Presumably, most victims would eagerly forego such benefits if they were able to free themselves of their plight. But when victimhood yields benefits, it incentivizes people to signal their victimhood to others or to exaggerate or even fake victimhood entirely. This is especially true in contexts that involve alleged psychic harms, and where appeals are made to third-parties, with the claimed damage often being invisible, unverifiable, and based exclusively on self-reports. Such circumstances allow unscrupulous people to take advantage of the kindness and sympathy of others by co-opting victim status for personal gain. And so, people do.

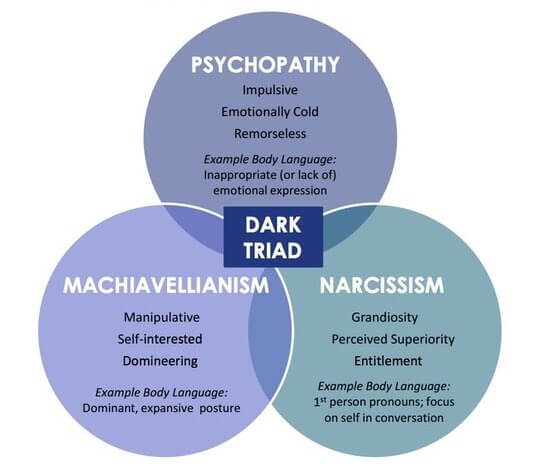

Newly published research indicates that people who more frequently signal their victimhood (whether real, exaggerated, or false) are more likely to lie and cheat for material gain and denigrate others as a means to get ahead. Victimhood signaling is associated with numerous morally undesirable personality traits, such as narcissism, Machiavellianism (willingness to manipulate and exploit others for self-benefit), a sense of entitlement, and lower honesty and humility.

Scholars from the Immorality Lab at the University of British Columbia created a victim-signaling scale that measures how frequently people tell others of the disadvantages, challenges, and misfortunes they suffer. Those who scored higher on this victim-signaling scale were found to be more likely to virtue-signal—to outwardly display signs of virtuous moral character—while simultaneously placing less importance on their own moral identity. In other words, victim signalers were more interested in looking morally good but less interested in being morally good than those who less frequently signal their victimhood.

In one study, participants who scored higher on virtuous victim signaling (the combination of victim signaling and virtue signaling) were, on average, more likely to lie and cheat in a coin-flip task in order to earn a bonus payment. In another study, participants were asked to imagine a scenario involving a colleague (with whom they were in competition) in which “something felt off,” even though the colleague behaved in a genial manner. Highly virtuous victim signalers were more likely to interpret this ambiguous behavior as discriminatory, and to make accusations about mistreatment from the colleague that were never described in the scenario.

In several of these studies, the researchers controlled for the internalization of morally virtuous traits (i.e., actually prioritizing virtue) and demographic variables that might be associated with increased vulnerability to true victimhood. The persistence of statistically significant effects suggests that there may be a personality type that—independent of one’s actual experience of real victimhood or internalization of real virtue—drives individuals to signal virtuous victimhood as a means to extract resources from others.

Consistent with this theory, other recent work indicates that victimhood, or the enduring feeling that the self is a victim, may be a stable personality trait. This personality trait is characterized by a need for others to acknowledge and empathize with one’s victimhood, feelings of moral superiority, and a lack of empathy for others’ suffering. This personality trait was found to be relatively stable across time and relationship contexts, and was associated with higher perceived severity of received offenses, holding grudges, vengefulness, entitlement to behave immorally, rumination, distrust, neuroticism, and attribution of negative qualities to others.

Together, these findings suggest that claims of victimhood may be caused not only by objective states of suffering, but also by the characteristics of the people making claims of victimhood. While we may not be able to control such traits in others, it is useful to examine some of the environmental factors that incentivize the expression of grievances.

In general, people reward victimhood signaling. For example, one study found that participants reported greater willingness to donate to a GoFundMe page for a young woman in need of college tuition when she also mentioned her difficult upbringing, as compared to a control case in which no extra details of past suffering were provided. In many cases, such a result is morally desirable: We want people to help those who have suffered and who are in greater need. However, when it is known that people can attain benefits by projecting certain biographical information, opportunists may be incentivized to exaggerate or falsely signal their own troubles. Just as people may fake competence to attain status and benefits (e.g., by doping in sports, or using one’s smartphone during pub trivia), and fake morality to attain a good reputation (e.g., by behaving better in public contexts than in private situations), they may fake victimhood to get undeserved sympathy and compensation.

It’s also important to remember that many claims of victimhood are made to strangers online, especially through social media or fundraising sites. This can increase the reach and effectiveness of insincere claims because they are directed toward strangers who have no basis for investigating (or even entertaining) suspicions of fake victimhood, except on pain of appearing callous.

When a person knowingly wrongs someone in his or her family, circle of friends, community, or professional orbit, they often are willing to make amends, and so victims can often appeal directly to transgressors for recompense. Even if a transgressor has little remorse, nearby others (such as friends and family) aware of the harm are often willing to provide sympathy and assistance. Third-party appeals to strangers, on the other hand, are perhaps especially prone to falsehood, because the soliciting party is appealing to individuals who don’t know their circumstances or character. This certainly doesn’t mean that all (or even most) appeals of this nature are fake—only that this will be the preferred strategy of those whose claims have been rejected (or would likely be rejected) by those who have the most information.

Nearly all people experience disadvantage or mistreatment at some point in their life. Many quietly and humbly work through these challenges on their own or with the help of close friends and family. Only a minority will turn every slight into an opportunity to seek sympathy, status, and redress from strangers. If eventually discovered, they can suffer catastrophic reputational damage, or even go to jail. But in the short term, at least, this group can receive more benefits, with less effort, than the former.

None of this means there are no genuine victims or that we should not care for and provide assistance to victims when we can. On the contrary, one reason it is worth reflecting on the system of incentives we create is precisely that there are genuine victims: Habitual, false victim signalers deplete available resources for genuine victims, dupe trusting others into misallocating their resources, and can initiate a dysfunctional cycle of competitive victimhood within society more broadly. For example, research has shown that people ramp up their own status as victims of discrimination when they are accused of discriminating against others or even when they are merely characterized as being relatively advantaged.

This phenomenon may help explain why it is common for people to believe that they are getting the short end of the stick in many situations. For example, in a nationally representative poll of Americans, roughly 65 percent of adults expressed at least moderate agreement with the proposition that the system works against people like them. And roughly 55 percent of respondents at least moderately agreed with the proposition that they rarely get what they deserve in life. Most people seem to think that the status quo is generally unfair to them. And the habits of perceiving oneself as a victim, and victimhood signaling to others, are mostly unrelated to political ideology. As with so many sources of intergroup conflict, this is not a “them” problem, but a people problem.

Historically, our ancestors may have been better able to discern habitual or false victim signalers from those in true need. We lived in smaller communities where we tended to know what was happening, and to whom—and so those who deceived others were at higher risk of getting caught.

In modern, affluent societies, by contrast, people can signal their difficult-to-verify suffering to thousands or more strangers online. Although genuine victims may benefit in such environments (because they can spread awareness of their plight, and solicit support, on a large scale), manipulative individuals inevitably will use the same mass-broadcast tools to extract resources and possibly even initiate a cycle of competitive victimhood that infects everyone. Those who most vociferously declare their victimhood to others may often be villains instead.

Cory Clark is a social psychologist at University of Pennsylvania. Follow her on Twitter @ImHardcory

A version of this article was originally posted at Quillette and has been reposted here with permission. Quillette can be found on Twitter @Quillette