductive—to GMO Bt insect resistant seeds. (Bacillus Thuringiensis is a soil-dwelling bacterium, harmless to humans, that naturally repels many predators and was engineered into the seed; organic farmers spray their crops with Bt while GMO farmers use no spraying as the natural bacterium has been engineered into the plant.)

Introduced in India in 2002, Bt cotton is now grown by more than 90% of that country’s cotton farmers, and turned India from an importer to the world’s largest exporter of cotton. Socio-economic surveys confirm that Bt cotton continues to deliver significant and multiple agronomic, economic, environmental and welfare benefits to Indian farmers and society including an 80%+ drop off in the use of certain insecticides and a dramatic increase in yields, as much as double in some cases.

At odds with scientists and independent global agricultural groups, anti-GMO groups have aggressively promoted their belief that the Bt cotton in India has been a ‘failed experiment.‘ They claim there has been a sharp increase in farmer suicides and that farmers are being ‘denied’ the opportunity to save and replant their seeds…memes repeated in this December 30 article in the Washington Post by Esha Chhabra, “The dirty secret about your clothes.” The report focused mainly on the appalling conditions in India’s cotton-based textile industry and links them to GMO cotton. The GLP offers some summary excerpts from the Washington Post story followed by an analysis.

Excerpts of Chhabra’s report:

[D]yeing is only one part of the manufacturing process. The clothing material itself, namely cotton, poses a separate threat to farmers. Only a decade ago, Indian farmers planted 80 percent of their crop using seeds saved from cotton grown the year before. But the advent of genetically modified (GMO) seeds drove that tradition out of the market. Farmers were originally attracted to the GMO varieties because they produced bigger yields than natural seeds, and were supposed to be weed-resistant.But once they stopped replanting natural cotton seeds, those varieties disappeared from the local agriculture. Today, more than 90 percent of Indian cotton comes from GMO seeds, which has forced farmers into a cycle of debt, according to Vandana Shiva, an agricultural activist. GMO seeds are expensive, and because GMO plants don’t produce fertile seeds of their own, new seeds have to be bought each season. Furthermore, pesticides are used on the GMO cotton fields.

Since 2004, however, a cooperative that now numbers more than 35,000 organic-cotton and fair-trade Indian farmers is forgoing chemicals, and building a new seed bank of non-GMO cotton seeds.

Analysis by GLP:

Far from the critical eye of their science editors, an article appeared recently in the Washington Post business section that spread misinformation about organic and GMOs. In “The dirty secret about your clothes” author Esha Chhabra spins a tale that serves to raise fear and doubt in something as simple as a cheap cotton tee-shirt.

The majority of the article is about the dyeing process in factories. It even begins with an anecdote from a factory worker who claims to have suffered from an unnamed disease causing his skin. Factories in India are a concern for the environment especially, and factory workers have a long history of health concerns globally. Chhabra mentions the Noyyal River and how it has become severely polluted. Unfortunately she leaves out the major cause, which is a lack of enforcement of the regulations that would stop these factories from polluting in the first place. According to The Hindu:

It’s a problem that won’t be solved simply by creating more factories with different methods, and certainly has nothing to do with the farming methods of cotton.

Chhabra writes that Indian farmers are suffering from GMOs, specifically genetically engineered (GE) cotton. She states that GMOs eliminated seed saving and that the GMOs were supposed to be weed resistant.

Currently the only GE cotton available in India is insect resistant, herbicide tolerant GE cotton (assuming that is what she meant by “weed resistant”) has yet to be approved there. Research has shown that from 2002 to 2008, GE cotton in India has “caused a 24% increase in cotton yield per acre through reduced pest damage and a 50% gain in cotton profit among smallholders” leading to a significant increase in the living standards of these farmers and a significant reduction in their exposure to insecticides.

As for seed saving, her claim could not be further from the truth. The introduction of Indian cotton varieties with foreign traits dates back hundreds of years. The East Indian Trading Company began importing American cotton seed in the 1840s, more than 150 yearsb before the first GE cotton varieties came to market. According to India’s Central Institute for Cotton Research:

There are four cultivated species of cotton viz. Gossypium arboreum, G.herbaceum, G.hirsutum and G.barbadense. The first two species are diploid (2n=26) and are native to old world… The last two species are tetraploid (2n=52) and are also referred to as New World Cottons… G.hirsutum is the predominant species which alone contributes about 90% to the global production… Perhaps, India is the only country in the world where all the four cultivated species are grown on commercial scale.

Only the G.hirsutum variety has had the gene for insect resistance added to it via genetic engineering.

Andrew Porterfield, writing for the Genetic Literacy Project, explains why it is that only activists (rather than farmers) complain about not saving seed. It is really more about an anti-corporation agenda rather than worrying about the farmers:

The first generation from F1 (aka, the second generation) will have half of the traits you want. Keep breeding like this, and you stand greater chances of losing the traits you want, and growing traits you don’t.

Using saved seeds are less reliable. Many times the traits you must value are just lost, or the risk of less than high quality crops is high. Farmers are hard nosed business people; they can’t afford to risk weak harvests; they are willing to pay a premium for seeds that grow true.

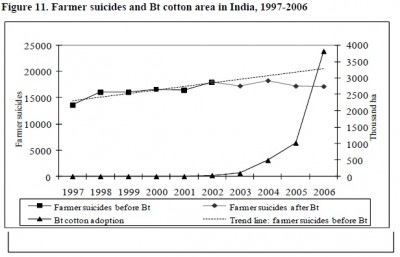

Chhabra’s misinformation may have come from the only source in the article she mentions in regards to GMOs, Vandana Shiva. “Vandana Shiva (born 1952) is an anti-globalization, anti-corporate, deep ecology and radical eco-feminist activist whose campaigns focus primarily on food and agriculture socio-economic issues and an opposition to GMOs, free trade and intellectual property rights. “ Shiva told Chhabra that GMOs have forced farmers into a cycle of debt and that GMOs do not produce fertile seeds of their own. Such GMOs are actually a myth and the overall rate of Indian farmer suicides (often due to debt) is actually at about the same level it was well before the introduction of GMOs.

Shiva should be more than aware of these facts because prior to the introduction of GMOs into India, she made many of the same arguments about “non-GMO” hybrids. A 1998 interview with Shiva finds her using those same arguments in regard to seeds she seems to want Indian farmers to go back to now.

Writing for Fashion Hedge, Theyarina explains why “organic” does not tell the consumer anything positive or negative about a cotton tee-shirt:

Summarizing, the use of pesticides is allowed, natural and synthetic (in moderate quantities). However, as a reminder, just because something is organic in nature, it doesn’t mean that is harmless…. It has also been found that some natural pesticides can be even more dangerous that synthetic ones…. there is nothing about it that helps saving water, as that is not one of the factors to be considered organic on any of the standards I have looked into. Organic cotton is just as bad as regular cotton in this aspect…

Let us also not forget what happened when a Bloomberg journalist looked into labor practices on organic cotton farms “where Victoria’s Secret usually buys up the entire fair trade and organic-certified cotton crop to make the lingerie it sells in the West. There, the magazine found children of 12 and 13, laboring in the fields on pain of being whipped with switches by their bosses the cotton farmers”.

This is what happens when one does not use modern technology to farm, you are left with the age old practice of child labor.

Yes, chemicals being used in factories in India are probably causing a problem for the environment and their workers. But to link those concerns to GMOs and an agricultural system that is showing many signs of helping India is just dishonest. The Washington Post’s science editors have done a great job over the years, perhaps the business editors should have run this by them.