This vaccine, which will be rolled out starting in 2022 is urgently needed. But it may not be enough. Despite this high-profile success story, now is not the time to relax. Instead, we urgently need to put more work and more money into the fight against malaria.

This vaccine, which will be rolled out starting in 2022 is urgently needed. But it may not be enough. Despite this high-profile success story, now is not the time to relax. Instead, we urgently need to put more work and more money into the fight against malaria.

With the Covid pandemic now in its third year, it is perhaps hard for the media and the public to switch focus to a different disease. But malaria is a huge killer. It ranks in the top three causes of death among children globally; nearly half a million children died of malaria in 2020.

As a malaria physician-scientist, I have spent over 15 years investigating the disease; before that, I lived and worked for three years as a US Peace Corps volunteer in a village in malaria-endemic Benin, West Africa. I have seen firsthand how millions of people are affected by this devastating disease.

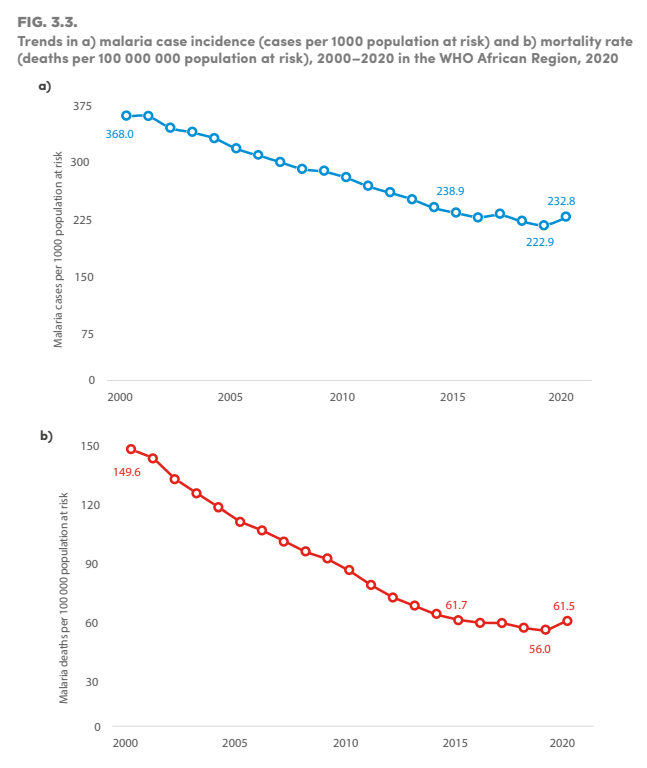

There were some early successes in battling malaria from 2000 to 2015. But we are now losing hard-won progress in the war. Mosquitoes have become resistant to insecticides; the malaria parasite has once again become resistant to commonly used drugs. Malaria deaths went up 12 percent from 2019 to 2020, topping 600,000 per year.

This vaccine comes at a critical moment, and may provide the fresh new weapon we need to crack the stalemate. Or it may not. We don’t yet know. The newly approved RTS,S vaccine has been tested and proved safe in hundreds of thousands of children, but very rare negative side effects may become apparent in a wider rollout. It is moderately effective, which is amazing, but not as good as it could be. Multiple booster doses may be required; the malaria parasite may evolve to evade it.

And so, though it may seem counterintuitive to policy makers and funders, now is the time to double down on research efforts to develop a second generation of vaccines that work better and perhaps differently, giving us options and new tools to defeat this global scourge. While there is good work going on, there could be much more. The total funding for malaria research and development has been declining since 2018; global vaccine funding in 2021 was disappointingly at its lowest since 2010.

Malaria vaccine development has a long history, and it wasn’t always clear that it could work at all. Unlike people with, say, measles, people who get malaria can recover and get it again; their immune system only learns a little about how to fight it off. This makes it hard to create a vaccine.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, researchers subjected mice and then people to thousands of bites from radiation-weakened mosquitoes and showed that this protected them against later exposure to malaria. They tracked this protection down to antibodies against the malaria parasite’s main surface protein, called circumsporozoite protein (CSP). Researchers couldn’t squeeze the entire CSP protein into a vaccine, so they spent years trying out different fragments until a front-runner emerged. They then mixed this protein subunit with a carrier — an antigen against hepatitis B — and an adjuvant to enhance the immune response. It worked. RTS,S was born in 1987.

The process for proving the safety and effectiveness of RTS,S was necessarily long. The first trials, with adults, were in 1995; it took dozens more across different countries and populations, including infants, to put it through all the paces. The RTS,S vaccine was finally brought across the finish line thanks to a public-private partnership (between GlaxoSmithKline and the nonprofit PATH’s Malaria Vaccine Initiative, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation). In the target population of children 5 to 17 months old, the vaccine has been shown to be around 56 percent effective for about a year. Models predict that rolling out the vaccine would be highly cost effective, saving hundreds of lives per 100,000 children vaccinated.

In December 2021, the private-public partnership Gavi approved funding to support rollout in sub-Saharan Africa. Currently, individual countries are figuring out their individual plans for RTS,S, with the earliest introductions expected later this year. People seem to be welcoming these vaccines with open arms, even in sub-Saharan African countries where there is some hesitancy against Covid-19 vaccines.

This is a wonderful success, but the war against malaria still has a long way to go. There will still need to be education campaigns to make sure the malaria vaccine rollout goes smoothly. And people still need to take all other sensible precautions, from sleeping under bed nets to draining the standing water that serves as a breeding ground for mosquitoes. Meanwhile, other advances in malaria vaccines are also providing promise and hope, including recent studies of the R21 vaccine, which has been trialed in children in Burkina Faso. It looks set to provide a higher protection — 74 percent to 77 percent for six months after vaccination. And there are candidate mRNA vaccines that piggyback on the recent wild successes of Covid-19 vaccines, which have already been trialed in infants as young as six months. Intensive and focused research to improve RTS,S could also quickly yield a better vaccine.

The good news is that new vaccines may be approved more quickly than RTS,S, both because the malaria vaccine approval process has been streamlined and because of the success in deploying Covid-19 vaccines so quickly. The bad news is that there isn’t enough money going into the cause. Funding for malaria vaccine development actually dropped by $21 million, or 15 percent, in 2020.

This first vaccine against malaria is a breakthrough, but not the only breakthrough we need. While we should celebrate this milestone, the time to advance next-generation vaccines is now.

Matthew Laurens is a professor of pediatrics and medicine and a pediatric infectious disease specialist who studies malaria at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health in Baltimore.

A version of this article was posted at Knowable and is used here with permission. Sign up Knowable’s newsletter here. Check out Knowable on Twitter @KnowableMag