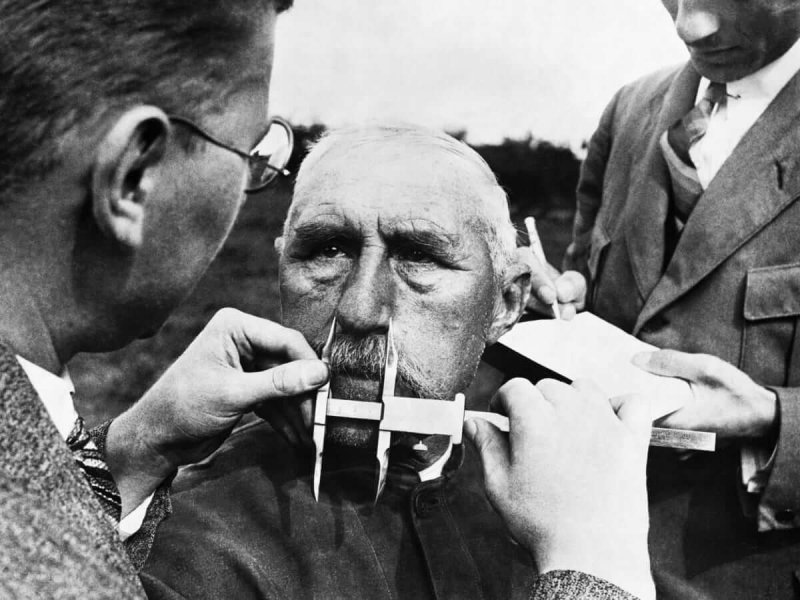

The scientific racism and eugenic delusions that led to the Holocaust are widely eschewed by members of human genetics and genomics communities today. Yet the Holocaust’s long shadow is still evident in public anxiety about our growing ability to control human genes’ expression and transmission.

Today, the focus of this anxiety is on the suite of new molecular tools for gene editing that promises to revitalize the enterprise of human gene therapy. Since the first demonstration that these tools can be used to modify genetic mechanisms in human cells more precisely and efficiently than older forms of gene transfer, global organizations charged with their oversight have produced a deluge of reports and statements proposing ethical guidelines for these tools’ use.

Most of these reports concentrate on immediate research ethics questions raised by the development of any new biomedical innovation: questions about physical risk, informed consent, and fair distribution of research benefits and burdens. But behind those deliberations, the memory of the Holocaust surfaces more fundamental ethical questions about where this research leads and the worry that we could repeat the mistake of creating genetic hierarchies from social prejudices and try again to remake our species against the backdrop of a fundamentally unjust vision of human health.