Perhaps it is because the plan is legally infirm and/or has serious scientific and social deficiencies? Let’s investigate why this proposal is scientifically invalid and legally doomed from the outset.

Why people develop nicotine addictions

First, we should acknowledge that the cause of nicotine (or indeed, any) addiction is not completely understood. Nicotine addiction is both environmentally and genetically influenced, with our genes playing a very significant role in addiction development. A meta-analysis more than a decade ago found that genetic factors drive more than half of all addictions in women, and about a third in men, yet Biden’s proposal doesn’t address the genetic determinants.

The administration’s grand vision is the promise of a reduction of over eight million tobacco-related deaths — by the end of the century. Based on 2014 statistics, this is translatable to preventing 480,000 deaths per year (including 163,700 cancer-related deaths). This reduction is expected to be fairly immediate and dramatic — based on a form of “scientific” prophecy called “mathematical modeling”, which has historically produced some very erroneous results, along with bad policy.

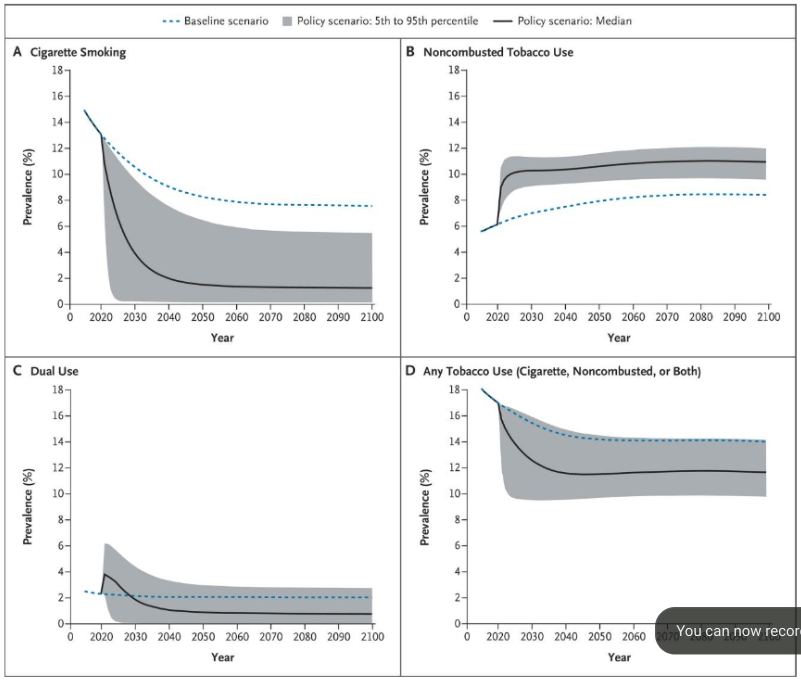

Yet, regarding “operation moonshot”, a 2018 New England Journal of Medicine study makes it clear that mathematical modeling is the driving force behind the initiative:

Simulation models can be used to project the potential population-level effects of regulatory actions…. Our model indicates that enacting a regulation to lower the nicotine content of cigarettes to minimally addictive levels in the United States would lead to a substantial reduction in tobacco-related mortality, despite uncertainty about the precise magnitude of the effects on smoking behaviors.

Here’s the problem: As the 2018 report illustrates, these claims, “validated” in beautiful mathematical models and pretty graphs, over-simplify the inquiry by modeling just two parameters: imposed reduction of nicotine to some “magic”, unspecified amount, and an assumed universal compliance. The level of this ‘magic’ threshold dose — a scientific conundrum — is not specified in the models.

So, here’s the rub: The success of Biden’s initiative is entirely dependent on determining this effective threshold level. Yet, we don’t know what that level is — or indeed if any legally allowed level that would successfully prevent addiction exists.

How nicotine works on the body

Nicotine, itself, is not a carcinogen, but rather an addictive compound that exposes the smoker to carcinogens via the smoke delivering the puff. The theory goes that if nicotine is reduced to non-addictive levels, people would automatically stop tobacco smoking. In other words, (and note the logical leap): if people don’t get addicted to nicotine, they won’t be exposed to the carcinogenic smoke, and we can expect the death-reduction tally to begin immediately after the anticipated regulation. This is an inaccurate and logically infirm postulate.

First infirmity: Third-hand smoking effects

Besides secondhand smoke, which presumably would be eliminated if everyone comports with the new laws (a big if), we can expect at least six months of residual exposure to noxious tobacco products remaining in room furnishings after cigarette cessation — something called third-hand effects. These exposures are not insignificant. So, the graphs are not accurate unless they are adjusted for that omission.

Another logical infirmity: The confused focus

The plan also seems schizophrenic or confused (or both) in its purpose. Who is its target audience? That same NEJM study referenced above claims it is designed to prevent new, younger smokers:

The majority of cigarette smokers in the United States began smoking during their youth …. The age at which people begin smoking can greatly influence how much they smoke per day and how long they smoke, which ultimately influences their risks of tobacco-related disease and death.

If the motivation behind the regulation is to prevent new, young smokers and hence future addiction, wouldn’t the objective be better served by raising the allowable age of smoking? Why allow young adults a whiff of the lure of nicotine — if you can prevent exposure entirely?

Nevertheless, the dramatic graphics supporting the initiative reflect the alluring ramifications when all current smokers quit, regardless of age. In a way, the administration’s project is akin to mandatory smoking cessation programs, which have been shown to be ineffective. As to why this approach is expected to work in this context — who knows?

The third logical infirmity: Legal invalidity and unanticipated consequences of a contraband market

While the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act confers on the FDA the power to regulate cigarettes, it isn’t allowed to ban them or reduce nicotine levels to zero. Further, public health effectiveness must be shown.

The FDA must consider scientific evidence regarding “the risks and benefits to the population as a whole, including users and nonusers of tobacco products,” along with “the increased or decreased likelihood that existing users of tobacco products will stop using such products” and “the increased or decreased likelihood that those who do not use tobacco products will start using such products.”

As to the public health impact, for most adults already addicted, it defies logic to believe that if their nicotine fix is not legally available, they won’t secure the product illegally — or load up on multiple sources of the drug from other nicotine-containing products to “treat” the cravings and compensate for other withdrawal effects.

The proposed solution: lower nicotine to non-addictive levels, which are hypothesized to be 0.5 mg per cigarette (approximately 0.7 mg per gram of tobacco) (Donny 2015), two orders of magnitude less than current branded cigarettes, i.e., to set a threshold allowable limit of non-addictive levels such that this won’t be possible to compensate by layering products.

This approach feeds the legal argument that reducing the defining ingredient of cigarettes, i.e., nicotine, to minuscule levels de facto bans cigarettes, which the FDA is not allowed to do.

Another concern is the fear that the addicted will turn to illicit or contraband sources if the nicotine content was not high enough. Indeed, this fear has been recognized by the FDA. The issue of contraband or illicit consumption to cover nicotine-short-fall was addressed in a 24-page 2018 FDA monograph. But the monograph focused on availability of contraband cigarettes, not the behavior of the addicts.

Resort to criminal behavior as is prevalent when addicts are denied their fix (to wit: heroin, opioids such as fentanyl), itself a public health hazard, was not discussed. Such anticipated criminal activity carries its own public health and safety concerns, which the FDA will need to address before any regulation can be implemented.

Fourth infirmity: Proposed regulations aren’t science-based

While the cited model asserts a dramatic impact from the initiative from reduced deaths, it turns on an unspecified level to achieve these goals. So, is there such a level, and if so, what would its level be?

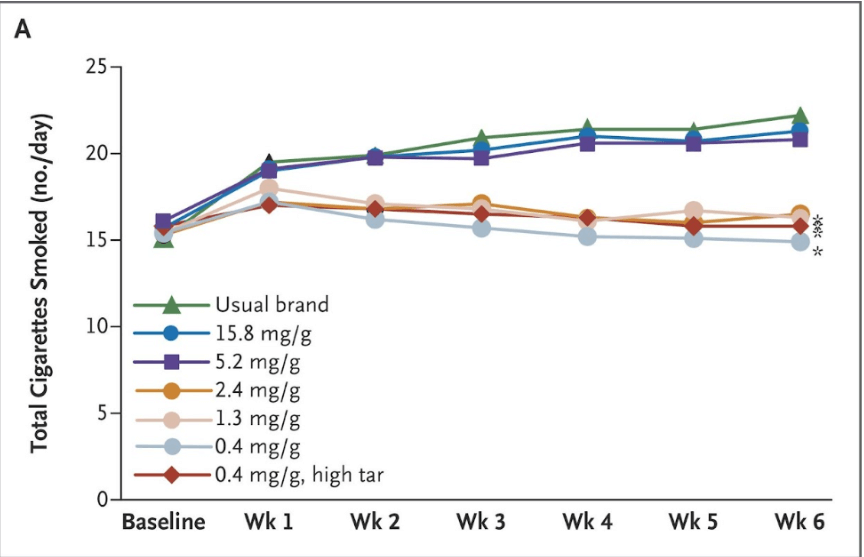

Some researchers have examined the question. One 2015 study in the New England Journal of Medicine (the only large-scale study at that time assessing less than 130 participants in each exposure group) evaluated the impact of five levels of nicotine exposure. While current proposals are based on this study, it has serious limitations, among them that it was a short-term study of six weeks. The study did refer to a longer-term study then in progress. Seven years later the results of that longer study have not been posted.

The 2015 NEJM short-term study- data, results, and accompanying graphical representations are curious:

During week 6, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day was lower for participants randomly assigned to cigarettes containing 2.4, 1.3, or 0.4 mg of nicotine per gram of tobacco (16.5, 16.3, and 14.9 cigarettes, respectively) than for participants randomly assigned to their usual brand or to cigarettes containing 15.8 mg per gram (22.2 and 21.3 cigarettes, respectively; P<0.001)

If validated, this study provides an impressive and statistically significant finding: a daily reduction of 5-7 cigarettes between the higher and lower nicotine exposure groups (levels above and below 5.2 mg/g of nicotine exposure).

But is this a valid interpretation of the study?

The actual data present a different picture. Those in the lower exposure categories smoked the same number of cigarettes after six weeks as they did at the start of the experiment (i.e., at baseline) — about 15 a day. Consumption of lower nicotine levels during the six weeks of the study made virtually no difference in their cigarette consumption. But participants in higher exposure groups (including those smoking cigarettes with their normal levels of nicotine or higher) increased cigarette consumption! They, too, started out at about 15 cigarettes a day. Only when comparing the two groups with each other do you find a significant difference, but not when comparing each group to itself at the start of the experiment (or baseline).

So, why did the higher-level exposure level groups increase cigarette consumption? The researchers attributed this finding to the free cigarettes dispensed, which apparently were more alluring only when the nicotine levels were high.

Thus, the “dramatic” difference attributed to lower-level nicotine exposure seems to be an artifact of the study design. In other words, it’s not that the lower exposure group smoked fewer cigarettes, but rather, those using their own cigarettes or given higher nicotine level cigarettes smoked more cigarettes than they did at the study’s inception. Further, the finding of lower cigarette (and hence nicotine) consumption was based on self-reporting, which is notoriously unreliable in consumption studies.

The objective biomarker data also reflect problems with the study’s claims. While total nicotine decreased in the two highest exposure categories, carbon monoxide levels, a surrogate for cigarette smoke, was not statistically different among the groups, nor was urinary NNAL, a chemical byproduct of tobacco consumption found in the urine of smokers. The analysis reports:

NNAL levels did not significantly differ according to the nicotine content of the study cigarettes…. [Further] the weekly expired carbon monoxide levels [a surrogate for smoke exposure] was [also] not reduced in parallel with the number of cigarettes smoked per day ….

This suggests either that the lower nicotine cigarettes did not significantly impact cigarette smoke exposure, and/or that study participants in the lower exposure groups went AWOL and found other means of compensating for their reduced nicotine fix.

Genetic illiteracy

So, what do we make of the overall Biden proposal? Let’s begin by acknowledging that nicotine is addictive and that the proposed laws are targeted at “addicts.” Would the administration’s intervention strategy likely work?

Removing the addictive substance, as the legislation purports to do, would not automatically cure them of their affliction. Indeed, even the 2015 NEJM article acknowledged that public health improvements from a reduction of nicotine content in cigarettes need to be “combined with other tobacco-control policies, e.g., taxation and afforded access to treatment)”, considerations absent in the Biden initiative.

Here is another unaddressed, yet critical issue: How do we set effective minimal exposure limits for nicotine, given that scientific evidence suggests that individuals respond so differently, influenced by an individual’s genetic makeup.

Rather than concocting policy based on simplistic correlative graphs or subjectively-reported research, we need a far more nuanced understanding of cigarette addiction.

What should the Biden Administration consider doing?

Understanding the genetic component is a key to resolving the conundrum. I would suggest that the government should begin by recognizing that cigarette smoking is not a single-step activity, and hence requires a multi-pronged analysis before providing a solution. A critical consideration in resolving these legal and scientific concerns is assessing the genetic components of cigarette addiction.

According to an oft-cited Nature Communications study from 2020:

Cigarette smoking is a multi-stage process consisting of initiation, regular smoking, nicotine dependence (ND), and cessation. Each step has a strong genetic component…

Hundreds of genetic factors are associated with the process of addiction, which begins when (and if) one starts smoking, and includes the age at initiation, the number of cigarettes one habitually consumes daily, whether one is inclined to quit, and whether one is successful. As to the threshold that determines “addiction,” that, too, is genetically influenced, although our understanding of which genes are involved here is comparatively paltry.

To craft regulatory policy designed to prevent addiction, understanding how this behavior is genetically influenced is critical. A proper inquiry would include understanding factors governing withdrawal severity, response to treatment, and other health effects. Without these data, the FDA cannot assess the public health impact of nicotine limits, and, in turn, cannot legally set nicotine limits.

The sheer number of genes involved and the variety of genetic influences tell us that there is great variance in individual responses to both nicotine dependence and initiation. These influences are more complicated than a graph modeling the reduction of deaths only against the number of cigarettes someone smokes and the time since they stopped smoking.

Moreover, an individual’s response to nicotine and to nicotine cessation is impacted by nicotine’s pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: including how long it takes for the nicotine to have an effect, to detoxify or metabolize, and the type of effects it has on the body — all of which are dependent on the individual’s genetic makeup. In sum, an individual’s genetic makeup dictates how nicotine breaks down, how long it takes, and how it affects the body.

We also know that nicotine affects cognitive function, including attention, learning, and memory. It may be possible to address nicotine-withdrawal effects on these factors by drugs other than nicotine. Such information would be useful in designing alternatives to nicotine reduction in cigarettes to achieve the same goal.

Setting rational policy

The proposed solution to curtailing cigarette smoking in those already addicted — minimizing nicotine levels — without any idea what those levels should be — may be futile. Worse, it could be dangerous.

Should we just then do nothing to corral nicotine addiction? Of course not. Prevention of the initial step in the nicotine-dependence chain is relatively straightforward: We could raise the permitted smoking age, which would be effective if it were seriously enforced.

The CDC has determined that 90% of smokers first began when they were less than 18; another 10% or so began between the years 18- and 26. While raising the permissible smoking age to 26 would be politically problematic, raising the age to 21 might be a more politically palatable solution and could significantly reduce the number of new smokers.

The key policy going forward: Let’s focus on changing the legal age of smoking and couple it with a serious enforcement program. We wouldn’t even need to figure out the legally allowable levels for nicotine in cigarettes or even the threshold for nicotine addiction.

Why don’t we just start there?

Barbara Pfeffer Billauer, JD MA Ph.D., is a Research Professor at the Institute of World Politics in Washington DC and a Professor in the International Program in Bioethics at the University of Porto and writes about the intersection of law, science, bioethics and religion.