As in the past, the controversy over abortion pits the “pro-choice” view, favoring the autonomy and privacy of women, against the “pro-life” view, insisting that human life should be protected at any stage of development. The script is essentially unchanged, but the influential actors are different. The Supreme Court now has a decidedly conservative bend, making it likely that the justices will reinterpret the law as it was laid down in decisions like Roe v. Wade, Planned Parenthood v. Danforth, and Planned Parenthood v. Casey. Collectively, those three decisions only allow states to restrict abortion rights after a fetus becomes “viable,” the point at which it can survive outside the mother’s uterus. With current medical care and technology, that fetal age is between 22 and 26 weeks.

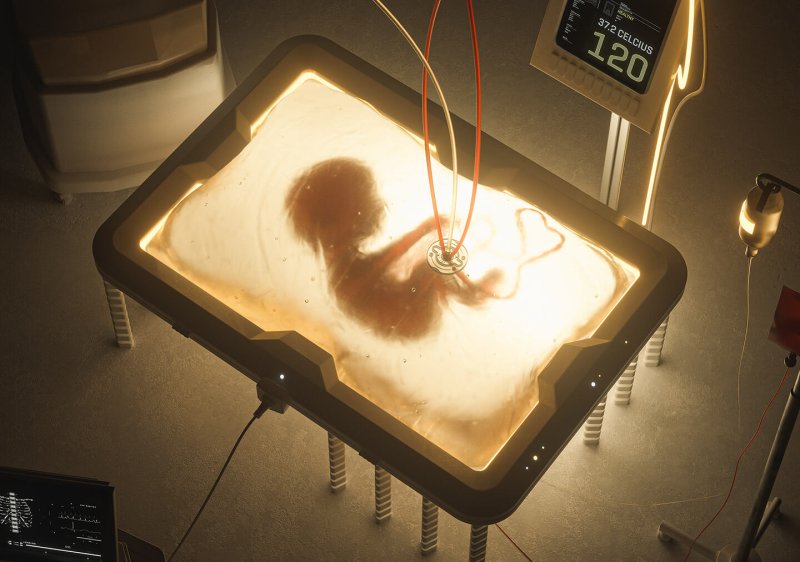

But a scientific breakthrough is on the horizon that could irrevocably alter the abortion debate as we know it. That breakthrough is the artificial uterus, which could drastically lower the developmental age at which an unborn baby is viable, potentially to as early as conception itself.

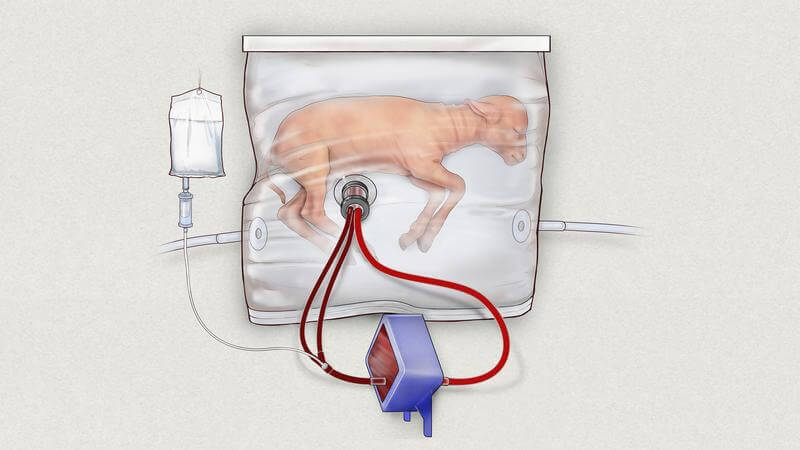

At present, an artificial uterus with the latter capability is firmly in the realm of science fiction and likely will remain that way for some time. However, artificial uteruses capable of shrinking the age of viability to 15 weeks may not be that far off. In 2017, scientists at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia detailed their artificial womb that permitted premature lambs roughly comparable to 22- to 24-week human fetuses to develop healthily. At the time, the lead researcher, fetal surgeon Alan Flake, expressed to NPR his hopes to test the womb on human fetuses within the next three to five years.

As artificial wombs arrive and push the age of fetal viability earlier and earlier, the debate over abortion will transition to one over “extraction.” Imagine a world where the developing embryo is viable immediately at conception. Under current laws, states could potentially prohibit mothers from killing the fetus and require them instead to undergo an extraction procedure to place it in an artificial womb until it is ready to survive outside as a fully-formed baby. The question then would be whether or not the state has the right to force a woman to undergo such a procedure, which could be both invasive and risky.

One could imagine another ethically fraught scenario. Currently, state agencies can remove children from negligent or abusive parents. With artificial wombs, could they also potentially mandate the removal of fetuses from pregnant women deemed not to be fulfilling standards of care during pregnancy – if the expecting mother is using drugs, alcohol, or tobacco, for example.

And, of course, in a world where terminating a pregnancy does not mean killing a fetus, we could see over 600,000 more babies born in the U.S. each year. Who will care for all of these potentially unwanted infants? Parents? States? Perhaps a mix, where parents of extracted babies are required to pay a tax so the state can care for them? In states with such monetary penalties, contraception rates would undoubtedly skyrocket. We might also see a thriving black market for present-day abortion procedures.

As I. Glenn Cohen, a professor at Harvard Law School and faculty director of the school’s Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics, wrote at Vox:

“Once we go beyond the burdens of gestation as the justification for abortion and instead turn to the psychological, financial, and social burdens of unwanted parenthood, the potential of adoption to reduce — but not completely eliminate — some of those burdens may become relevant.

While the invention of an artificial uterus for humans would end the abortion debate as we know it, the new controveries spawned will not be any easier to solve. That’s why Alan Flake, creator of the artificial uterus for lambs, has no desire to test the limits of his revolutionary procedure.

“I want to make this very clear: We have no intention and we’ve never had any intention with this technology of extending the limits of viability further back. I think when you do that you open a whole new can of worms,” he told NPR.

Steven “Ross” Pomeroy is Chief Editor of RealClearScience. A zoologist and conservation biologist by training, Ross has nurtured a passion for journalism and writing his entire life. Ross weaves his insatiable curiosity and passion for science into regular posts and articles on RealClearScience’s Newton Blog. Additionally, his work has appeared in Science Now and Scientific American. Follow him on Twitter @SteRoPo

A version of this article was originally posted at Real Clear Science and has been reposted here with permission. Real Clear Science can be found on Twitter @RCScience