The last category usually has received the shortest shrift.

For both the herbicide glyphosate and the fungicide copper sulfate, the EU granted a five-year license. But there the similarity of how Europe handled them ends.

Glyphosate wars

In August 2018, the EU took up the reauthorization for farmers and homeowners to use glyphosate, an herbicide that was better known in its patented days as part of Roundup. The pesticide has served as an effective eradicator of weeds (or any other plant it touches), but has been equally effective as a target for anti-GMO, “Green” political activists who point to its popularity in removing weeds around crops like corn and soy that were genetically engineered to resist it.

The EU came to its decision after years of wrangling going back to 2002, with member countries, green members of the European Parliament, and activist groups. Glyphosate is authorized for use in the EU until December 2022, but anti-pesticide groups continue to push for an outright ban of the herbicide.

So far, only the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the cancer research arm of WHO that has come under criticism for bias on certain chemicals, has connected glyphosate to cancer in humans. In 2015, IARC declared glyphosate a Class 2a hazard, putting it in the “probably carcinogenic to humans” category. However, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the European Commission and other health and environmental agencies have declared it safe as used, and it’s licensed in 130 countries.

Copper sulfate tack

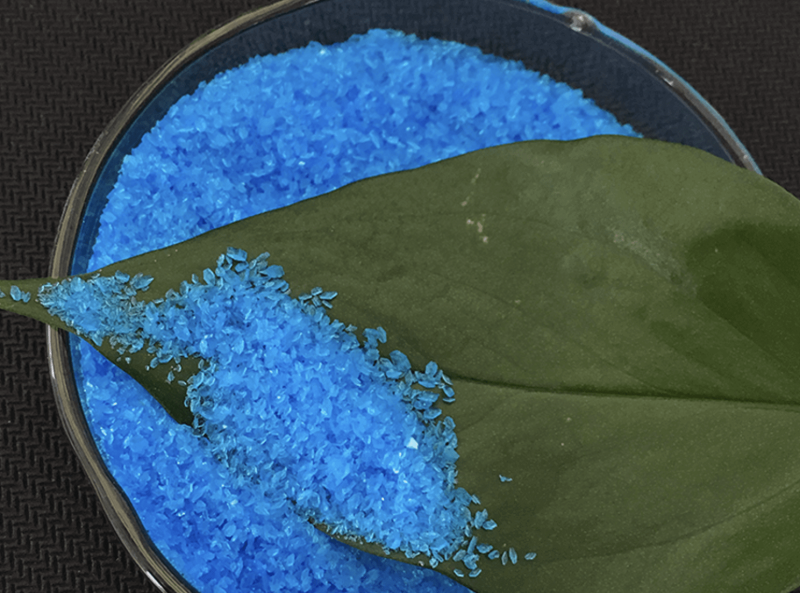

Later, the authorization for copper sulfate, a fungicide considered the only realistic antifungal tool that organic farmers are permitted to use, appeared at first to have a far easier pathway from the EU and member countries.

The European Union executive proposed renewing the license for copper sulfate and other copper compounds for five years. This proposal came after a one-year extension approved in December 2017 that allowed food regulators to analyze the latest science. The proposal was delayed again with no clear deadline, but the EU made a decision by year-end 2018.

In January 2018, the French National Institute for Agricultural Research (INRA) in a report co-commissioned by the French Institute for Organic Farming (ITAB), concluded: “Excessive concentrations of copper have adverse effects on the growth and development of most plants, microbial communities and soil fauna,” recommending in a scientific report that the government should intervene to “reduce use of copper for the protection of biological uses”.

A few months later, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) declared copper compounds to be “of particular concern to public health and the environment.” The EFSA has concluded glyphosate poses no serious ecological or public health danger. Definitive research has shown copper sulfate can be toxic to humans, far more so than glyphosate. It is not as targeted as many biological pesticides are, so whatever it does to fungus cells, it can do to you and to beneficial insects. It has been associated with skin and eye irritation, and swallowing large volumes of it can cause nausea, vomiting and tissue damage.

It is toxic to honeybees and a study showed extreme toxicity to bees in tropical environments (it was carried out in Brazil), where copper sulfate is used as a sprayed fertilizer (to provide heavy metal nutrients). In addition, and unlike glyphosate, the European Chemicals Agency has declared it a carcinogen—research has associated it with kidney cancer, in particular. As a carcinogen, copper sulfate would be subject to EU regulations restricting its use among workers, if not banned altogether.

Also unlike glyphosate, copper compounds are slated to be phased out over time (even with EU approval), and possibly replaced with less toxic fungicides.

And that’s where another similarity between glyphosate and copper arises: alternatives (although at higher cost and less effectiveness) exist for both glyphosate and copper in conventional farming, but glyphosate isn’t allowed in organic farming, and copper sulfate is the only fungicide approved for organic farming. And no other reliable replacement for copper exists for organic agriculture. In fact, IFOAM, the Germany-based international organic lobbying organization, has been encouraging the EU to continue authorization for copper sulfate, while allowing for some flexibility on how many kilograms per year farmers can use, even though it’s potential harms to agricultural workers is readily acknowledged.

Copper matching less with wine

Because of the severe toxicity of copper sulfate and a growing movement to focus on sustainability rather than on growing techniques, several companies in the wine industry, a heavy user of copper sulfate for at least a century, have backed out of organic farming.

This past fall, the vice president of the professional association of Bordeaux wines predicted that his region and others in France would started converting from organic growing to conventional. The organization cited a number of economic, weather, as well as chemical factors, including hail storms, blight, and a freeze in 2017. Wineries, VP Bernard Farges said, decided that the added risks of continuing with organic farming and copper was too much.

EFSA’s damning report on copper sulfate puts green advocates in Europe in a bind. Eric Andrieu, an MEP from the Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D group) is the chief of the PEST committee created to monitor the transparency of pesticide authorization in the EU. Andrieu previously has insisted that public health should be prioritized against economic interests when it comes to pesticides’ authorization. But in the case of copper, he lobbied for policy-makers to show flexibility.

“Alternatives to copper remain very limited and currently do not meet the demand of 500 million consumers. In the short term, the survival of a large part of European winery, in particular, the organic winery is at stake ,” he told EURACTIV in June 2018.

The organic community has begun to divide over the issue, pitting sustainability advocates against organic purists who are committing to maintaining aging regulations even if they are harmful to the environment. Previously, Domaine de Fondrèche in Mazan, under the French appellation of Côtes de Ventoux, announced that it was withdrawing its organic certification, which it had been growing wines under since 2009. The winery cited copper buildup in its fields, the result of using copper sulfate.

For some wine growers and researchers, genetics may provide a solution to the pest problems. CRISPR/Cas9, has shown promise (at least in the lab) against copper sulfate, but the results are very preliminary.

Other winemakers have argued that the problem may not lie as much in regulations as in overly simplistic definitions that separate organic from conventional farming. “Natural is good, synthetic is bad? It’s too basic to reason that way,” Charles Philipponnat, CEO of Philipponnat Champagne, told Wine Spectator magazine. “The objective is to make fine wine in a way that doesn’t leave a negative impact for our children.”

A version of this article originally appeared on GLP on December 19, 2018.

Andrew Porterfield is a writer and editor, and has worked with numerous academic institutions, companies and non-profits in the life sciences. BIO. Follow him on Twitter @AMPorterfield