Those genetic data can be anywhere. Is a pharmaceutical company looking at them? An insurance company, perhaps? How many people have seen your genetic data online? In short, just how private are those data?

Your immediate reaction might be something like “What?! My genetic data are not posted online!” That’s still true for most people, but if you’ve been a medical subject for any study using DNA information, or, if you’ve submitted DNA samples to one of those companies that tracks down your genetic lineage and finds long lost relatives, your genetic data are most surely on the web, somewhere. Genetic technology and information databases have been expanding at a staggering rate, but critics say that safeguarding genetic privacy has not kept up an appropriate pace.

Finding out whether you or a family member carries a disease gene —BRCA1 or BRCA2 for breast and ovarian cancer, for instance– can save lives, since the diseases are highly curable when detected early, and deadly when discovered late. Furthermore, somebody known to be at high risk due to a BRCA gene can be given preventive therapy. At the same time, learning of one’s true genetic heritage through comparative genomic analysis can be not only fascinating, but change one’s perspective on life.

Genetic family search data are on the web

By looking at the regional ancestry reference populations posted by National Geographic, you can make an educated guess about your genetic ancestry, based on the national population from which you come. However, you get get ancestry information specific to you, which can include surprises, if you send a sample of your DNA to an ancestry company, such as 23andme. Imagine finding out that you’re 7 percent Mediterranean, 4 percent Amerindian, 18 percent southwest Asian, 20 percent northern European, and 9 percent African, when you thought you were just a white person from Irish and mainland Europe immigrants. Imagine a family descended from slaveholders in the American south learning that they’re also descended from African slaves, or a Palestinian learning his ancestry is partly Jewish.

But, in addition to telling you fascinating things about your ancestry, what does the company do with the data? The answers are both good and bad. On the good side, there is medical research. With all of those genetic data from thousands of individuals, 23andme can find out useful things, such as how common is a certain disease-causing gene, and how common is that gene in people with a certain genetic makeup? Beyond that, the test performed on your DNA can amount to a screening test for a plethora of diseases that you might develop, and knowing this can help you talk preemptive action. In fact, 23andme tries to use the data to recruit people at risk for various cancers and neurodegenerative, such as Parkinson disease, for research studies.

However, as one Scientific American blogger cautions:

One could easily imagine how insurance companies and pharmaceutical firms might be interested in getting their hands on your genetic information, the better to sell you products (or deny them to you)…Although 23andMe admits that it will share aggregate information about users genomes to third parties, it adamantly insists that it will not sell your personal genetic information without your explicit consent..Early signs certainly aren’t encouraging. Even though 23andMe currently asks permission to use your genetic information for scientific research, the company has explicitly stated that its database-sifting scientific work “does not constitute research on human subjects,” meaning that it is not subject to the rules and regulations that are supposed to protect experimental subjects’ privacy and welfare.

Thus, on the website 23andMe actually warns “Genetic Information that you share with others could be used against your interests.

Relatives sharing your data

Since you share genes with family members, the privacy issue is exacerbated when anyone related to you sends a sample to 23andme for analysis. You may be extremely cautious yourself, even deciding never to submit your own sample to such a company, and organizations like the Counsel for Responsible Genetics can advise you on tactics for keep your genetics private. But you can’t stop your siblings cousins, and other relatives from doing it. In fact, distant cousins whom you’ve never met can send their own samples, so their genomes enter a database; then pharmaceutical companies, insurance companies, or any interested party can connect that relative’s information with you.

Matching genome information with surnames: Not as hard as you may think

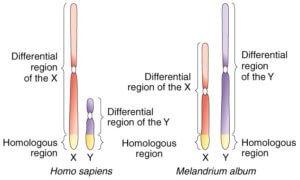

Of course, there have been calls for stricter rules on protecting genetic privacy, but the amount of genetic information online has skyrocketed in the last decade. So many genetic data are available from so many individuals that two years ago a team of researchers based in Boston, Houston, and Tel Aviv published a sobering paper in the journal Science showing how information obtained by searching “recreational genetic genealogy databases” (like those of 23andme) can be matched with surnames of those supplying the DNA. The tactic involves using certain genetic sequences from what’s called the differential region of Y chromosome, that part of the human genome that –like the surname– is passed only directly from father to son.

On top of this, the genetic information, while kept online separate from the identity of the person who supplied the sample, can be crosschecked with other types of metadata, such as ages and states of residence, to triangulate the identity of a certain person. As the senior author of the study, Yaniv Erlich, explains:

Our technique exploits this correlation to identify the surname of individuals and uses open genetic genealogy databases to infer the right surname. Surnames are strong identifiers. Correctly inferring them dramatically narrows the search space. We specifically showed that if the age and state of the targeted individual are known (HIPAA [Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996] does not protect these two identifiers), then a surname inference can virtually resolve the identity of the person.

While it may sound scary, and certainly highlights the difficulty of genetic privacy, we must remember that the reason we have the problem is because or capabilities have increased substantially. As an analogy, consider the power of nuclear technology, but along with it the fact that being so powerful it also comes with great risks.

So, when asked, two years after his paper in Science, whether the finding should be taken to mean that we should avoid supplying our genetic data, Erlich suggests that the answer is no, given the potential of DNA information to improve medicine.

“We are all going to be sick in some point of our life,” Erlich notes. “The people that we love the most are going to be sick….Medicine will not be able to take advantage of the genetic revolution without massive collection of DNA information from healthy and sick individuals and exchange this information between researchers and clinicians.

That’s a good reason for people to continue sending their samples to build up the genetic databases. On the other hand, says Erlich, “This is why it is so important to map those privacy issues, plan the right safeguards, and explain the risk and benefits (and there are many benefits) for our research participants.”

David Warmflash is an astrobiologist, physician and science writer. Follow @CosmicEvolution to read what he is saying on Twitter.