GMO field trials banned

In January 2020, a signed petition was sent to several Ministers and Italian representatives in Bruxelles by a group of Italian Researchers who had developed genetically modified (GMO) plants and were requesting the removal of the ban on field trials, that has been enforced on such plants in Italy for nearly 20 years.

The ban applies to both plants that were developed through genetic transfer (GMO) and plants developed with the more recent Genome Editing (GE) technology. It is expected that the latter kind will go through a simplified commercialization approval process, but the road is still long and very uncertain, so much so that Europe has postponed discussions on the topic until April 2021 [1]. It must be noted that controlled field trials remain indispensable for the evaluation of these plants’ virtues and of environmental safety factors, following the EU directive 2001/18 [2].

The European Union continues approving import notices of new GMO products from overseas, this following another directive 2003/1829 [3]; all the while Member States persist with dishonorable hypocrisy of not approving cultivation [4], resulting in enormous economic losses for farmers. Unable to withstand the competition posed by GMO corn with higher yield and better quality, corn growers in the Northern Italian region known as Padania are forced to reduce the size of their own corn fields.

GMO and GE technologies are complementary and indispensable for the rapid constitution of new plant varieties and, thus, must be safeguarded and protected [5]. As certain patents begin to expire, the US continues to develop new plant GMO varieties, some of which are approved for cultivation with a simple notice to be sent to the appropriate authorities, inasmuch as they are already considered GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) [6].

The request to remove the ban

We have requested the removal of the field trials ban on a number of state-funded GMO plants of traditional Italian agriculture varieties, totaling more than 40 individual types, all developed in Italian laboratories. Many of these have been awaiting approval for over 20 years now and no multinationals hold patent rights over them, rendering them available for use by our farmers. These crops were modified to improve their resistance to biotic (fungi, bacteria, viruses) and abiotic stresses; to improve yield and quality. Several Italian institutions have developed new transgenic, cisgenic and RNAi plants that are ready to be transferred to the field, which are important crops for Italian agriculture—in particular wheat, olive, grape, peach and strawberry.

We, therefore, explicitly request that the Italian government put an end to the cunning and rather hypocritical deception enacted thus far, which prevents the Ministry of Environment from authorizing field trials, inasmuch as both the Ministries of Agriculture and the Environment have still not approved trial protocols, and the regions have still not identified trial sites. Such duties were supposed to be performed as far back as in 2007. As a consequence of this, the Italian farming community was deprived of knowledge about the potential risks and benefits of this technology and new products it could produce.

This is the reason why, in the meantime, we also invite business associations to express their positions in a clear and direct manner. Their verbal approval has been expressed on multiple occasions, but in practice, they have provided no support, manifesting instead an anti-scientific attitude and fear of being exposed on the approval of this technology. Alongside politicians, they have constantly abused the phrase “technological innovation,” without ever considering that innovation is achieved through research, through researchers’ dedication, and through adequate human resource and financial investments.

Tackling new emergencies

Nature and human activity perpetually generate new phenomena: the coronavirus, unfolding climate change, and indiscriminate demographic growth are some of the most recent and evident of such phenomena, and which should not have caught us unprepared to provide remedies to the risks they generate. To the contrary, instead of intensifying research to prevent or swiftly combat such risks with new technologies, in some sectors, we are witnessing a rather slow and chaotic scientific progression, burdened by ideological and ethical motivations, and often baseless fears.

The rapid development of disease-resistant plants, such as those that could be obtained through modern biotechnology, is no longer a luxury, but rather an urgent necessity, caused in large part by globalization. The ease and extreme speed with which parasites spread undisturbed increases the necessity for efficient sanitary defenses, which meanwhile grow scarcer.

Biotechnologies are adjunct instruments, often times quicker in responding to farmers’ pressing calls for the development of more sustainable and consumer-friendly production chains, including organic ones. At the same time, their use makes it possible to rescue those typical local varieties, which are at risk of extinction, and which it is our duty to protect to preserve traditions. In fact, Italy in particular has not only delegated the manufacture of biotech products to private institutions — while simultaneously importing them in massive quantities from abroad — but it has also outsourced research, with consequential great losses of know-how and funding from EU programs.

With the arrival of technologies such as Genome Editing and Gene Silencing [[7], [8]], research has timidly picked up again in the biotech sector with the modest enthusiasm of young researchers’, who are, however, forced to pay the cost of almost 20 years of semi-activity, on top of the difficulties and disappointments they are bound to face shortly as they attempt to overcome the insurmountable obstacles of performing banned field trials of their products, especially woody plants [[9], [10]], which are difficult to adapt to artificially confined spaces.

Public should know the benefits of technology

Citizens have the right to know about and observe with their own eyes the real benefits of technology as they are realized in appropriate field trials designed to improve our agricultural production chains.

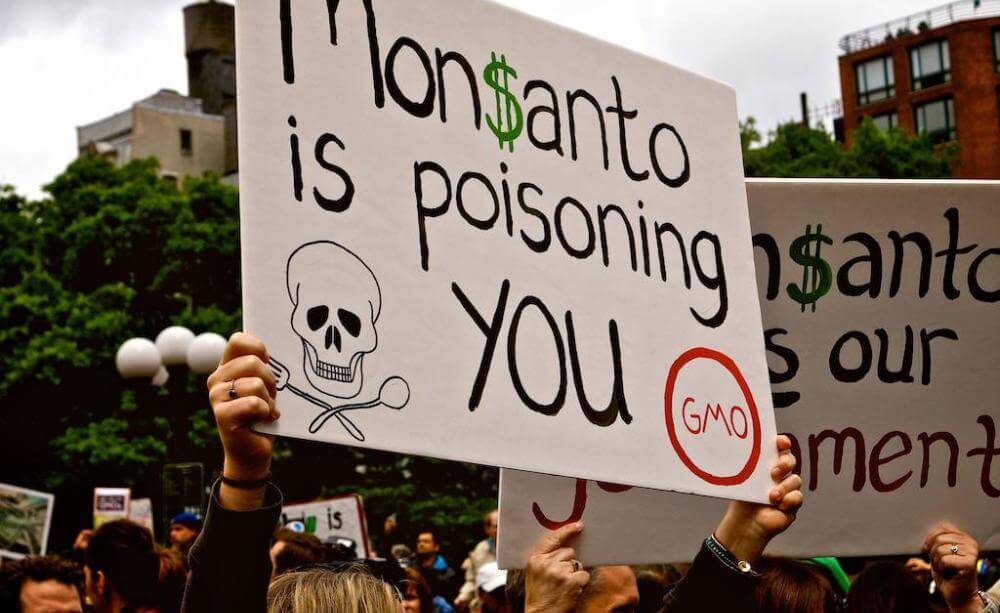

Confusion reigns among citizens today, because they are not provided with sincere and competent explanations of why these technologies are so important and indispensable [11]. This historic moment is defined by an erroneous conviction that everything natural is good; that biotech is the opposite of organic, and that it threatens the biodiversity of plant species. Such false proclamations are predominantly rooted in commercial interests, and they provoke a sense of aversion among consumers to improved production methods and both private and public biotech research. It’s possible that only a food shortage, regrettable as that would be, could communicate the importance of research to the consumer.

Citizens should know that GMO technology has not been a failure in agriculture, as critics would have them believe, based on a small number of commercialized products embodying inferior expectations compared to those once projected. If anything, this is the result of years of anti-GMO activism that has blocked public research — which is by definition accessible and open to all. While the anti-GMO objective may have been to block multinationals, the result has been their strengthening and their increased control over the production of various basic foods consumed globally (corn, soy, rice).

On the other side, policymakers must ensure compliance with the time frames dictated by the regulations and make the final approval decision based on the results of risk-benefit assessments obtained on a scientific basis, instead of public consent, now shaped by anti-GMO movements and by the organic agriculture lobby.

Although it is a matter of fact that genetic innovations obtained through biotechnology are not the only solution in the fight against misery, hunger, malnutrition, and environmental degradation, they can still make a considerable contribution. It is reckless and irresponsible to block them for ideological reasons. This is even more true in regards to Italian researchers, who are denied their right to announce the results of their research; true in regard to farmers, who do not have access to innovations that can ensure greater sustainability for their production systems; as well as to consumers, who are not being correctly informed about the potential food security impact of these technologies.

Italian and EU scientists need strong support to carry their research programs from the laboratory to the field and show growers and consumers the benefits that plant biotechnology can bring to agriculture.

The European Union is launching a new program based on the agriculture ‘green deal,’ but with an unclear position on the important role of plant biotechnologies in improving the sustainability, security and safety of European agriculture. This behavior is no longer bearable for the future of agriculture and the well-being of EU citizens.

References

-

EC Study on new genomic techniques (2019). https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/gmo/modern_biotech/new-genomic-techniques_en

-

EC (2001): https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32001L0018

-

EC (2003): https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32003R1829

-

Giovanni T., 2016. European incoherence on GMO cultivation versus importation. Nature Biotechnology, correspondence, 34.

-

Limera C., Sabbadini S., Sweet J.B., Mezzetti B. (2017). New biotechnological tools for the genetic improvement of major woody fruit species. Frontiers in Plant Science, 8:1418. DOI: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01418

-

Federation of American Scientists (2011). U.S. Regulation of Genetically Modified Crops. In case Srudies in Agriculture Biosecurity: https://fas.org/biosecurity/education/dualuse-agriculture/2.-agricultural-biotechnology/us-regulation-of-genetically-engineered-crops.html

-

Arpaia, S., Christiaens O., Giddings K., Jones H., Mezzetti B., Moronta-Barrios F., Perry J.N., Sweet J.B., Taning C.N.T., Smagghe G., Dietz-Pfeilstetter A. (2020). Biosafety of GM Crop Plants Expressing dsRNA: Data Requirements and EU Regulatory Considerations. Frontiers in Plant Sciences, 24 June 2020: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00940

-

Mezzetti B., Smagghe G., Arpaia, S., Christiaens O., Dietz-Pfeilstetter A., Jones H, Kostov K., Sabbadini S., Opsahl-Sorteberg H.-G., Ventura V., Taning C.N.T., Sweet J. (2020). RNAi: What is its position in agriculture? Journal of Pest Science, in Press. DOI: 10.1007/s10340-020-01238-2

-

Rugini E., Cristofori V., Silvestri C. (2016). Genetic improvement of olive (Olea europaea L.) by conventional and in vitro biotechnology methods. Biotechnology Advances, 34, 5:687-696. DOI: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.03.004

-

Rugini E., Bashir M.A., Cristofori V., Ruggiero B., Silvestri C. (2019). Genetic engineering in fruit trees: A review of results, applications and regulations. Pak J Agri Sci, 57:1. DOI: 10.21162/PAKJAS/20.8361

-

Frewer L.J. (2017). Consumer acceptance and rejection of emerging agrifood technologies and their applications. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 44:683–704. URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10.1093/erae/jbx007

Eddo Rugini is the Vice President of the National Academy of Olive and Oil and a former university professor.

Bruno Mezzetti is a full professor of Arboriculture at the Department of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Sciences at Marche Polytechnic University.

A version of this article was originally posted at the European Scientist website and has been reposted here with permission. The European Scientist can be found on Twitter @EuropeScientist