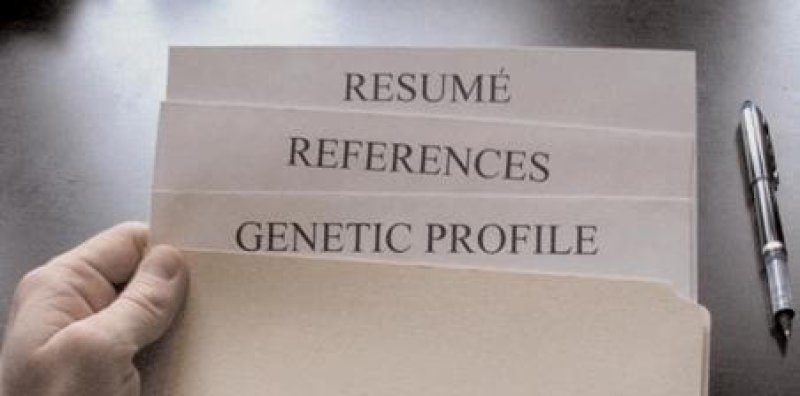

In 2008, the United States Congress passed the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) preventing the use of genetic information in health insurance and employment. And now Canada might soon be joining a handful of countries that have laws against genetic discrimination.

The bill, which makes it illegal to ask that someone disclose genetic information or undergo a genetic test in order to provide services such as insurance or enter into any kind of contract, was first introduced in 2013. Exceptions are made for medical or research purposes with patient consent. The bill also introduces amendments to labor and human rights acts making employment decisions based on genetic characteristics a criminal offence. Reports of bipartisan support are indicating that the passing of the bill into law is imminent.

When the human genome project began, the ethical, legal and social implications of such an initiative were a major concern. A little more than a decade after the human genome was sequenced; it is worthwhile examining what the global stance is on laws that regulate the use of genetic information as it pertains to insurance and employment.

Apart from the United States, only a handful of developed countries, most of them in Western Europe have passed laws pertaining to genetic information. A comprehensive review published in the Journal of Community Genetics indicates that as of 2012,

Five countries have enacted genetic specific laws, and three have comprehensive provisions pertaining genetic testing in their biomedical legislation. Central provisions cover informed consent, autonomy and integrity of the person tested, further uses of tests results, quality requirements of the personnel and facilities involved.

The United Kingdom has taken a slightly different approach, with a voluntary moratorium (set to expire in 2017) being signed between the government and the insurance industry that prevents the use of genetic test results to provide or alter health insurance. It is worthwhile noting that the United States is the only country where private health insurance linked to employment is the dominant adoption model, making the law a lot more relevant.

While most countries that have passed or are considering genetic discrimination laws include health insurance and employment under its purview, a clear divide is emerging, as to how these laws are being applied to life or long-term care insurance which may be exposed to significant risk. Countries like the US, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and UK allow genetic information to be used in risk assessment for high value insurance purchases such as life insurance. In contrast Austria, France and Portugal have excluded the use of such information in all types of insurance. In an article earlier this year, GLP contributor Meredith Knight discussed this issue as it pertains to the US version of the law, suggesting that advances in healthcare will make hereditary information less valuable.

As for the Canadian bill, in its current form, is quite broad in its scope and does not exclude life or long term insurance. Yann Joly, a geneticist at McGill University suggests that it is too early to make sweeping changes to Canadian law.

Deciding on the scope of anti-discrimination legislation (i.e. defining what constitutes genetic discrimination) would be a major challenge given the fast rate of scientific progress and the fact that most medical conditions have genetic components – as demonstrated by existing laws in other countries. Even with a Canadian law in place, insurers could find other ways of reaching their objectives through asking rigorous questions about familial history of diseases of applicants.

We are only beginning to see the tip of the iceberg as it pertains to tackling the legal concerns surrounding this issue. In countries that do have laws regulating the use of genetic information, there is too little data to indicate whether they are proving to be useful or not. This is most likely because genetic testing is still confined to a small percentage of the population, despite the attention it gets in medical and science media. As the costs of implementation come down and testing becomes more widespread, we will have to grapple with the strengths and weaknesses of existing legislation in a world of ubiquitous genetic data.

Arvind Suresh is a science communicator and a former laboratory biologist. Follow him @suresh_arvind

Additional Resources

- GINA’s sixth birthday: Does legislation protecting our genetic information mean anything?, Genetic Literacy Project

- Canada seeks to keep genetic data private from health insurers, Genetic Literacy Project

- I’ll Show You My Genome. Will You Show Me Yours?, Reason.com