From gene drives to designer babies, the promise and the peril of genomic technology is increasingly hitting the headlines. But how is the non-scientific public, unversed in the complexities of modern molecular biology, to make sense of this deluge of information — or, indeed, to sift the scientific facts from the pseudo-scientific fictions? Or rather, how can science educators best communicate to a general audience about a genetic revolution that will have profound effects on both humanity and the world at large — and do this in an accessible and engaging way?

One tried and tested method is that employed by Charles Darwin over a century and a half ago in his 1859 classic, On the Origin of Species. To explain his theory of natural selection to a religiously minded Victorian public, Darwin began with a simple and familiar example — that of the selective breeding of domesticated plants and animals. Focusing on the then-popular hobby of pigeon-rearing, Darwin showed how the ever-increasing variety of ‘fancy’ birds had all been derived from a single shared ancestor (in this case, the common rock pigeon). This ‘artificial selection’, as Darwin termed it, was of course analogous to natural selection, the process — as the Origin so eloquently explains — by which “endless [life-]forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved”.

From the origin of all species, then, we can return to the extinction of the specific one noted above. This tragic death was that of the last surviving aurochs, the species of giant wild cattle that, for nearly two million years, had roamed across much of Eurasia and North Africa. And, as with pigeons and evolution in the mid-1800s, aurochs provide an easily graspable example of many of the concepts of early 21st century genetics.

We can begin by noting that the aurochs’ range — both in time and space — overlapped extensively with another lineage that is coming increasingly under the genetic spotlight; that of our own. From Homo erectus (the first hominin to leave Africa, c. 2mya) to Neanderthals and Denisovans, to modern H. sapiens, humanity’s long relationship with the aurochs is almost as impressive as these animals were themselves.

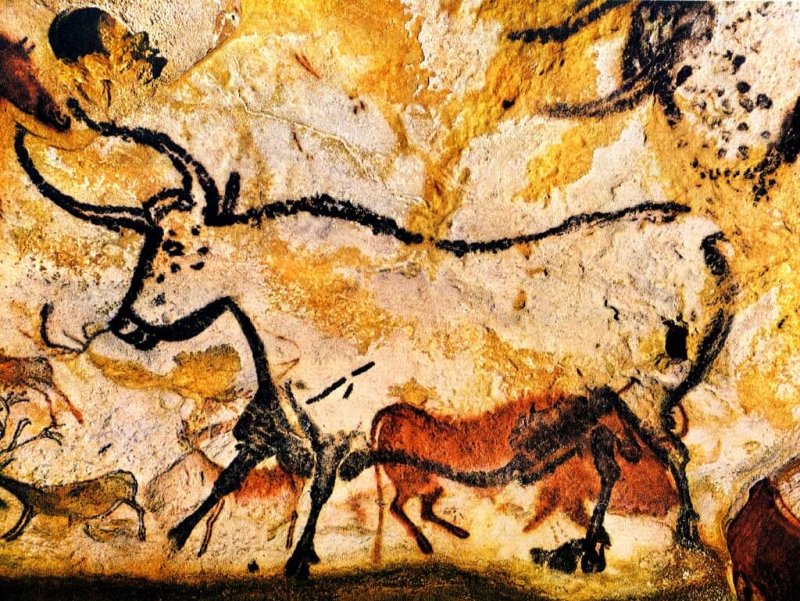

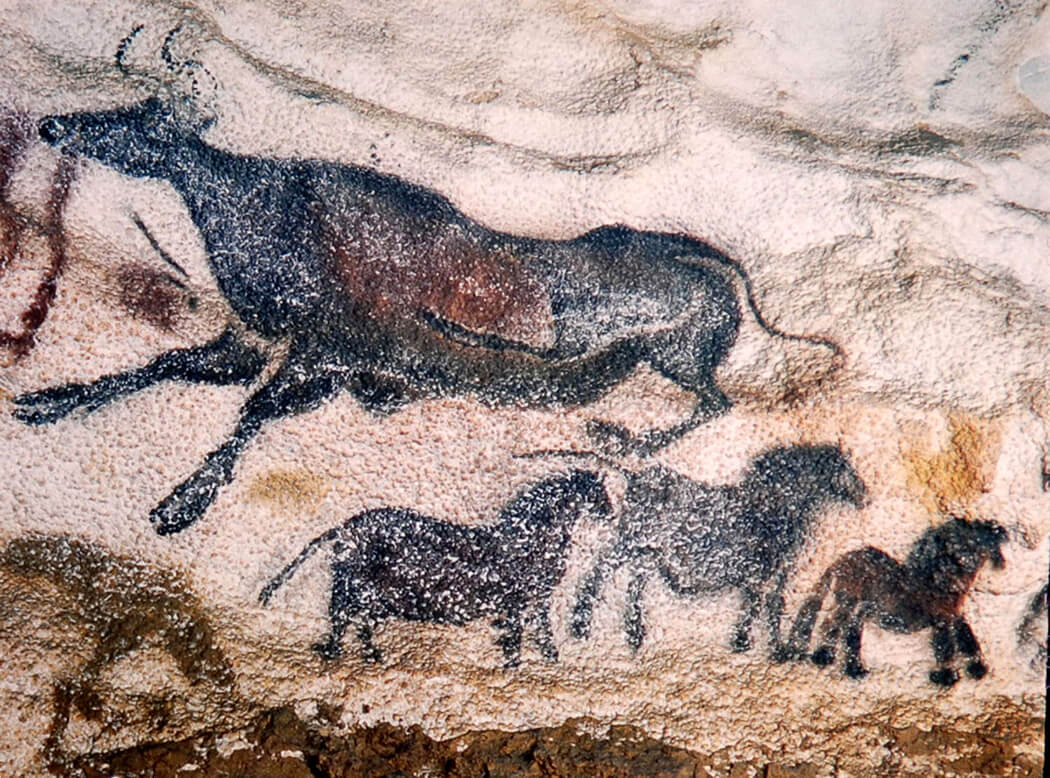

In some of the oldest human creative displays yet known, Paleolithic artists adorned their caves with stylised paintings of these huge creatures, or else permanently etched their images onto stone. Millennia later, the aurochs’ size, speed and strength was recounted with awe by Julius Caesar during his conquest of Gaul in the century before the Christian era. By this time, these animals were already well-established in Eurasian folklore, with the founding myth of Europe symbolised by the Cretan princess Europa and Zeus, her lover, in the form of an aurochs. Ancient travelers’ and writers’ mix of fact and fiction — such as the Greek geographer Strabo’s breathless account of aurochs as “wild bulls of a carnivorous nature” — further cemented these animal’s legendary status in history.

By the late middle ages, however, after thousands of years of ever-increasing human pressure, the last of these ‘wild bulls’ were to be found only in the remote woodlands of Central Europe. By the 1500s, their numbers had dwindled to a single herd in a single forest — the royal hunting reserve of Jaktorówski, south-west of the Polish capital, Warsaw — until, in the early 17th century, the aurochs bloodline was finally erased.

So much for the cultural history — what of the relevance of aurochs to popular understanding of modern molecular biology? The first point here is that, like Strabo’s embellished account of carnivorous cows, it is an exaggeration to claim that the aurochs’ genetic lineage became extinct in 1627. In fact, the aurochs’ genes still live on, in one of the most common and familiar animals on the planet — modern domestic cows.

Genetic and archaeological evidence indicates that aurochs are the direct ancestors of the two major taxa of modern cattle — the humped zebu cows of South Asia and the humpless taurine of the Near East, now best known in Europe and the Americas as beef and dairy stock. This domestication process, beginning between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago, has progressively modified the original gigantic and aggressive aurochs into the smaller, more passive cattle that we see today.

Like Darwin’s fancy pigeons, therefore, modern domestic cattle vividly illustrate the concept of artificial selection. Indeed, in the case of cows, this is literally true, with a millennia-old visual record of how these animals have changed over time — from modern digital photographs and 18th century stock-breeders’ oil-paintings, to the images in medieval drawings and on Bronze Age ceramics, to the lifelike depictions daubed on the walls of prehistoric caves. And even if the story stopped there, it would still be a compelling account of species’ malleability — of how incremental human selection has moulded the wild ancestral aurochs into today’s hugely varied cattle breeds, from the monstrously muscular Belgian Blue, say, to the massively milk-producing Holstein Friesian. But there is a further tale waiting to be told, one with both a happier ending and an exciting new beginning.

As part of the wider rewilding movement, conservationists are even now ‘back-breeding’ from modern cattle varieties that still exhibit aurochs traits (such as shape and behavior) into a single aurochs-like lineage. The eventual aim is to re-create — as far as possible — the ancestral species, and thereby reintroduce a giant herbivore whose grazing will help restore lost biodiversity to the expanding grasslands of Europe.

Controversially, such back-breeding has already been attempted in the past, with today’s notoriously aggressive Heck cattle the direct result of a Nazi-era breeding scheme aimed at recreating the supposed primeval ‘Ayran’ aurochs. Ignorant of genetics, however, these cattle were selected solely on their outward appearance and behavior (or observed phenotype) from breeds such as the Spanish fighting bull. By contrast, today’s revival programs — motivated by a much more laudable cause — are selecting for actual aurochs genes by matching modern cows’ genomes with that sequenced from a 6000-year-old aurochs fossil. Through a combination of conventional breeding, artificial insemination techniques and genetic testing, therefore, cattle whose phenotypes and genotypes increasingly match that of the ancestral aurochs are being raised and released.

Furthermore, other ambitious projects aim to go even further by tackling head-on the fact that some key traits/genes may no longer be found in living cattle breeds. To this end, using gene editing techniques such as CRISPR-Cas9, they hope to synthetically engineer these lost genes — again using the fossil aurochs’ genome as a baseline comparison — to be pasted into existing cattle breeding lines. If successful, this will potentially see the closest thing to a ‘real’ aurochs once more roaming its old Eurasian stomping grounds.

This, in turn, raises a whole host of intriguing questions. For example, would such animals really be ‘authentic’ aurochs? Or should such resurrected aurochs, created from a pre-existing genetic blueprint, still be considered as ‘unnatural’ genetically modified organisms (or GMOs)? And if so, what of the massively modified modern cattle breeds that are currently considered ‘natural’?

Be that as it may, the aurochs’ tale already provides a compelling educational tool — one that allows us to talk bull about genetics, but in an inspiring and informative way.

Patrick Whittle has a PhD in philosophy and is a freelance writer with a particular interest in the social and political implications of modern biological science. Follow him on his website patrickmichaelwhittle.com