Aotearoa New Zealand, the Land of the Long White Cloud, is the first place to see the sunrise on a clear day. New Zealanders pride themselves on other firsts as well – the first country in the world to give women the vote (1893), implement social security for everyone (1938) and remove farm subsidies (mid-1980s).

The latest first: declaring the goal of being predator-free by 2050. It’s ambitious, but if successful it would build on previous success in pest eradication in New Zealand. The government is targeting possums, stoats and rats, with a goal of keeping the island continent atop of the world list in fighting invasive species.

The challenge is considerable and complex, not the least because New Zealand has adopted an ultra-precautious approach to the use of gene technologies, including gene editing. New gene-drive techniques could change public perceptions.

Gene drives and species removal

Gene drives involve deliberately spreading a faulty gene throughout pest mammalian or insect populations, turning their own genes on themselves so they can no longer reproduce. In a short period of time, their population collapses. They have been used successfully to eradicate malaria and Zika-carrying mosquitoes in field trials in Brazil, Cayman Islands, Panama and the United States.

Three Drosophila melanogaster fruit flies engineered to carry a gene drive. Credit: New York Times

Many animal conservationists are excited about the possibility of using gene drives to clear invasive species to allow native species to flourish, but the ethical, regulatory and biosecurity questions are still being debated and evaluated. Although some skeptics say that using CRISPR to gene edit mosquitoes or animal pests could result in unanticipated butterfly-effect like disruptions of the ecosystem, most scientists believe that gene drives could be effective and safely managed.

Predator removal strategies

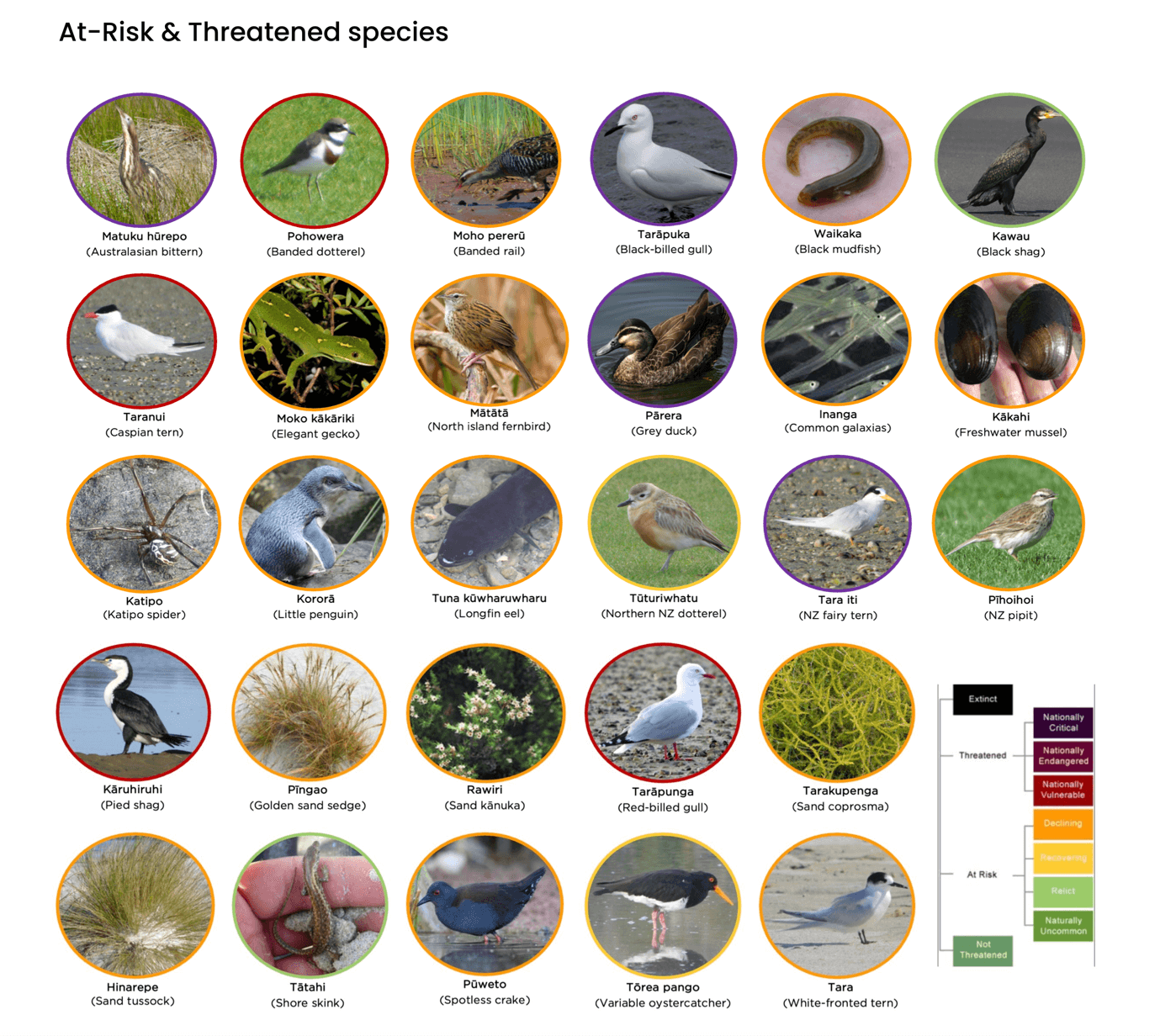

The broader predator-free government-led strategy arises out of New Zealand’s precarious experience in protecting native species, some of which — 60 birds, three frogs, seven vascular plants and an unknown number of invertebrates — have already been lost. The Department of Conservation (DoC) estimates that more than 3000 of the over 9000 native land species assessed are threatened with, or at risk of, extinction. Over 25 million native birds are thought to be killed by non-native predators each year.

To address the crisis, the DoC issued a strategy proposal with three main goals: 1) refine current predator control tools to make them safer and more cost-effective: 2) develop new or improved tools to eradicate predators at a landscape scale; and 3) expand predator control so that a range of tools are available for different environments and situations.

Hitting those marks won’t be easy. The problem is that New Zealand native birds, reptiles, bats and insects have not evolved to hide, escape or defend themselves from ground-based predation. New Zealand has no native mammals (apart from bats) and native species were unable to cope against the mammalian predators that arrived with Māori and European settlers. They introduced mustelids (stoats, ferrets and weasels), rats, possums and other predatory species such as cats, dogs, hedgehogs and mice — and these predators had (and are still having) a field day.

Another problem is the scale involved. The DoC estate covers nearly 30% of New Zealand, amounting to 80,000 square km. The last budget round increased funding, with an extra NZ$64m for delivery of the Predator Free 2050 Strategy and NZ$27m for maintaining the National Predator Control Programme levels, but funding is still woefully short of what is required. In 2020/21, NZ$10.8 million was spent on aerial 1080 poison operations, covering 3,420 square km, compared with NZ$17.3 million and 7,225 square km the previous year. Even in a good year, predator control occurred in less than 10% of the DoC area.

Aerial drops of poison are required because much of the New Zealand forest is difficult to access by foot. 1080 operations are considered suitable because 1080 works on mammalian pests and allows blanket coverage of areas.

Trapping is also considered important but is impractical in much of New Zealand’s forests. The number of traps needed and the trap lines that would have to be cut, walked regularly and maintained mean that trapping is restricted to a relatively small area. Nevertheless, in an attempt to reduce 1080 drops, DoC is investing NZ$1.4 million annually in new trapping tools and technologies. It is also calling on New Zealanders to get involved.

The Predator-Free by 2050 policy blueprint, which focusses on the mustelids, rats and possums, outlines a challenge that New Zealanders can face collectively. But current efforts and funding have so far proved insufficient. New lures, new ways of trapping and new ways of spotting pests are not having the necessary impact.

Facing thousands of endangered native species, and having identified seven predators (not counting dogs and cats), a game changer is needed, and welcomed by many conservationists. As the crisis has grown, the tide has begun to turn on the public and government’s view of the potential dangers and benefits of gene editing and other newer strategies to bring the chaos under control.

If New Zealand hopes to be the first country in the world to rid an ecosystem of introduced predators, it will take more than people working together — it will take embracing and implementing all available technologies. The development of new biotechnologies would seem to make sense, particularly gene editing and gene drives, which offer the chance to create a self-limiting population of unwanted species.

A survey conducted by the New Zealand company ResearchFirst in July was promising. It found that 62% of people would support the use of gene editing to protect taonga (highly prized) species such as manuka. Gene editing to treat human diseases achieved 66% support, slightly higher than for addressing taonga species survival, whereas gene editing for vaccines or medicines received 61% support.

Given the massive disruption that predators have created in the natural New Zealand ecosystems, the timing could be right to revisit the current regulations surrounding genetic modification … as other countries are doing. Considering the escalating ecological crisis, many scientists are pushing for a rethink.

“In applying gene editing to pest control, my sense is the public place greater emphasis on saving our taonga species, and so support tools that may achieve this, especially where they may reduce use of other methods such as toxins like 1080,” University of Auckland conservation biologist Professor James Russell said recently.

Utilizing this cutting-edge technology also could open other innovation doors.

In 2019, geneticist Professor Peter Dearden was part of a Royal Society Te Apārangi-appointed panel that reviewed the role gene-editing could be utilized to control pests. Now he sees broader applications.

“I think we need to move beyond growing animal proteins, and build a sustainable industry producing high quality protein from plants, algae and bacteria … and to do this well, we will need GM,” he says.

“The benefits in climate change, environmental footprint of food growth and exports will be huge,” he said recently.

The most significant impact could come to agriculture. Dr. John Caradus, Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand and the New Zealand Institute of Agricultural and Horticultural Science, and a pioneer in plant breeding, research, is urged in a recent peer-reviewed article for a revolutionary re-think of the country’s approach toward genetically modified and gene-edited crops.

It has been argued that opposition to gene technology has taken on a life of its own and provided little benefit to anyone, and that the ethics of agricultural and food biotechnology has been drowned out by simplistic arguments about feeding the world, on one side, and a blend of fearmongering and ignorance of food systems, on the other.

The development of new GM crops that provide either human health and nutritional benefits or assist with solving current and future environmental challenges will deliver consumer benefits

From a regulatory viewpoint, consideration is required to focus on regulating the benefit-risk issues associated with the end-products of genetic modification rather than the processes used in their development…

Genetic-based farming strategies are unsettling to those reluctant to embrace technological innovation even in cases in which the ecological rewards are enormous and the risks, while real, are minimal. But the native species of Aotearoa and New Zealand’s food and farming industry deserve them.

Dr. Jacqueline Rowarth, soil scientist and adjunct professor at Lincoln University, was the inaugural Chief Scientist for the New Zealand Environmental Protection Authority. She is now a farmer-elected director of DairyNZ and Ravensdown, and a producer-appointed director of Deer Industry NZ. [email protected]

Jon Entine is the founding executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project, and winner of 19 major journalism awards. He has written extensively in the popular and academic press on media ethics, corporate social responsibility, sustainability, and agricultural and population genetics. You can follow him on Twitter @JonEntine