Tinted, semi-transparent solar panels can generate electricity and simultaneously produce nutritionally-superior crops, offering farmers the prospect of higher incomes and maximizing their land use.

By allowing farmers to diversify their portfolio, this novel system could offer financial protection from fluctuations in market prices or changes in demand and mitigate risks associated with an unreliable climate, a new study suggests. On a larger scale it could vastly increase capacity for solar-powered electricity generation without compromising agricultural production.

“With so many crops currently grown under transparent covers of some sort, there is no loss of land to the extra energy production using tinted solar panels,” said Dr. Elinor Thompson of the University of Greenwich and lead author of the study.

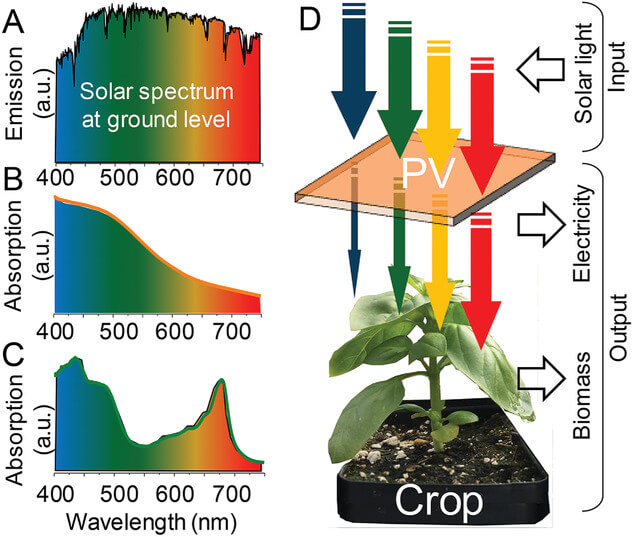

This is not the first time that crops and electricity have been produced simultaneously using semi-transparent solar panels — a technique called “agrivoltaics.” But in a novel adaptation, the researchers used orange-tinted panels to make best use of the wavelengths — or colors — of light that could pass through them.

The tinted solar panels absorb blue and green wavelengths to generate electricity. Orange and red wavelengths pass through, allowing plants underneath to grow. While the crop receives less than half the total amount of light it would get if grown in a standard agricultural system, the colors passing through the panels are the ones most suitable for its growth.

“For high value crops like basil, the value of the electricity generated just compensates for the loss in biomass production caused by the tinted solar panels,” said Dr. Paolo Bombelli, a researcher in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Biochemistry, who led the study. “But when the value of the crop was lower, like spinach, there was a significant financial advantage to this novel agrivoltaic technique.”

The combined value of the spinach and electricity produced using the tinted agrivoltaic system was 35 percent higher than growing spinach alone under normal growing conditions. By contrast, the gross financial gain for basil grown in this way was only 2.5 percent. The calculations used current market prices: basil sells for around five times more than spinach. The value of the electricity produced was calculated by assuming it would be sold to the Italian national grid, where the study was conducted.

“Our calculations are a fairly conservative estimate of the overall financial value of this system. In reality if a farmer were buying electricity from the national grid to run their premises then the benefit would be much greater,” said Prof. Christopher Howe in the University of Cambridge’s Department of Biochemistry, who was also involved in the research.

The study found the salable yield of basil grown under the tinted solar panels reduced by 15 percent, and spinach reduced by around 26 percent, compared to normal growing conditions. However, the spinach roots grew far less than their stems and leaves: with less light available, the plants were putting their energy into growing their “biological solar panels” to capture the light.

Laboratory analysis of the spinach and basil leaves grown under the panels revealed both had a higher concentration of protein. The researchers think the plants could be producing extra protein to boost their ability to photosynthesize under reduced light conditions. In an additional adaptation to the reduced light, longer stems produced by spinach could make harvesting easier by lifting the leaves further from the soil.

“From a farmer’s perspective, it’s beneficial if your leafy greens grow larger leaves — this is the edible part of the plant that can be sold.” Bombelli said. “And as global demand for protein continues to grow, techniques that can increase the amount of protein from plant crops will also be very beneficial.”

All green plants use the process of photosynthesis to convert light from the sun into chemical energy that fuels their growth. The experiments were carried out in Italy using two trial crops. Spinach (Spinacia oleracea) represented a winter season crop: it can grow with fewer daylight hours and can tolerate colder weather. Basil (Ocimum basilicum) represented a summer season crop, requiring lots of light and higher temperatures.

The researchers are currently discussing further trials of the system to understand how well it would work for other crops, and how growth under predominantly red and orange light affects the crops at the molecular level.

This article was originally published at Cornell Alliance for Science and has been republished here with permission. Follow the Alliance on Twitter @ScienceAlly