While critical information about abortion is omitted at many of the crisis pregnancy centers, misinformation is apparently readily dispensed. One popular mantra is that abortion causes breast cancer. It’s a claim likely to scare the daylights out of young, vulnerable women seeking help. But a deep-dive into studies published in the top medical journals shows it is untrue — but findings of those investigations tend not to be shared.

Perpetuating an alternate fact

In 2014, NARAL Pro-Choice sponsored a project by then-recent high-school graduate Dania Flores. She visited 43 crisis pregnancy centers in California, focusing on facilities in lower-income areas, and kept a diary of what she was told.

Flores told the LA Times that workers at all 43 clinics informed her that abortions cause breast cancer. “You’re 16 and they’re telling you you’re going to get breast cancer,” Flores said. “You don’t want to get breast cancer, so you don’t do it.”

Cancer fear is used as a deterrent. Flores’ work and that of others contributed to the passage of the 2015 law that the Supreme Court just overturned.

A look back at the medical literature reveals where the idea that abortion causes breast cancer may have arisen. It also shows data — yes, facts — that some pregnancy crisis clinic workers conveniently omit when counseling patients.

Origin of the idea

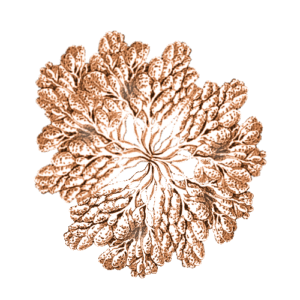

Abortion as a risk factor for breast cancer does make a certain biological sense. During pregnancy, breast cells first divide rapidly and then differentiate (specialize) to elaborate the mammary glands. Breast cancer risk increases slightly during the early proliferative phase, but falls as the cells specialize. Observations in the 17th century that breast cancer is more prevalent among nuns lead to the idea that pregnancy is actually protective.

A study from 1980, “Susceptibility of the mammary gland to carcinogenesis. II. Pregnancy interruption as a risk factor in tumor incidence,” may have ignited the abortion-breast cancer link. In it, rats exposed to a carcinogen while pregnant or lactating were less likely to develop breast cancer than rats whose pregnancies were interrupted.

If an abortion, spontaneous or otherwise, halts the pregnancy, perhaps the hormone-guided proliferating cells are more likely to become cancerous because cancer-causing mutations happen as DNA replication errors when cells divide. But epidemiological evidence argues against this theoretical risk, and is more powerful than the emotional rhetoric that hurls slurs rather than presenting data. Consider “Study proves abortion causes breast cancer, so where’s the headlines?” from a 2013 article in Catholic Online: “Abortion isn’t safe, no matter what the militant left tells you. Their propaganda may be slick and refined, their tactics are honed, but they’re still wrong. These are the facts: life begins at conception, every abortion kills a baby (hardly the definition of safe), and mothers increase the risk to their life with each procedure.”

The Danish study

The lack of a link is crystal clear in the results of a 1997 study reported in The New England Journal of Medicine, “Induced abortion and the risk of breast cancer.” The peer-reviewed NEJM is hardly my idea of slick propaganda.

Tapping data from the National Registry of Induced Abortions and the Danish Cancer Registry, researchers assessed the histories of all 1,529,512 women born in Denmark between 1935 and 1978. Of the women, 280,965 had at least one abortion, and of these, 1,338 women developed breast cancer later. But of the 1,248,547 women who didn’t have an abortion, 8,908 developed breast cancer – a slightly higher rate than the women who’d had abortions. Adjusting for various factors makes the risk about equal. The investigators concluded:

The risk of breast cancer among women with a history of induced abortion was no different from that among women without such a history, nor did we find that the number of induced abortions increases the risk of breast cancer.

A trend emerged, however, when considering the risk of breast cancer by week of gestation when the pregnancy ended (age of the woman didn’t matter). Although the risk of breast cancer was actually lower for women who’d had abortions at seven weeks or earlier, for women who had abortions later than 12 weeks, the risk increased above that of pregnant women not having abortions. (Later abortions are more likely to be done because of a severe fetal anomaly.) But how many women faced this increased risk? Only 37, out of the 1,338 women who developed breast cancer of the 280,965 women who had abortions. Do the math.

“The fact that such an increase did not affect the overall result clearly indicates that it is based on small numbers and therefore requires cautious interpretation,” the researchers wrote.

In case these stats weren’t convincing, the NEJM ran an editorial, “Abortion, Breast Cancer, and Epidemiology,” by Patricia Hartge, ScD, from the National Cancer Institute. “In short, a woman need not worry about the risk of breast cancer when facing the difficult decision of whether to terminate a pregnancy,” she wrote. And subsequent large studies in other countries confirmed the findings of no link. Planned Parenthood describes these studies in detail here.

Focus on small, flawed investigations

Focus on small, flawed investigations

The pregnancy crisis clinics dishing out misinformation, if they present data at all, rely on case-control studies obscured by small samples, recall bias, and women intentionally not divulging abortion history because the procedure was illegal when performed. For example, this meta analysis that purported to find a link combined results of several small studies that the Danish researchers argue are biased and the statistics flawed. Yet the Catholic Online article refers to these small studies, giving the appearance of scientific analysis.

Sometimes the deadly warnings from crisis centers don’t even bother with data. For example, buses in Philadelphia proclaimed a message from “Christ’s Bride Ministries” warning that ‘women who choose abortion suffer more and deadlier breast cancer.” That’s from 1999 – two years after the NEJM study appeared.

Investigations that go forward and track data, rather than relying on women recalling an upsetting event, tell a different story.

“Induced and Spontaneous Abortion and Incidence of Breast Cancer Among Young Women: A Prospective Cohort Study,” published in JAMA Internal Medicine, countered the findings of the oft-cited small retrospective studies. And the title of this 2004 article in The Lancet reveals it’s power: “Breast cancer and abortion: collaborative reanalysis of data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 83,000 women with breast cancer from 16 countries.” They found no link. The paper explains the widespread and fundamental bias of retrospective studies: women with breast cancer are more closely followed medically and therefore more likely to report having had an abortion.

(Caveat: Large numbers are more convincing, but breast cancer risk is also a personal matter. Genetics counts. I breastfed 3 children, which lowers my risk, but my mother had breast cancer and so do I. Any risk assessment must include family history and perhaps genetic testing.)

The official word: ACOG

It’s easy to find position statements that summarize and verify the medical literature, such as The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee Opinion, Induced Abortion and Breast Cancer Risk from August 2003 and reaffirmed several times with new data, including in 2018.

Because this statement is based on analysis of the peer-reviewed medical literature and dissects the sources of bias in smaller studies, it should be the gold standard for delivering information on the non-association of abortion and breast cancer. Yet Planned Parenthood offers abundant examples of attempts to present the abortion-breast cancer link as truth. Still.

The NEJM paper on the 1.5 million women clearly showing a lack of a link between abortion and breast cancer has been known now for 21 years. That study tracked an entire nation of women and was published in the most prominent medical journal.

So I can only conclude that the cherry-picking of flawed studies, or not providing valid scientific data at all when counseling women against abortion or not providing information on how to get one, isn’t an honest misunderstanding of or lack of awareness of the findings of the 1997 study. It is instead much more likely a deliberate attempt to mislead women to promote a religion-fueled, anti-abortion agenda.

Ricki Lewis is the GLP’s senior contributing writer focusing on gene therapy and gene editing. She has a PhD in genetics and is a genetic counselor, science writer and author of The Forever Fix: Gene Therapy and the Boy Who Saved It, the only popular book about gene therapy. BIO. Follow her at her website or Twitter @rickilewis.