But what constitutes a bad decision? As a recent congressional investigation reveals, that depends.

House Dems fault FDA’s ‘atypical’ review process for Biogen’s Alzheimer’s drug

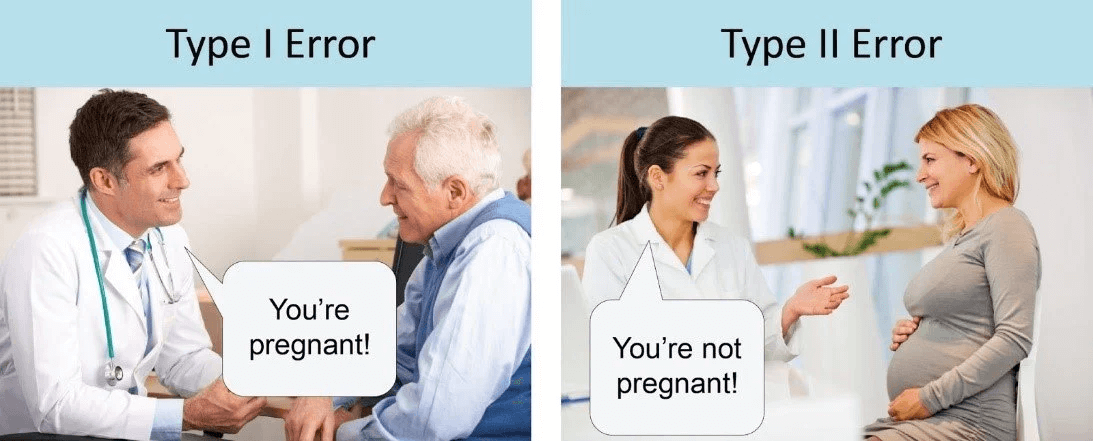

Regulators can err by permitting something bad to happen (approving a harmful product, a Type I error) or by preventing something good from becoming available (delaying or failing to approve a beneficial product, a Type II error). The two types of errors are opposing sides of the same coin: Too‐assiduous reduction of the incidence of Type I errors typically results in an increase in the incidence of Type II errors.

Both outcomes are bad for the public, but the consequences for the regulator are very different. Type I errors are highly visible and have immediate consequences: The developers of the product and the regulators who allowed it to be marketed are excoriated and punished in such modern‐day pillories as congressional hearings, news shows, and newspaper editorials.

A Type II error, by contrast, is almost always a non-event. Not surprisingly, then, regulators often make decisions defensively — in other words, to avoid Type I errors at any cost.

That is why the recently released results of an investigation by two House of Representatives committees into the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of Aduhelm, a drug to treat Alzheimer’s disease, are perplexing. It found that despite significant uncertainty about whether the expensive drug worked to slow or reverse patients’ symptoms, the FDA’s process for approving it was “rife with irregularities.” It concluded that the agency’s actions “raise serious concerns about FDA’s lapses in protocol.”

The report illustrates that the FDA is having problems threading the needle between Type I and Type II errors. As a longtime veteran of the agency and the author of a favorably received book about it, I can bring some insight into the issue. Here’s the bottom line: The FDA is not following the science.

I spent 15 years as the FDA’s “biotechnology czar” at a time when many of the biopharmaceutical companies were small startups needing guidance as they negotiated the regulatory maze. However, the agency’s recent involvement with biotechnology company Biogen, the manufacturer of Aduhelm, went far beyond “guidance” and was highly unusual in many ways.

At the FDA’s urging, the drug was resurrected three months after the company had canceled clinical trials because the drug appeared not to work. Subsequent developments over the next year were marked by at least 115 meetings, calls, and email exchanges between the company and the FDA, according to the report from the Oversight and Reform and Energy and Commerce committees.

Regulators assumed a major role in rebooting the company’s narrative and the effort to get the drug approved, even though there were substantial reservations about the effectiveness of the drug among several factions within the FDA, especially its statisticians, and even within Biogen.

Significantly, there was also strong opposition to the approval from the FDA’s external advisory committee. One critical concern was whether the endpoint of the clinical trials was meaningful. The justification for accelerated approval was that in Alzheimer’s patients, Aduhelm targets and reduces the levels of a protein, amyloid, that forms plaques — abnormal clumps of protein that collect within the brain. But there were no conclusive data showing that a reduction of amyloid slowed cognitive decline, the ultimate goal of any treatment.

If the drug doesn’t actually improve the dreaded symptoms of the disease, what good is it?

Another anomaly was that when the FDA granted “accelerated approval,” which requires a post-approval confirmatory trial, regulators gave Biogen an unprecedented eight years to complete it. During that time, the drug could be prescribed to the nation’s 6.5 million Alzheimer’s patients.

Finally, the approval granted was for all Alzheimer’s patients, although Aduhelm had only been tested in patients with mild-to-moderate disease. That raised the possibility that the drug would be administered to many people in whom it would not work, an important consideration given that Biogen intended to charge $56,000 per year per patient. That is several times more than other Alzheimer’s drugs, and it would be a huge hit to Medicare’s piggy bank — more than $300 billion a year for a possibly worthless drug!

What’s behind this dysfunction? It could be that a few high-ranking FDA officials have a personal obsession with treating Alzheimer’s disease that caused them to ignore the evidence and push the approval. Whatever the reason, I suspect we haven’t heard the last of the Aduhelm saga.

Henry I. Miller, a physician and molecular biologist, is the Glenn Swogger distinguished fellow at the American Council on Science and Health. A 15-year veteran of the FDA, he was the founding director of its Office of Biotechnology. Find Henry on Twitter @henryimiller

A version of this article was originally posted at the Washington Examiner and has been reposted here with permission. The Washington Examiner can be found on Twitter @dcexaminer